Not long after she arrived at San José State University as a biology professor in 2020, Maya deVries noticed that California Sea Grant was seeking research proposals. The call was fitting, as it was for new faculty members in California. The one problem was that it prioritized research on aquaculture.

“I’d never worked on aquaculture before,” deVries says. Still, she knew enough to recognize an opportunity.

deVries’ previous work had focused on “marine critters with shells and exoskeletons,” as she puts it. She’d looked into how these organisms will be impacted by ocean acidification, an ongoing process in which the world’s seawater is growing more acidic as it absorbs more carbon dioxide. Such changes in acidity can make it harder for those critters to build their shells and exoskeletons, which made deVries suspect that some shellfish aquaculture farms would face a challenge in the coming years.

Then, she caught wind that some of her colleagues at San José State were already considering strategies to help California’s abalone farms adapt to more acidic conditions. After speaking with them, she realized her expertise could be a value-add. She had her project — one that would change not just her trajectory as a researcher, but the lives of her students, too.

The acid and the abalone

The story of abalone illustrates just what a conundrum ocean acidification is — for shellfish and humans both. Several species of this sea snail were once treasured foods along the West Coast — the “quintessential California seafood,” deVries says. But overharvesting caused the commercial fishery to shut down in 2010; nine years later, recreational harvest was forbidden, too. Now, aquaculture is the last remaining source for California abalone, and there are only three active commercial abalone farms in the state. Even when abalone are grown in tanks, seawater is used to maintain them, so the threat out in the ocean is a problem for farms, as well.

Two ecologists at San José State’s Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, Scott Hamilton and Michael Graham, had theorized that, since seaweeds absorb carbon dioxide, growing abalone alongside red dulse seaweed might help increase the pH in a farm’s tanks, thus lowering the acidity and buffering some of the impacts of ocean acidification. There were other reasons to grow the two species together, too: the abalone’s waste provides nutrients that help the dulse grow; the abalone eats the red dulse in turn — which saves feeding costs. Any excess dulse can also be harvested and sold. The experiment they set up was an example of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA), in which different species of a food chain are grown together.

Hamilton and Graham’s research — which was funded by California Sea Grant and published in Aquaculture in 2022 — found that adding the seaweed to the tanks did indeed help increase the pH of the water and, further, made the abalone grow faster. They had hoped to investigate what that faster growth meant for the abalone shells, but had not yet tackled that question.

From material science to mentorship

In partnership with Graham and Hamilton — as well as their industry collaborator, Monterey Abalone Company — deVries was awarded funding from California Sea Grant to conduct further IMTA experiments. She found that growing abalone with seaweed in less acidic conditions produced the strongest, thickest shells. This suggests the seaweed creates a more favorable environment for shell construction — an insight that can benefit growers now. When the team conducted a follow-up experiment examining growth and shell construction under extremely acidic conditions, the results were even more apparent: Animals grown in extremely low pH were visibly weaker and smaller, while those grown in moderate pH and ambient seawater were much bigger and stronger.

As a part of the grant, deVries hired a master’s student, Noah Kolander, and several undergraduate students to assist with the research. She soon realized that incorporating students into the project had its own value, helping create a pipeline of future aquaculturists. So she successfully obtained further funding from California Sea Grant to formalize and expand this mentorship aspect of the project.

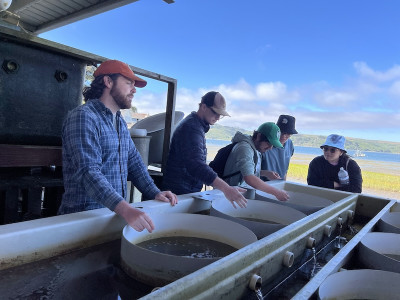

Each spring, a new cohort of undergraduates joins the resulting program, called Aquanauts. Over an intensive, six-to-seven-week period in the summer, the students assist with the ongoing abalone IMTA research at Moss Landing. Some students graduate at summer’s end; others stay on throughout the next school year, incorporating the research into their senior theses — which, as deVries notes, means the students can be included as co-authors on published research. California Sea Grant’s funding also helped cover the stipend for a graduate student mentor for the undergraduates, Kierstin Thigpen, who helps oversee the students' work.

Into the field

One of the benefits of the Aquanauts program is that students who stay on don’t need to look for outside jobs to pay for tuition; they’re getting paid to do work that complements their academic journey. But deVries also wants to broaden the students’ understanding of aquaculture. Working at Moss Landing, they get exposed to research into other species, too, like oysters and urchins.

A key part of the Aquanauts program, deVries says, is a weeklong field trip in which students experience the entire supply chain, from farm to plate: the group visits the Fishery, a commercial aquaculture company that produces, among other species, sturgeon; the Bodega Marine Lab at the University of California, Davis, which focuses on white abalone production for conservation; Hog Island Oyster Company, one of the best-known oyster producers in the country; and Fish., a restaurant in Sausalito that highlights sustainable seafood. The students also tour the restaurant’s owner’s seafood distribution company in San Francisco, which focuses on sustainability.

One of the program’s major goals is to help students make their next steps within the field. Of the current cohort, one undergraduate will be staying on at Moss Landing for a master’s program in urchin aquaculture; another has taken a job with the state Department of Fish and Wildlife. Yet another student is applying to law school to pursue environmental policy — which deVries sees not as a departure, but a success. “We are excited if our students go into academia or industry or policy — any of those are great,” says deVries. “No matter where they wind up, we think it’s useful to have more people entering the aquaculture field with an emphasis on sustainability.”

By this metric, you can count deVries as a success, too. The work with abalone over the last five years has turned her into a “total convert” to the world of aquaculture, she says. Some 17% of the protein consumed by humans comes from the ocean, she notes, but only a small portion of that is sustainably sourced. “The more ways we can discover to produce sustainable seafood, the better that is, not just for California, but for the world.”