Every few years, newscasters in California will pull up an image from King Salmon, a low-lying coastal community in the northern part of the state: Amid a flood, a woman sits on a beach float, holding a cocktail. “She’s having a good time, enjoying the temporary river in the middle of the street,” says Kristina Kunkel, a former California Sea Grant state fellow, who recently co-published a paper investigating how residents of King Salmon are responding to rising seas.

It’s a rare point of levity amid a crush of grim news stories about climate change — which often feature maps depicting the effects of sea-level rise. Regions threatened by future inundation are colored in blue.

Such maps “produce new types of places,” Kunkel and her co-author, California Sea Grant extension specialist

Laurie Richmond, note in the paper, which was published in Climate Risk Management in March of this year. The maps, they contend, turn cities, towns and communities into “sites of contestation and consternation.”

But what do people in the blue zones think of these maps? What do they think of climate change? Such questions — rarely asked — are addressed in the paper.

A hard-hit community

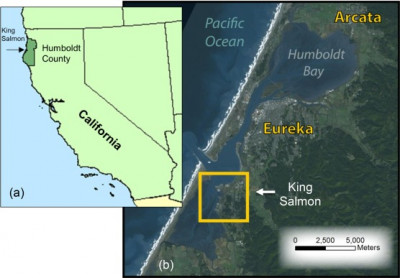

The research was sparked by a news story Kunkel read as an undergraduate at Humboldt State University (now Cal Poly Humboldt): The surrounding region faced the highest levels of relative sea-level rise on the U.S. West Coast, she learned. In King Salmon, in particular, the seas are rising three times faster than the national average.

“That blew my mind,” Kunkel says. She hadn’t even realized that sea-level rise could vary from place to place.

Soon she learned that, due to tectonic activity, the land around Humboldt Bay is sinking, thereby amplifying the impacts of rising oceans. As Kunkel progressed to a master’s degree in environmental studies at Cal Poly Humboldt, she decided to focus on this issue and particularly on the community of King Salmon. Richmond — who, in addition to her role as an extension specialist, is a professor at the university — became her adviser. Richmond is also a co-chair of the Cal Poly Humboldt Sea Level Rise Institute where forwarding knowledge and planning for sea-level rise are a priority.

King Salmon is a low-income, rural, unincorporated community that sits along Wigi, the Wiyot name for Humboldt Bay. The town is built atop “dredge spoil,” or soils that were dug up for other projects and dumped at the site. Its roughly 200 residents mostly live in small homes and trailers.

As a part of her thesis, Kunkel interviewed residents and observed a workshop held by county planners. She found that many people had moved to King Salmon because it was a rare coastal community in California with affordable housing. Those low prices, though, are part of a trade-off: This is a place that floods. One resident told Kunkel that she experienced her first flood the very evening she moved in. Another reported being surprised that, rather than encountering rushing floodwaters, he found it seeping upward through his hardwood floors.

King Salmon is at the front lines of climate change, in other words, and its residents are already developing adaptations. They have waders on the ready and blocks to lift their cars. Kunkel met one man who would print out tidal forecasts and hand them out to neighbors. That way, they all could arrange errands and doctor appointments on dates they knew they’d be able to drive.

“It’s easy to think about climate change as something happening way in the future,” she says. “Like, ‘maybe we don't have to really think about it much yet.’ But King Salmon shows how it’s happening right now. That’s revelatory, for some people.”

Given how few people had heard from King Salmon’s residents, Kunkel’s advisor Laurie Richmond wanted to ensure that the research wasn’t overlooked. So she decided to work with Kunkel to co-author a paper.

Richmond was struck by the sense of humor embodied in that often-shared photo. It seems to denote that King Salmon’s residents see sea-level rise as less of a crisis than the dramatic “blue zone” maps imply. But she and Kunkel found that the residents are also aware that as seas rise, their current adaptations might not suffice.

One woman, Richmond remembers, said that her love for the coast was why she lived there; it also meant that she was willing to leave if that’s what protecting the coast needed. “Communities can surprise you,” Richmond says. “I think as academics or planners or scientists, we sometimes forget about these individual people and how important it is to engage the communities.”

Through this work, Richmond has been reminded, too, about the local knowledge residents possess. They know the “microgeographies,” she says, including places where water tends to pool and stay. She hopes to get local public resource managers to walk the streets with locals so that they can learn about such problem spots. Humboldt County, California Sea Grant and Cal Poly Humboldt have recently received a grant from the California Coastal Conservancy that will allow Richmond and some of her students to help incorporate such local knowledge and needs into a county adaptation plan.

Progress like this encourages Kunkel, who now works as the Deputy State Controller overseeing environmental policy for the State Controller’s Office. Too often planners only engage with community members to tick off a box because policies require them to do so, she has found. When in reality, it offers a chance to uncover knowledge that is “so valuable, and so often overlooked,” Kunkel says.