This is the ninth in a yearlong series of stories showcasing the research that the Ocean Protection Council supported in partnership with California Sea Grant, with funding from Proposition 84.

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are something like a national park for the ocean: a space set aside where no harvest of fisheries is allowed. It’s proven that MPAs have positive impacts not just on biodiversity but on the abundance of fish harvested outside the protected areas. Might MPAs also help species weather the changes expected as the climate continues to warm?

Many commercially important fish species are at risk, since climate change will increase oxygen loss in the ocean (a condition known as hypoxia) and increase acidification. A recent study, funded by the Ocean Protection Council, examined whether MPAs might serve as refuges for species suffering from these changes. The hypothesis was that the persistence of “foundation” species might alter the environment sufficiently to buffer some of the projected chemical and physical changes.

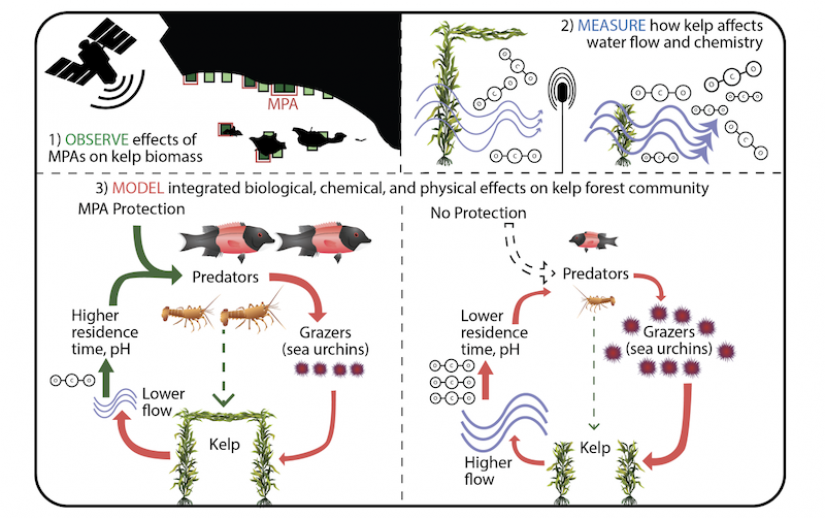

These are called “abiotic” changes since they’re not changes to living species. This study in question, led by Adrian Stier, a marine biologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, focused on giant kelp, which tends to persist at higher levels in MPAs in Southern California. This is a kind of trickle-down effect of the protected status: more predatory species like spiny lobster and sheepshead survive, which means there are fewer urchins to feed on the kelp. All that seaweed means that water flows through the MPAs more slowly. The presence of the kelp then alters the chemistry of the water through photosynthesis — which is a kind of antidote to the expected impacts of climate change. Photosynthesis consumes carbon dioxide, which lowers the water’s acidity, and releases oxygen.

The team — which included Kerry Nickols, a biologist at California State University Northridge, and three other UC Santa Barbara researchers, Gretchen Hofmann, Tom Bell and Nick Nidzieko — focused on eight MPAs between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. They used existing satellite imagery to estimate the amount of giant kelp growing across Southern California and other existing data to quantify the impact of this kelp on local biogeochemistry. Then, through laboratory studies, they examined how the observed physical and chemical changes were likely to impact the relationship between lobsters, urchin and kelp.

While results have not yet been published addressing the full hypothesis, the research has resulted in the publication of several papers on the food webs involving lobsters, urchins and kelp, including the impacts of warmer waters. One paper, for example, found that spiny lobsters better survive in warmer waters than had been previously known.

The team has been meeting with the California Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, suggesting that creating a “slot fishery” for spiny lobster — narrowing the range of sizes that can be harvested — would allow large lobsters to persist, and consume more urchins.