One of the tools that helps us understand California’s coastal ecosystem is so unassuming that it’s easy to overlook. But in the belly of the research vessels owned and operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in California, if you look closely, you’ll find a plexiglass box affixed to a series of tubes.

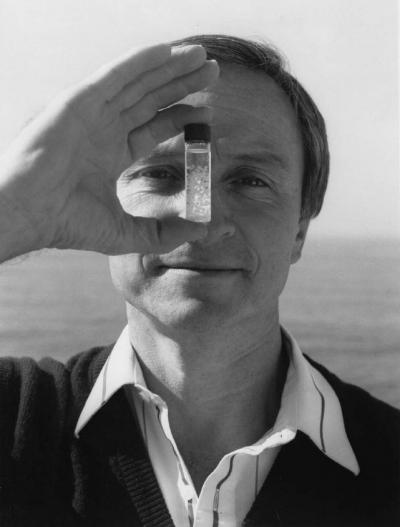

The Continuous Underway Fish Egg Sampler, as this contraption is known, has provided essential insights to global marine science — establishing a new and more effective method for tracking the spawning events of important fish species. And California Sea Grant helped show the world how useful it could be, says its inventor, biologist David Checkley.

An imperfect storm

This powerful little device was first prompted by an observation Checkley made in the late 1980s: Atlantic menhaden, an ecologically important fish that ranges from Nova Scotia to Florida, tended to spawn following emerging “bomb” cyclones.

These storms, caused by rapid drops in atmospheric pressure, can be tremendously dangerous to humans. But they offer an advantage to fertilized fish eggs in the Atlantic: the northeasterly winds carry eggs in recently upwelled water to coastal estuaries with plentiful food. By responding to these bomb cyclones, spawning fish can (to twist a cliche) lay all their eggs in one basket, at the right time and in the right place, to ensure higher survival rates.

But this behavior causes problems for biologists. The standard practice in oceanographic sampling is to break a region into a grid. A vessel travels to each point, where scientists drop nets to see what they find. Since menhaden lay their eggs in huge volumes but only in small areas, they can be easily missed. Checkley figured rather than a point-by-point approach, continuously sampling along a line raised the chances of stumbling across the spawn.

A new tool

The Continuous Underway Fish Egg Sampler or CUFES — pronounced “coofs” — was Checkley’s answer, though its precise form shifted through the years.

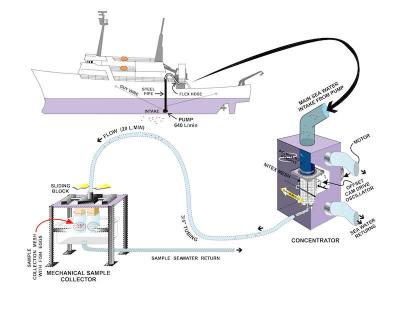

The original system consisted of a submersible pump mounted on the exterior of a boat at a depth of three meters. Every minute, the pump delivered 650 liters of seawater into a box known as a concentrator. An oscillating mesh cone, mounted inside the concentrator, captured anything larger than 500 microns to be sent onward via smaller pipes to a collection device that is accessible to researchers. (The rest of the water, and whatever smaller particles slip through the mesh, was poured back overboard.)

Checkley was a researcher at North Carolina State University when he first developed CUFES. In 1993, he moved west to take a job as an associate professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO). After a discussion with John Hunter, the director of the Fisheries Resources Division at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Checkley decided to rig his system onto one of the agency’s sampling vessels — no small task, given the laborious installation process.

“It blew John’s socks off,” Checkley remembers. That launched a long-term collaboration, and in 1996, CUFES was incorporated into the California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations (CalCOFI). This quarterly program of cruises is conducted as a cooperative venture by NOAA’s Fisheries Service, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and SIO.

A California connection

CalCOFI gathers data on the physics, chemistry and biology of the ocean to inform the sustainable management of marine ecosystems. CUFES allowed CalCOFI to gather more data about the abundance and distribution of the eggs of sardines and anchovies, “forage” fish that form a key part of the ecosystem. The device proved so useful that it has been routinely installed on new NOAA fisheries research vessels. On these vessels, the pump is submerged in a water-tight container inside the hull of the boat, known as the “sea chest,” which is open to the sea at a three-meter depth.

California Sea Grant got involved almost as soon as CUFES appeared on CalCOFI cruises: Checkley began to receive funding to assess ways to improve the system in 1997. One question was whether CUFES could be automated. Checkley field tested a machine-vision system that analyzed images of the eggs to determine their species during the spring CalCOFI cruises in 2003 and 2004. The device collected millions of digital images, but Checkley found that the eggs appeared similar to bubbles, making the images difficult to analyze.

Sea Grant funding, though, did help Checkley develop a method by which to create near real-time maps of fish egg abundance. The eggs collected within the concentrator are gathered at regular intervals; the shorter the interval, the more precise the resulting geographical data, since a shorter time period means a shorter distance at sea.

This means that researchers must be on board to analyze the eggs using a microscope to determine their species. The work can be difficult in rough weather. The fish eggs and krill in the sample are jostled as the boat is rocking in the waves. “You don’t want to be a person who gets seasick looking through a microscope, trying to count things that are moving around,” says Amy Hays, with a smile. Hays, a NOAA researcher, has been using CUFES since Checkley brought the tool to California in the 1990s.

On NOAA cruises, the eggs are now collected every 30 minutes, which at a ship speed of ten knots means each sample contains eggs from a six-kilometer line. For other data on CalCOFI cruises, it can take scientists months, or sometimes as much as a year, to produce any meaningful results. With CUFES, though, maps of egg distribution can be updated and released on a daily basis.

Now, 40 years on, CUFES is still spreading. “A lot of different countries use the CUFES system that we’ve helped implement,” Hays says: Chile, France, Portugal, India, Australia and South Africa. “It’s a very useful tool in many different fisheries.”

Checkley is particularly proud that the data collected on CalCOFI cruises inform assessments of fish stocks — which are used to establish catch limits, thereby having a direct impact on local fishing communities. California Sea Grant, he notes, often focuses on such research, meant to benefit local fisheries and the people who depend on them.

“That's one of the most gratifying things about science, when you can make that personal connection,” he says. “I almost get choked up when I talk about this.”

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.