Tucked away from the exhibit halls of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles (NHMLA), where visitors crowd around T. rex skeletons and a 10.8 pound gold nugget found in the Mojave desert, lies an unheralded treasure — but one that has recently proved essential. The museum’s fish collection comprises quiet hallways of movable shelves sit jar upon jar containing about three million specimens, from a tusked goby smaller than a quarter to young giant sea basses that can reach up to seven feet fully grown.

Almost every fish family is represented, often with several specimens, collected at various times during the decades since the museum was founded in 1913. It is one of the largest fish collections in the country. And researchers are hoping that somewhere in its crowded shelves lies the answer to a question that is being asked with increasing urgency: For how long have fishes in California – and, by extension, other animals and people in the state and elsewhere – already been exposed to microplastics?

The Rise of Plastic Pollution

“We are effectively a working time machine,” says NHMLA’s Associate Curator of Ichthyology William Ludt. Over the past 18 months, Ludt — together with NHMLA Curator of Mineral Sciences Aaron Celestian and marine biologists Jessica D. Flores and Jazmine Gallardo — has pulled from the shelves jars of fish that were collected as far back as the 1940s to check for traces of plastic. “We can go back in time and physically hold and study species that were present,” he says.

The first fully synthetic plastic, called Bakelite, was invented in 1907, but industrialized production of plastics really revved up during World War II. Unlike some of the natural materials it replaced — think wood — plastic never rots. However, scientists soon recognized that plastics do degrade over time, particularly plastic debris that has been swept into the ocean. There, exposed to the sun’s harsh UV radiation and tossed around by the waves, it turns brittle and breaks into smaller and smaller pieces.

Only during the last 15 years have researchers realized how prevalent such fragments have become. Microplastics — defined as particles that can be up to the size of an uncooked grain of rice but are often much smaller — have been detected on the bottom of even the most remote oceans, in polar ice far from human settlements and floating in the atmosphere. According to a 2021 Nature study, crumbles of this man-made material now make up 60 to 80% of marine debris, rendering it more prevalent than shells, seaweeds, wood and other natural detritus. Animals eat microplastics and their even smaller brethren, nanoplastics, with their food, inhale them with the air they breathe, swallow them in their drinking water. A study earlier this year showed that the average human accumulates enough microscopic fragments in the brain alone over the course of a lifetime that, reassembled, they could form an entire plastic spoon.

Scientific Detective Work

When did this build-up of plastic in the environment start? That’s the question Ludt’s study, the first of its kind for fish from the Pacific Ocean, aims to answer.

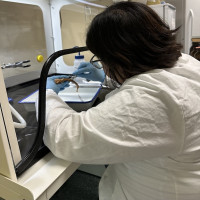

The team focuses on six species, ranging from plankton feeders like northern anchovies to algae-feeding opaleye and predators living deep in the ocean such as the Pacific viperfish. Ludt and his collaborators carefully extract the stomach of every specimen, then dissolve it in a strong basic solution. Bubbling and fizzling, the chemical breaks down the biological material but leaves any plastic untouched. Whatever plastic fragments Ludt’s team find, they run through a machine called a Raman spectrometer, which hits the plastic with a laser. This causes “the plastic to release some of its chemical compounds that lets us identify what type it is,” says Ludt.

So far, the team has detected fragments of plastics in specimens dating back to 1956. From 1960 on, plastic’s presence becomes “fairly consistent,” says Ludt. “Essentially, immediately after plastics are mass-produced we see it throughout the environment.” It doesn’t seem to matter if a fish feeds on algae, plankton or other fish — once plastic arrives in the environment it shows up in fishes’ stomachs, regardless of their lifestyle. “Every species we've looked at has microplastics in it,” says Ludt. “Every single species.”

A Multigenerational Problem

The three researchers have yet to analyze some of their earliest samples, from the 1940s, which means that the timeline could shift even earlier. But already their findings suggest that plastic pollution has been going on for much longer than humans had realized. “It drives home the point that it's not just us that have microplastics in us, but likely our parents, likely our grandparents,” says Ludt. “Plastic pollution has been around for quite some time.”

Medical scientists are still unraveling how ingesting plastic fragments can impact living beings. But in studies so far, microplastics have been associated with issues such as inflammation, infertility, metabolic disturbances and other health concerns.

For Ludt, finding microplastics in decades-old museum specimens wasn’t necessarily a surprise. Most of the plastic humanity produces ends up being discarded, he knows. Between 1950 and 2015 alone, approximately 6,300 million metric tons of plastic waste were generated worldwide. That’s enough to fill New York City’s Central Park with plastic waste as high as the Empire State Building roughly twice a year — for the last 65 years.

What did take Ludt aback, however, was just how much of the material he encountered in the fishes’ stomachs. “I didn't expect that some individuals were going to be so full of plastic,” he says. “That is the biggest shock.”