Sea Grant Extension Specialist Luke Gardner explains how aquaculture can help restore giant kelp, reduce methane emissions and help feed our growing population.

Could you talk about your background and how you started working with Sea Grant?

My background has largely been molecular biology and applications of that to aquaculture, but also just general aquaculture research. I did my undergraduate at James Cook University, and my PhD at Queensland University of Technology in Australia. Then I did a postdoc at Stanford University’s marine campus in Monterey, where I studied bluefin tuna reproduction.

I knew that aquaculture was having a resurgence in the US, and my host organization, Moss Landing Marine Labs, was looking to replace Rick Starr, who was my predecessor there doing fisheries-related work with Sea Grant. He had just retired, and they wanted to get another Sea Grant extension specialist. I'd been wanting to get back into more applied aquaculture, and that's basically what Sea Grant does with a range of different coastal topics, including aquaculture. Sometimes it's kind of hard to wake up in the morning and go to work when you don't really know what you're doing it for. Sea Grant makes that purpose really easy to understand.

You just mentioned a resurgence of aquaculture. How do you see the importance of aquaculture in the US?

For a long time, aquaculture, particularly in the US, has suffered from some bad actors and bad social perception. There were some early cowboy operators that polluted the environment, and that's unfortunately stuck with the industry for a long time. But the reality is: the industry has come a long way, and the US now has some of the highest quality aquaculture products and strictest environmental standards in the world. So people's perceptions of aquaculture are starting to change. In addition to that, there's been a movement in the concept of conservation or restoration aquaculture. This is typically some type of aquaculture that can not only produce food, but can potentially also provide a net benefit to the environment, whether it be through carbon uptake, taking particulate matter out of the water, or restoring endangered species.

In terms of conservation and restoration aquaculture, you’ve been working with purple sea urchins. Would you like to talk about that?

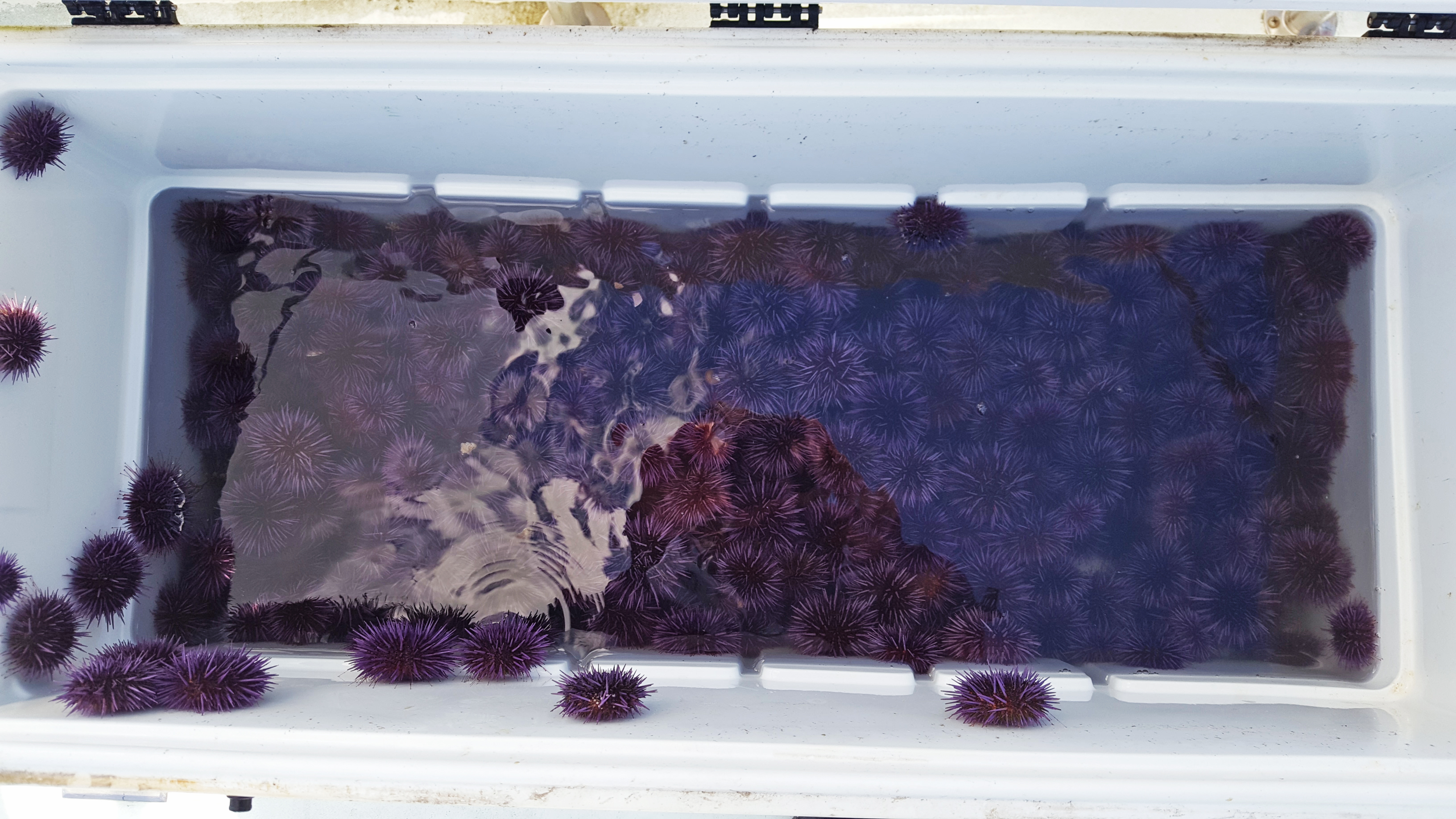

It's one of these great opportunities where the fishing community can work with the aquaculture community, and they can all work together with the environmental NGO community to actually benefit the environment. We've lost a huge amount of our kelp, particularly in Northern California, and it's increasingly happening farther south. There’s an overabundance of purple urchins that are kind of like locusts, except they don't die. They mow through all the kelp and other seaweeds and then go dormant and sit there. Nothing can grow because the moment it pops up, the urchins march over and eat it. This creates barrens, where once there was a gigantic kelp forest, and now it's just rocks with urchins everywhere.

Urchins are ordinarily worth a lot of money for their uni, which is the gonads. The problem is, after they've eaten everything, these urchins go dormant and become emaciated. So we've been exploring the idea of catching them and fattening them up. We did a class project at Moss Landing Marine Labs as part of a course I was teaching. Students collected a bunch of the urchins, sub-sampled them, put them into a series of replicated tanks and fed them different things. Then every couple of weeks, the students would sub-sample a few of the urchins from each tank, process and see what their gonads were like until we decided that they reached a saleable size—about 10-15% of their whole body weight. At the end of that, we took the students to a local Michelin star restaurant—Aubergine in Carmel—and had the chef do a taste test and a class on texture, color and taste.

The next phase of research is adding in an extra layer of sustainability. We're working with Taylor Farms, a big agricultural producer in the area, to see if we can use their vegetable waste to feed urchins. Elsewhere in the world, people have shown that you can feed some of this agricultural waste to the urchins, and as long as you feed the right combinations, they'll still have the right color, texture and taste.

Are there any other ongoing conservation or restoration aquaculture projects you're excited about?

Another project we're about halfway through is looking at the potential of various local seaweeds to reduce methane in cows. This work originated in Australia at my old university, James Cook University. And on the weekends, I'm a cattle rancher. So, I'm also aware of the cattle components.

Methane is a climate pollutant. It's short-lived compared to CO2, but I think it's about 25 times more potent than CO2. The single biggest contributor to our methane emissions in California is ruminant livestock, particularly cattle. And California is the largest dairy-producing state in the US. It has over 1.4 million dairy cows.

The majority of the methane released from cows is through burping. What they found in Australia a few years back is that if you feed certain kinds of seaweeds to the cow, you can reduce the methane by upwards of 99%—at least in a kind of a laboratory in-vitro scale—which is pretty spectacular. And you only need to change 1% of their diet to the seaweed. This is really beneficial to the environment and also to the cattle producer because if they're not releasing methane, that means that they're actually retaining that energy and putting it into growth.

We had an idea to try a similar study here, but use a bunch of native seaweeds from California. We're working with USDA on that. Once we send them a bunch of different seaweeds, they get the fluid that's in the cow’s stomach and mimic digestion and measure all the gases. After that, we get the various different seaweeds that showed potential to reduce methane and see what their aquaculture potential is. While one species might be really great at reducing methane, it might not be well-suited for aquaculture. Then, we select one and grow several hundred pounds of it and do a whole-animal trial with another USDA collaborator in Wisconsin. They'll feed the seaweed to 12 cows over the course of maybe three months and measure methane production.

People are really excited about seaweed aquaculture. I get calls all the time about people wanting to start a farm. But the missing component is, “who do I sell this to? And what do they do with it?” So this could be one of these ways where aquaculture helps itself but also helps the environment and the community at large.

How have things changed for your work in the last few months during COVID?

As part of COVID, a lot of my job has shifted to trying to work out what we can do for the aquaculture industry—to try and help them get through this and then also help harden them for the next time something like this might happen.

The aquaculture industry, particularly in the US, is suffering from COVID. A lot of what we grow is high-value specialty products destined for white-tablecloth restaurants—oysters and abalone and things like that. Because all the restaurants are shut down, their sales have pretty much dropped to zero overnight. It turns out that caviar and oysters and abalone just aren't that necessary in the apocalypse.

Trying to get these products into supermarkets is difficult based on the price and other factors. However, trying to produce more traditional seafood commodity products that you would find in grocery stores is difficult when trying to compete with China and Southeast Asia. Those countries can produce what we produce really, really, really cheaply. That's kind of the nature of any fledgling industry—you do niche stuff until you can get bigger.

Is there anything else you want people to know about aquaculture?

A lot of people say to me, “Oh, gross. I would never eat a farmed fish.” And when you ask them why, they don't know. It's just something they're repeating that they've heard somewhere. Because when you think about it: why don't you want to eat a farmed fish? You eat farmed everything else. Thousands of years ago, we stopped relying on going to the forest to pick berries and hunt animals. We just couldn't depend on that to support the amount of people we have on the planet now. Fishing, while a large and important part of our seafood supply, hasn’t been increasing for decades now and isn’t expected to in the future.

So if we want more seafood—not just seafood, if we want more food, we need to farm it. There's also a lot of evidence to suggest that—particularly when it comes to growing marine animals—it can be done in a more efficient way than their terrestrial counterparts can. So, in some ways, we can produce more animal protein in the oceans in a more environmentally friendly way than we can currently on the land. I like people to keep that in mind when they're thinking about aquaculture.

###

Interview conducted and edited by Erin Malsbury, 2020 California Sea Grant communications intern