The giant patch of trash twice the size of Texas, often described as a “toxic soup,” floating in the northern Pacific Ocean has garnered the attention of millions world-wide, making headlines as one the biggest threats to marine life and human health. Ocean clean-up efforts around the globe are helpful but don’t keep up with the source of the problem—us, the consumers on land.

Solutions to marine debris pollution lie, in part, in a better understanding of the types, amounts, and sources of trash items that travel from land into our oceans, and also in educating and engaging community members in trash management efforts. While several widely accepted trash monitoring protocols exist for waterways and wetlands, less attention has been paid to protocols for assessing trash along urban streets. Monitoring urban streets is important as these densely populated areas are sources of much litter that ultimately finds its way through waterways and to the ocean via city storm drain systems.

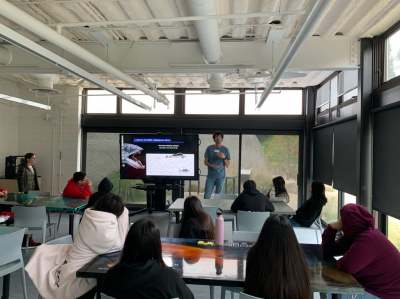

That’s why, in January, I joined California Sea Grant extension specialist Theresa Talley in piloting Trash Troop, a week-long camp that brings an urban trash monitoring protocol and education curriculum to middle schoolers in City Heights, an underserved community in San Diego.

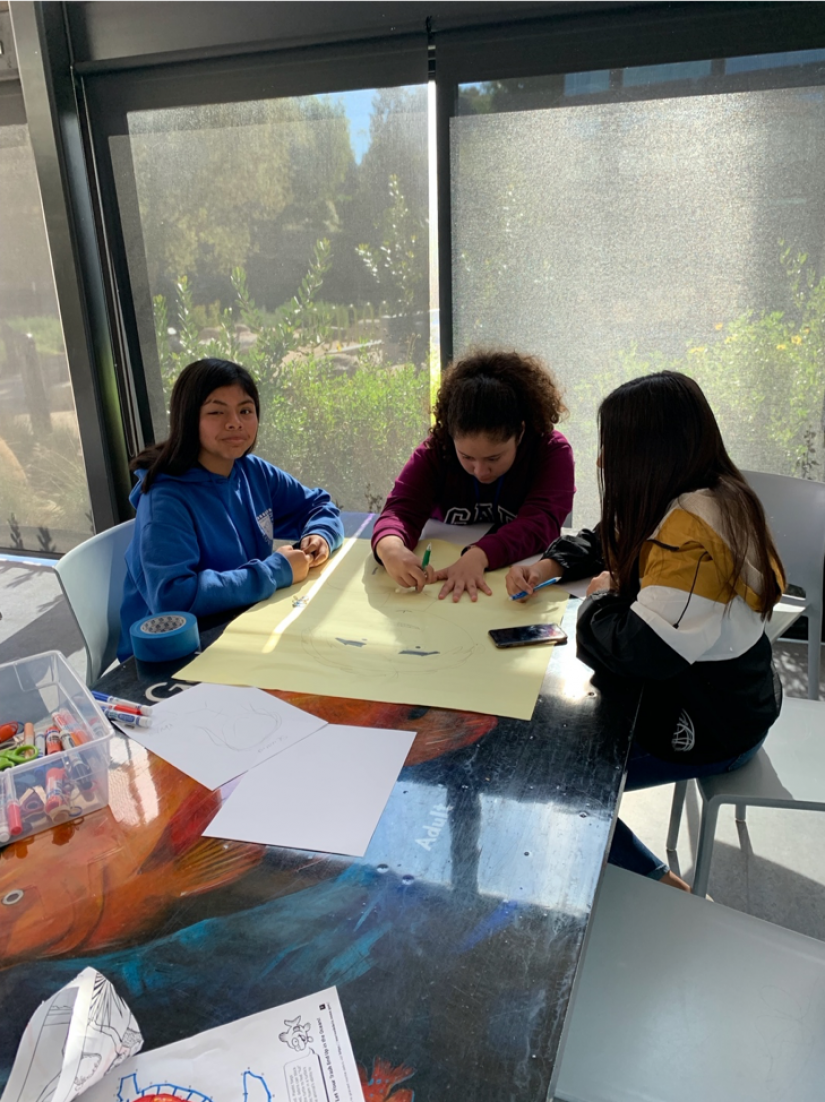

The first camp was in January, and it was both a lot of fun and a learning experience for us all. There were two goals each day—a scientific goal and a personal growth goal. For the scientific goal, we aimed to teach kids about how to conduct science. Throughout the week, we built an understanding of the plastics life cycle: from petroleum-based fabrication, to uses and fates, to effects of leaked plastics on the environment, to exploration of solutions. In piloting the street monitoring protocols the students gained an understanding of the uses, fate, and effects of single use plastics and the importance of science and monitoring in developing solutions. We identified common types of street litter, such as drink cups and snack wrappers, and a look at brands revealed the local convenience stores and fast food restaurants that could potentially help with our quest for solutions.

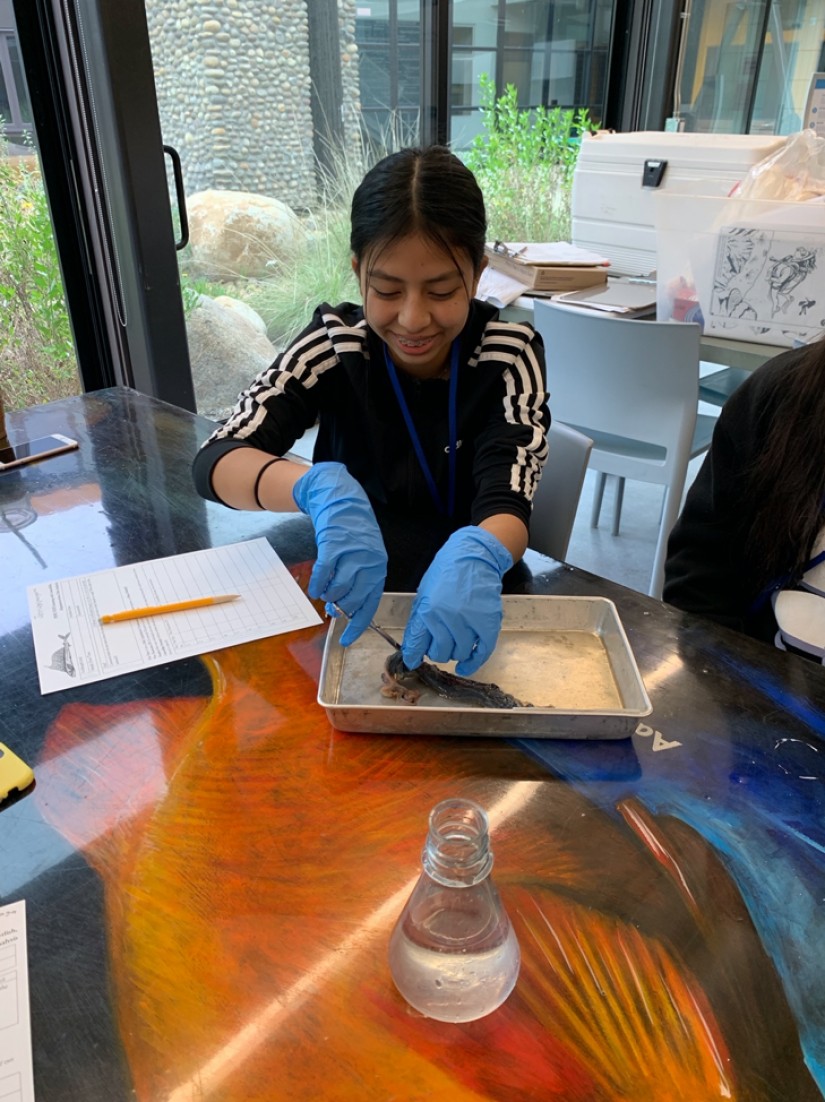

A science highlight of the week was dissecting lancetfish (Alepisaurus ferox), a deep-sea dwelling fish with slow digestion, to glimpse at the stomach contents—including other fish species as well as marine debris—using methods currently used by scientists to study deep sea ecology and human impacts.

“This is the coolest and grossest thing I have ever seen,” exclaimed one student, upon finding various species of deep-sea dwellers within. The dissection also made clear just how far-reaching anthropogenic debris is, as about 30% of lancetfish stomachs that the students dissected contained plastic contents. The lancetfish stomach dissection was generously led by Elizabeth Hetherington, a post-doctoral researcher at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and Elan Portner, a NOAA scientist who both work with Scripps’ Anela Choy on providing plastics awareness curriculum.

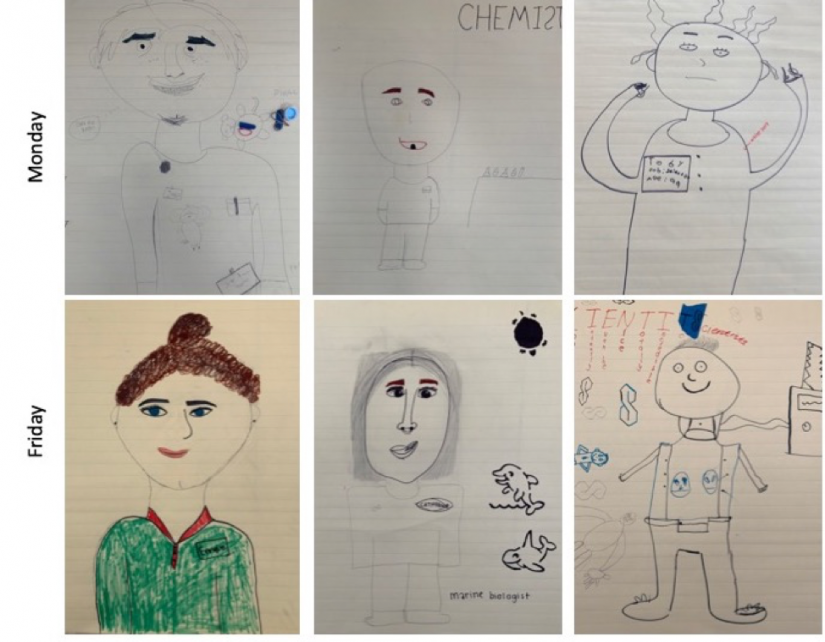

For the personal growth goals, we sought to strengthen collaboration skills, provide career insights, and build a science identity where students began to see themselves as scientists and environmentally responsible members of society. By the end of the week, students’ perceptions of who scientists are had changed from a predominance of white, short-haired older males in lab coats to a whole diversity of people. We saw drawings of brown and white scientists, women and men with long hair, a special needs scientist, people in casual dress, more like what the students were wearing, and scientists outdoors, leaving the confines of their labs to study marine megafauna! This monumental shift in the student’s perception of who scientists are allows them to believe they can become scientists. The camp was capped off by an individual pledge from each student, to take on their own individual – and achievable - stance against marine debris.

Trash Troop is a NOAA Marine Debris Program-funded project to stem the tide of urban trash flows, led by California Sea Grant extension specialist Theresa Talley, with Nina Venuti, and Lupita Barajas, in partnership with Jo Vance, Joel Barkan, and Lupita Sandoval from Ocean Discovery Institute. We are excited to present the camp two more times in late March/early April to the middle-schoolers through Ocean Discovery Institute, stay in touch for more updates on those, via our newsletter, or social media channels.