Beginning in 2014, California’s coastline suffered a severe marine heat wave. An expanse of unusually warm water known as “the Blob” hovered in the Pacific, wiping out much of the state’s kelp forests, especially in Northern California.

“The loss occurred quickly, it was dramatic, and it was really shocking to many ocean users,” says Dr. Jennifer Caselle, a research biologist at the Marine Science Institute, University of California, Santa Barbara. The strong public reaction was due partly to kelp’s beauty and iconic status — but also, just as important, its role as a keystone component of the ecosystems that underlie many coastal industries, from the recreational abalone harvest to the commercial fishery.

“So everybody wanted to do something about the loss,” Caselle says. “But it was important to put some data behind that energy so that any actions taken by agencies, the public or conservationists would be informed by science.” That led Caselle to assemble a team that could create a statewide “decision framework” — guidance allowing community groups and governmental agencies to determine where, when and how to restore kelp in California. With funding from the California Ocean Protection Council, California Sea Grant supported the research, some of which was recently published in the journals Ecological Applications and Biological Conservation — and which is already impacting the state’s restoration efforts.

A data-driven solution

Happily, California possesses an unusually robust collection of long-term datasets. For example, Caselle and Dr. Mark Carr, a marine ecologist at UC Santa Cruz and another primary investigator on the project, hold leadership roles with the Partnership for Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans (PISCO), which for decades has conducted scuba surveys of kelp and sea urchin dynamics. The state has also invested in detailed mapping of its seafloor.

“California has invested heavily in its ocean environment,” Caselle says. “Continued investment in long-term monitoring is super important to understand the rapidly changing ocean. We know that it is not easy for state agencies to continue, but it is critical. This research could not have been done without long-term data”.

The teams’ first step was to document and understand the past long-term dynamics of kelps. Using the in-water kelp surveys, the researchers analyzed three key categories of data to understand what drives changes in kelp forests. First, they looked at ocean conditions like temperature, nutrients and wave action. Second, they examined California's detailed maps of the seafloor to understand where different habitats — sand versus rock, for example — existed along the coast. Third, they incorporated ecological data from the scuba surveys, including the density of sea urchins and their predators. The January 2025 issue of Ecological Applications includes a paper by the team — which also included UC Santa Barbara postdoctoral researcher Dr. Anita Giraldo-Ospina and Dr. Tom Bell of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute — describing how these factors influence kelp’s spatiotemporal changes.

Thanks to the very large number of sites included, the researchers were able to build from these parameters a model that allows interpolation to sites that had never been surveyed — the entire California coastline, ultimately.

“And the model is at a really high spatial resolution,” says Giraldo-Ospina, who led the work. It divides the coastline into “pixels” — each 300 meters tall and 300 meters across, roughly the size of three city blocks — and estimates kelp populations in each before the marine heat wave.

That yielded key information for restoration projects, since one key principle is to avoid sites where there’s never been kelp. But the model allows for far more granular consideration, too: The long dataset revealed how kelp populations fluctuated in the decade before the heatwave, helping identify sites where kelp populations were historically unstable. “You want to think hard about putting your conservation dollars there, because after you restore the kelp might be gone in a year,” Caselle says.

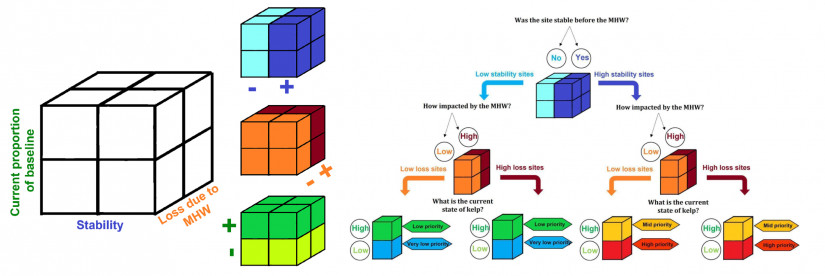

Kelp stability, though, was only one criterion. By adding in data from satellite imagery, developed by Bell, the team was able to consider two other questions, as well: How much kelp was lost between 2014 and 2019 due to the marine heat wave? And, perhaps most importantly, what proportion of the baseline population persists today? When these three criteria are mapped together, they create a three-dimensional classification system that helps identify the most promising sites for restoration. Sites with historically stable kelp populations that experienced significant losses and haven't yet recovered, for instance, might be prime candidates for restoration efforts. The resulting decision tree — really a decision cube, given the three dimensions — was published in the February 2025 issue of Biological Conservation.

From analysis to action

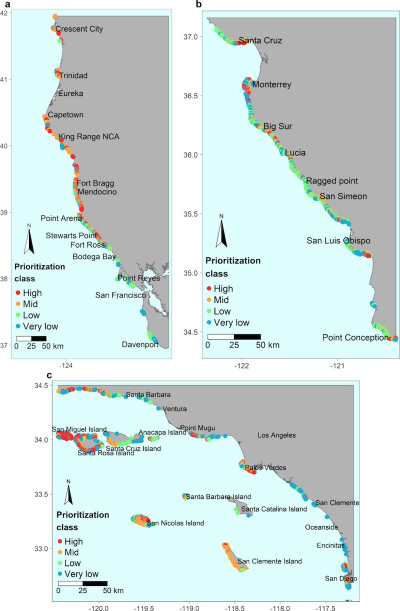

Caselle’s team also produced maps that display the California coastline as a line of colored dots. With red signaling the highest priority and blue the lowest, the maps suggest at a glance where resources might be focused.

“These maps are just one piece of information,” Caselle emphasizes. “There are a hundred other considerations to account for when choosing a location for restoration”: cultural factors, economic concerns, logistical constraints. Caselle notes that many projects focus on getting local communities involved, a factor that may influence site selections.

The project — officially titled “Where, when, and how?” — always meant to go further than just site selection. The completed work already offers some answers to the remaining questions: The model, for example, can help suggest when to restore, since some of its variables, like water temperature and nitrate levels, have clear temporal patterns. Because the model also includes urchin densities, it can also suggest what actions might be most appropriate: Does it make sense to cull urchins, a kelp predator, due to their abundance? Or do the conditions suggest simply outplanting kelp is sufficient? The prioritization level implies further details about what actions to take next, too: Historically stable sites that resisted the effects of the Blob, for example, should be monitored; at such sites, further studies could help reveal what mechanisms allowed them to survive, informing future projects.

Looking to the future

Caselle and Giraldo-Ospina have seen their maps put to immediate use. The project was funded by the Kelp Recovery Research Program, a joint initiative of California Sea Grant and the California Ocean Protection Council, and given the urgency of the kelp crisis, the two organizations decided to fund a second round of projects last year. Applicants were specifically asked to consult these prioritization maps. The Nature Conservancy in California is already using them to guide a major restoration effort along the North Coast and the Gulf of Farallones National Marine Sanctuary has incorporated them into restoration work, too. In Santa Barbara, local fishermen are using the maps to identify sites for a pilot project to remove purple urchins.

“Good science helps ensure there’s more good science,” says California Sea Grant director Shauna Oh. “It’s always heartening to see that a project we funded helps refine the quality of our future work.”

Caselle, Giraldo-Ospina and Bell have received some of the new Accelerating Kelp Research and Restoration Program funding — which the team is using on what she calls a “proactive response” to kelp loss, rather than just quick reactivity. The team aims to create something like a farmer's almanac for kelp restoration practitioners but with a much longer view by forecasting kelp’s future in California.

“We want to be able to tell people when and where a restoration effort might be most likely to succeed, given both short-term environmental conditions and the longer-term changes to the climate. For example, if there's a high likelihood that next year is going to be another heat wave, now might not be the best time to start restoration,” Caselle explains. The goal is to help communities make informed decisions about where and when to invest in restoration efforts. “These restoration decisions are always complicated, always multi-faceted,” Caselle says. “But the science can at least allow us to go in with open eyes.”

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.