When the news re-surfaced in 2020 that vast additional amounts of the insecticide DDT had been found off California’s coast, it brought back memories of the time when a large DDT waste repository had been discovered nearer to the shore – which led to litigation, public fears, and frustration. The newly detected cache also raised many questions. How much more of the chemical contaminant has been sitting on the ocean floor for the last several decades? How has this affected the marine environment? The questions and concerns from California communities brought together two Sea Grant programs that decided to approach the issue together.

The University of Southern California Sea Grant (USCSG) and California Sea Grant (CASG) jointly designed a process to approach this complex issue, starting with a workshop in which scientists, community representatives and other stakeholders collectively determined which research questions need to be answered to inform any meaningful mitigation strategy. Recently issued in the form of a report, the workshop’s conclusions are now helping shape how the state will grant funds to investigate the damaging contaminant from the past.

“The report is the unique culmination of a nine-month collaborative and inclusive process to engage the perspectives of leading scientists as well as those of policy, nonprofits, federal and state agencies, formal and non-formal educators and education centers, tribal representatives, anglers, aquatic recreation communities, and interested members of the public,” said Lian Guo, Research Coordinator at CASG who co-led the workshop with Amalia Aruda Almada, Science, Research & Policy Specialist at USCSG.

DDT’s contentious history in California centers around the Montrose Chemical Corporation Plant, which was based in Los Angeles, and between 1947 and 1982 produced more DDT than any other factory in the country. Once hailed as a wondrous substance that could protect crops from pests and soldiers from malaria, DDT (abbreviated from its chemical name dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) was banned in 1972 because it proved to be poisonous for wildlife and potentially carcinogenic for humans. After the domestic ban, Montrose produced DDT for another ten years to sell it abroad to countries struggling to control the spread of insect-borne diseases.

In the 1990s, Montrose and other defendants agreed in a settlement to pay $140.2 million for disposing of DDT waste through sewage pipes into the shallow marine environment adjoining the Palos Verdes Shelf near Los Angeles. The resulting DDT Superfund site is still undergoing periodic monitoring today.

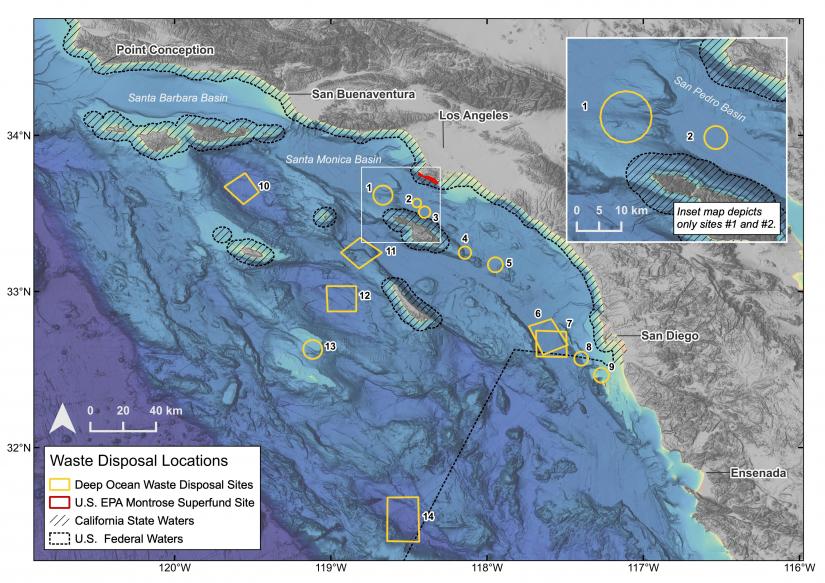

But only recently it came to public attention that as many as half a million barrels of chemical waste stemming from the production of the synthetic pesticide were boated to areas near Catalina Island and thrown into the deep ocean at two designated sites about ten miles from the Palos Verdes Shelf and at depths of up to 880 meters. Additional DDT waste might have been dumped en-route to these two sites.

While the en-route disposal was illegal, the sinking of barrels and bulk disposal at the designated site was in accordance with rules of the time. Back then, it was believed that the ocean would dilute any toxin to harmless concentrations, making it a suitable dumping ground for dangerous substances.

But today’s coastal residents were stunned by the news and left wondering what this meant for their own health as well as the health of the environment.

“There was only a very small group of people who were actively involved in the DDT issue and knew what was going on,” said Guo.

Many others, including tribal communities, felt left out of the loop.

Only two states in the country – California and Massachusetts – have more than one Sea Grant program operating simultaneously within their borders. With such a large problem at hand, the two programs were eager to collaborate to identify what research was most needed moving forward.

“We could have just done a literature review, talked to some technical experts and written a report about what should be done,” said Almada. “But we wanted the community to be co-designers of the process.”

Guo and Almada reached out to scientists as well as community members that they felt should be included in the discussions about how future research on the deep-ocean DDT should be directed.

The area where the new waste deposits were found are part of the Southern California Bight, a 430-mile stretch of coastline that runs from Point Conception in Santa Barbara to Punta Colonet in Baja California and includes the Channel Islands. It contains highly productive ecosystems in diverse seafloor habitats that include rocky banks, seamounts, basins and submarine canyons in which cold, nutrient-rich water from the California Current and warmer water from southern currents mix. Initial studies have shown that in some areas, the DDT concentration in sediments in deep-water parts of the Bight exceeds even those found at the previous Palos Verdes Superfund site. DDT compounds have also been detected in marine mammals living in the area. A recent Marine Mammal Center Study links the pesticide to cancer in California sea lions.

Nevertheless, it’s unclear how much of a threat the chemical contaminant poses. That deep in the ocean – some of the dump sites are almost nine hundred meters under the water surface – oxygen is sparse. This might mean that the DDT has been left relatively undisturbed since few animals are thought to be able to survive in such an environment, although much is still unknown.

Some of the original waste will also have chemically degraded by now, contributing to a suite of breakdown and by-products that scientists have started to refer to as DDT+.

Physically agitating these chemicals on the seafloor – as would happen during remediation – might create more of a danger than they currently present. Clean-up efforts might also mean that tribal communities could become restricted in their use of the Bight for subsistence and recreation purposes.

And how would any remediation work? Nobody knows since no one has ever attempted to clean up pollution that deep underwater.

Guo and Almada were thrilled by how many people wanted to participate in their workshop on the topic.

“The acceptances just kept coming,” said Guo. “In the end, we had over 80 people from 40 different groups and organizations participate in the workshop.”

The two-day workshop, held in July 2022, focused on defining research priorities in three areas: site characterization and management (that is, finding out how much DDT is present on the seafloor and where), potential impacts on human health and well-being as well as on the ecosystem and environment. Trained facilitators helped create a neutral space in which every attendee was encouraged to speak up. Additional listening sessions scheduled at a later date ensured that interested individuals who couldn’t attend the workshop were also heard.

“We intentionally tried to be very inclusive,” said Almada.

The workshop attendees flagged research questions important to their organization or community. For example, “if and how other environmental stressors such as warming temperatures, ocean acidification, harmful algal blooms and exposure to other contaminants might make DDT toxicity worse,” said Almada.

Following the workshop, USCSG, CASG and the State Water Board issued a call for proposals to encourage scientists to start researching the new underwater cache of DDT waste. This research will be funded by the State of California to match the amount ($5.6 million) appropriated by the federal government for studies on the San Pedro dump site.

The workshop also highlighted another critical issue: the need for collaboration.

“This is something we heard in almost every breakout session,” said Guo. “There are only a few groups that have the resources to send deep-sea robots 900 meters or more underwater. But there are existing archive samples of sediment, fish and other biota sitting in freezers and there are people who have the skills to work with them. There was this feeling of, how do we bring them together?”

The workshop report encourages the introduction of a “living database platform” which lists existing samples and active research projects to encourage collaborations as well as to avoid duplications.

The report also prioritizes which research questions should be tackled first.

“It’s a community-informed research agenda,” said Guo. “Having the community involved is important and we hope to continue some of the partnerships we have initiated.”

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.