Breadcrumb

- Our Work

- Discover California Seafood

- Seaweed Aquaculture

Seaweed Aquaculture

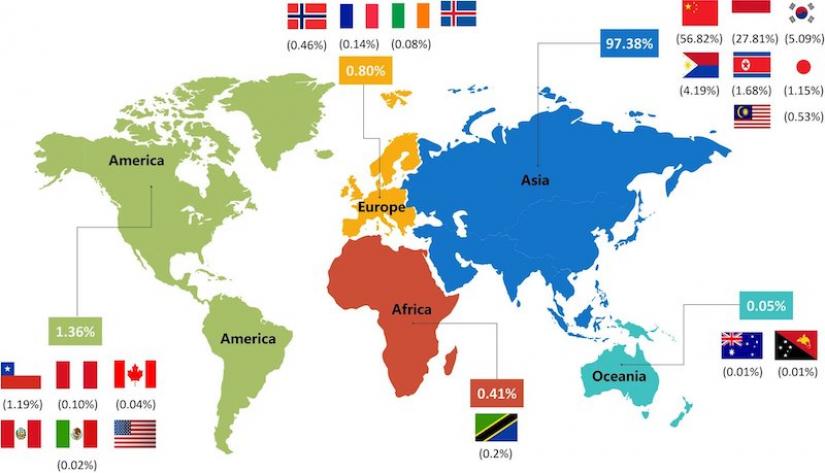

Most people know that seaweed appears in sushi rolls — but did you know that it’s in your toothpaste and your ice cream, too? The planet’s many species of aquatic macroalgae have countless uses, but so far the industry has been centered in Asia. Now, entrepreneurs are trying to bring seaweed aquaculture to California.

Here’s a breakdown of why that’s happening, how a seaweed farm operates and what it will take to get this industry off the ground.

What is driving interest in seaweed aquaculture?

The seaweed aquaculture industry is growing across the world, with global output increasing more than threefold between 2000 and 2019.[1] That’s in part due to the many potential applications of seaweed species, which are a source of nutritious food, medicines and cosmetics for humans, feedstock for animals, cosmetics, medicines and raw materials for industrial purposes. The U.S. government has also invested in efforts to explore seaweed’s potential as a biofuel source.

Really, though, the recent interest in seaweed is about more than its commercial applications. Seaweed is seen as one potential solution to pressing ecological and social challenges.

- Many seaweeds grow much more rapidly than terrestrial plants and do not require the use of freshwater and arable land, making them an appealing part of a solution to global concerns about food supply.

- Seaweed can help remove large quantities of dissolved nutrients that make their way from terrestrial sources and wind up polluting waterways.

- Seaweed removes carbon from both the ocean and the atmosphere as it grows — so if the crop is sunk into deep water rather than harvested, farmed seaweed offers a potential strategy for mitigating climate change.

With many consumers looking for sustainable choices, seaweed has become very marketable. So far, though, the United States has not been a big player in seaweed. Many entrepreneurs, seeing an opportunity, are seeking to increase production along California’s expansive coastline.

What is seaweed?

“Seaweed” is not a technical term, so you’ll find different definitions in different sources. Generally, the word refers to macroscopic, multicellular algae that live in watery environments. (This definition sets seaweed apart from tiny microalgae.) Increasingly, seaweed is referred to as “sea vegetables” in an attempt to better associate seaweed with something that people can eat.

Seaweeds are classified into phyla by color: green, red or brown. There are thousands of species of seaweeds, and hundreds with known commercial value, though only a handful are farmed.

What is the history of seaweed farming in California?

People began collecting and eating seaweeds in the Americas more than 14,000 years ago,[2] though in modern times, these species have become associated with Asian cuisines. Seaweed cultivation is a more recent phenomenon: as late as the 1950s, nearly all the world’s supply of seaweed was wild-collected.[1] In the 1960s, large-scale commercial production kicked off in Asia, where the industry grew rapidly.[3]

Seaweed cultivation first arrived in the United States in the same era. In 1972, U.S. researchers began growing kelp, which they hoped to convert to methane to use as a fuel source. Several experimental offshore kelp farms were launched in California during this period. Kelp farming proved economically uncompetitive with fossil fuels, so this early effort never grew to scale. In 2019, the U.S. produced 3,394 tonnes of seaweed — just 0.01% of the global supply — most of it wild-harvested. For comparison, China, by far the world leader, produced more than 20 million tonnes, nearly all farmed.[1]

Nonetheless, the industry in California has been quietly expanding. Seaweed has been grown in land-based tanks in California since the early days of abalone farming in the 1970s; farmed seaweed was used as a feedstock for the abalone. The first land-based facility focused on growing seaweed for human consumption, Monterey Bay Seaweeds, was launched in Moss Landing in 2015. The first pilot-scale commercial open-water seaweed farm in California opened in 2020 in Humboldt Bay. In 2021, two more operations received permits, one for a research farm and one for a demonstration project.

How is seaweed grown?

The details of how seaweed grows vary widely, depending on the species and the choices a farmer makes. Seaweed aquaculture production can be broken into two major methods, based on reproduction: sexual and asexual.

Let’s start with asexual production, the simpler of these processes. Some seaweed species have the ability to fragment and regenerate: break one piece of seaweed in two, and, under the right conditions, both will continue to grow. This is the case for many of the species harvested for carrageenan, a compound used as a thickener and binder in food, medicine and cosmetics.

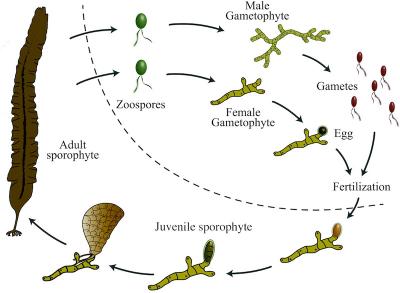

Seaweed species that reproduce sexually have a more complex life cycle, involving two very different generations. The more familiar generation is called a “sporophyte”: picture the large fronds that a farmer wants to harvest. Sporophytes, though, are asexual; rather than reproducing via fertilized eggs, a sporophyte produces “zoospores” that grow into the second generation, known as “gametophytes.” Gametophytes, though microscopic, reproduce sexually: males produce gametes (akin to sperm) and females produce eggs. These join to produce a new sporophyte. The rapid growth of commercial seaweed farming species in Asia depended on grasping this multi-generational lifecycle.

The farming of species that reproduce sexually can be broken into a two-phase process. First, during the hatchery phase, farmers produce “propagules” — the structures that will grow into a new plant — and set them in the appropriate environment.

Next comes the growout phase, which, as the name implies, is when seaweed grows to harvestable size. One key choice is whether to grow seaweed onshore, in tanks or ponds where environmental conditions can be somewhat controlled, or in the ocean. The latter is often a more cost-effective option and is necessary to produce many of the ecological benefits that are driving interest in seaweed.

One common method of onshore production is known as “tumble culture”: a steady flow of air emerges from the bottom of a tank, keeping the seaweeds “tumbling,” suspended between the tank bottom and the water surface. Typically, in open water, seeds or fronds are attached to ropes or nets that are set into the water.

Currently, most open-water seaweed farming occurs in sheltered nearshore or intertidal environments. Often, cables or ropes known as “longlines” are attached to concrete moorings and, using buoys, float at the appropriate depth. Sporophytes are typically attached to thin, tightly spooled strings in onshore hatcheries, under ideal light and temperature conditions. After the sporophytes have attached to the string in the hatchery and begin to grow, the string is unspooled and wrapped loosely around the thicker longline at the farm’s growout location. As the baby sporophytes grow, they attach to the larger longline, which is capable of supporting the seaweed until harvest.

Part of the appeal of nearshore environments is their accessibility, which keeps labor costs low. However, given the competition for suitable sites from industries like commercial fishing, shipping and tourism, there is increasing interest in offshore production, including at wind farms. Researchers are still working to find ways to efficiently and effectively cultivate seaweed in such conditions; one particular challenge is keeping farm infrastructure safe during storms.

There is also increasing interest in “integrated multi-tropic aquaculture,” where seaweed and fish farming could be conducted together. The nutrients from fish feces can help fertilize the seaweed, which also cleans the water; the seaweed, in turn, can be harvested and used for various purposes including food and pharmaceutical and chemical production.

How is seaweed aquaculture regulated?

For onshore production, a farmer needs to register with the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and, if a structure like an intake pipe is going to be installed on public lands, obtain a lease from the State Lands Commission. Depending on the size of the facility, permits for seawater intake and discharge may be needed from various state and federal agencies.

For open-water seaweed production, there are three steps a farmer must take:

- Obtain a state water bottom lease;

- Complete an environment review;

- Acquire permits for farming on the lease.

GreenWave, a nonprofit that supports ocean farming, estimates that the entire process will take a California farmer at least three and a half years, and potentially up to a decade.[4]

A water bottom lease is required because even when seaweed grows in the water column, some gear is typically anchored on the bottom. For state waters, which extend three nautical miles beyond the coastline, the Fish and Game Commission grants the leases after consulting with the Department of Fish and Wildlife. (Though as of February 2023, no new water bottom leases had been granted by the state for more than a quarter century.)

Per the California Environmental Quality Act, an application for a state water bottom lease also triggers the Fish and Game Commission to launch an environmental review. Once this review is complete, a farmer must apply for permits from various state and federal agencies. The specific list of permits required will depend on the particulars of the proposed project. Prospective farmers should consult the state’s permit guide, which serves as a good starting point for exploring the application process.

California has stricter environmental regulations than many other states, which can make launching and managing a new operation difficult. GreenWave estimates that the full cost of an environmental review can reach half a million dollars. These high costs, combined with the slow timeline, are a likely deterrent for many small-scale farmers. Some proponents of seaweed farming suggest the existing regulatory system in California should be reformed since it was designed for commercial shellfish farming, not seaweed.[4]

There are several locations where the state has assigned jurisdiction to local entities, including Agua Hedionda Lagoon, the Port of San Diego and Ventura Harbor.[4] Humboldt Bay, the site of the first in-ocean seaweed farm in the state, is also under local control.

What markets exist for seaweed?

The red algal genera Kappaphycus and Eucheuma, mostly grown to produce carrageenan, make up a third of global production.

The brown genera Laminaria and Saccharina, which are consumed by people directly, make up another third.[5] In Southern California, giant kelp has attracted attention as a potential alternative energy source.

Green algae currently make up a small portion of global production, though some species such as sea lettuce are grown for consumption.

How is seaweed processed?

After seaweed is harvested (sometimes manually, sometimes via boat-mounted mechanical equipment), it must be processed. The specific techniques will depend on how the seaweed is used. Though some seaweed is eaten raw, even in these cases, the seaweed must be properly stored to retain its moisture content and prevent the growth of pathogens. For other culinary products, the seaweed must be dried, blanched or cut into noodles.

For non-culinary products, processing tends to be more extensive. When seaweed is harvested for use in animal feed, it’s dried and hammer-milled.

Seaweed harvested for bioactive compounds follows a similar sequence, though the milled seaweed is pretreated with chemicals that disrupt the cells, making the desired compound more easily extractable. The final extraction method will depend on the compound being harvested but can include treatment with solvents or steam distillation.

To produce biofuels, various biological and thermochemical conversion techniques can be used – from fermentation to pyrolysis.

What challenges might the seaweed industry face as it grows in California?

Competition for space is one of the seaweed industry’s biggest challenges in California, as along all the world’s coastlines. Even beyond the intertidal and nearshore zones, California’s waters tend to be busy — used by commercial shipping companies and military vessels, protected for wildlife, occupied by oil platforms. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is currently studying the Southern California Bight in an effort to identify regions suitable for commercial aquaculture.

It’s also worth noting that seaweed is not a remedy to all problems. Despite the ecosystem services provided by seaweed, altering an ecosystem can have negative effects, whether due to deposition of new biological materials in the benthos or the presence of production gear.[6] There is a tradeoff between a strong regulatory environment system, meant to ensure such impacts are minimized, and the speed of the industry’s growth.

Finally, the same ecological issues driving interest in seaweed will also impact the industry. For example, sugar kelp, currently the most commonly farmed species in the U.S., is sensitive to rising temperatures and marine heat waves.

What solutions and new technologies are being pursued?

The National Sea Grant network has established an online Seaweed Hub as a science-based, non-advocate resource for the domestic seaweed aquaculture industry. Locally, California Sea Grant is one of several sponsors of the California Seaweed Festival, which helps promote this growing industry and connects growers, scientists, consumers and policymakers.

Researchers are investigating innovative approaches to seaweed aquaculture. One Sea Grant-sponsored study is assessing how golden kombu, a native California seaweed species, will fare as the climate changes, and whether it might serve as an effective substitute for sugar kelp, a popular climate-impacted species. Researchers are also seeking new applications for seaweeds to provide even further environmental benefits. Luke Gardner, a California Sea Grant extension specialist, is investigating whether local species, if fed to cattle, can reduce the amount of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, that is released from farms.

Various local ports are creating innovation hubs, efforts to reduce barriers to entry into seaweed farming. The Aquaculture & Blue Technology Program at the Port of San Diego, for example, supports a startup called Sunken Seaweed, which is growing a variety of species on a quarter-acre plot in San Diego Bay. Sunken Seaweed is also collaborating with researchers at San Diego State University’s Kelp Ecology Lab to assess the effects of farming on the bay’s ecosystems. Larger aquaculture companies in the state are also drawn to seaweed cultivation. For example, Hog Island Oyster Company has recently initiated a collaboration with Sunken Seaweed at their Humboldt Bay site, allowing Sunken Seaweed to farm local seaweeds in tanks onshore. This project was also supported by the Port of San Diego’s Blue Economy Incubator.

Do you have a question about seaweed aquaculture in California? Email us at casgcomms@ucsd.edu and we may answer it here.

References

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Global seaweeds and microalgae production, 1950–2019” (2021.).

[2] Dillehay et al., “Monte Verde: seaweed, food, medicine, and the peopling of South America,” Science (2008).

[3] Simbajon and Ricohermoso, “Developments In Seaweed Farming In Southeast Asia,” Proceedings of ADSEA '99, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (1999).

[4] GreenWave, “Guide to Navigating Lease & Permit Approvals for Ocean Farming in California.”

[5] Zhang et al., "Global seaweed farming and processing," Food Production, Processing

and Nutrition (2022).

[6] Theuerkauf et al., “Habitat value of bivalve shellfish and seaweed aquaculture for fish and invertebrates: Pathways, synthesis and next steps,” Reviews in Aquaculture (2022).

Header image courtesy of GreenWave/The Nature Conservancy

Reviewed by California Sea Grant Extension Specialists:

- California Seafood Profiles

- Aquaculture in California

- Discover California Commercial Fisheries

- Seaweed Aquaculture

- Kelp

- Coastal Hazards & Resilience

- Marine Protected Areas

- Red Tides in California

- King Tides

- Rip current safety

- FAQ: California’s Marine Heatwaves

- FAQ: Droughts & California’s Coastal Regions

- Estuaries: Connecting Land to Ocean

- Street Trash Monitoring Protocols and Educational Curriculum

- Safely Viewing Marine Mammals

- Grunion: bridging land and sea

- Delta Smelt

- Recursos en Español