Water quality conditions in some parts of Morro Bay may be the key factor preventing eelgrass recovery after a recent decline, according to a new study published in the journal Estuarine, Coastal, and Shelf Science.

“The study shows that in many parts of the bay, environmental conditions likely limit eelgrass growth,” explains ecologist Jennifer O’Leary, who started investigating the eelgrass collapse as a California Sea Grant extension specialist based at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo. (O’Leary is now Africa Oceans Strategy Director with The Nature Conservancy).

Although researchers cannot yet pinpoint the cause of the initial eelgrass collapse, the study results could already help inform efforts to restore eelgrass in the bay by highlighting areas where restoration efforts could be successful.

“Eelgrass is important because it supports a range of marine life,” explains O’Leary. “It’s like the trees in a forest—these underwater plants provide food, structure, and shelter to many of the animals that live in the bay.”

A very special estuary

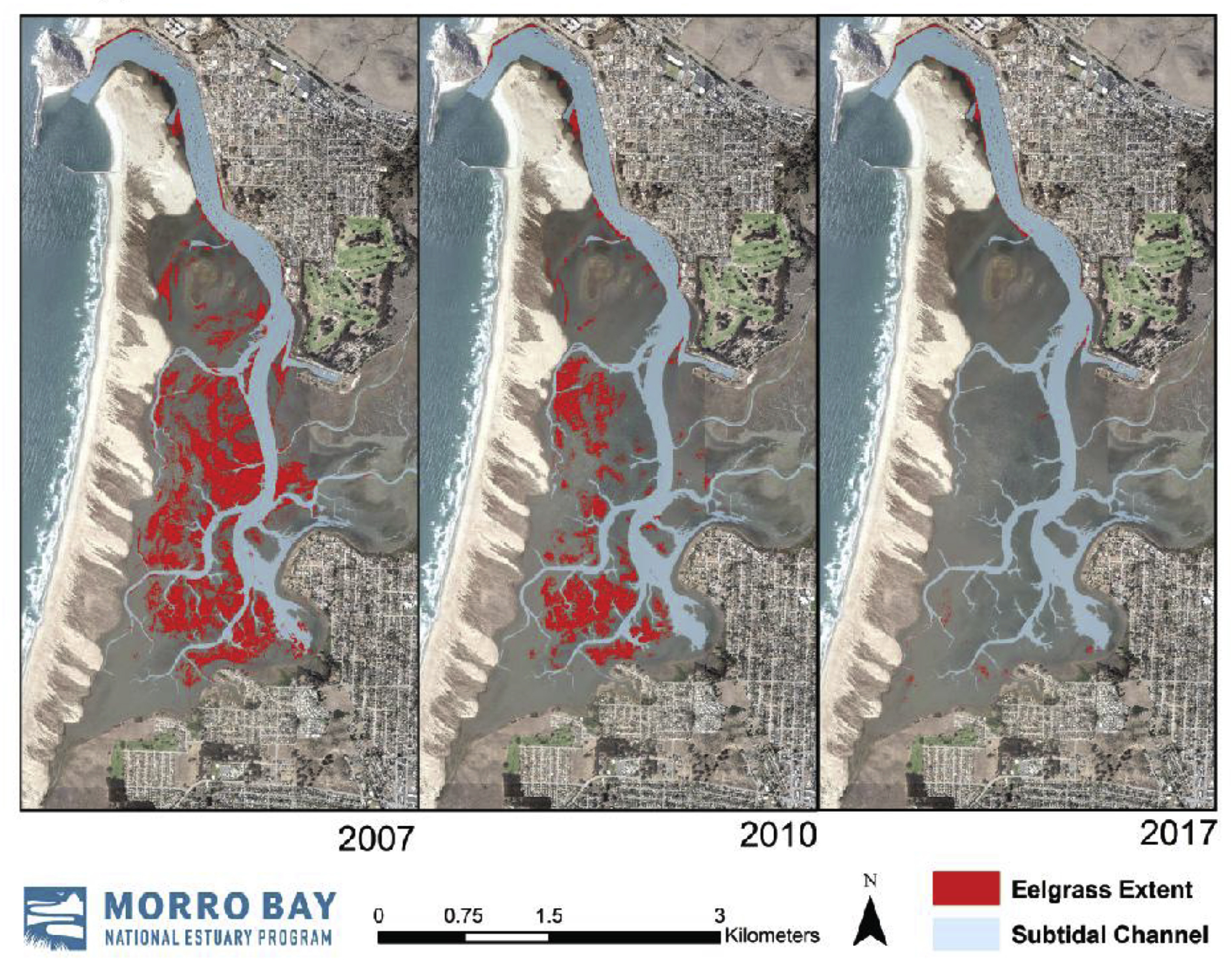

Morro Bay, a shallow estuary located on California’s central coast, just west of San Luis Obispo, is known for its natural beauty and wildlife, including sea otters and migratory Brant geese. But in recent years Morro Bay’s iconic eelgrass beds experienced a massive die-off, declining more than 90% since 2007. Efforts to restore the eelgrass have failed in many parts of the bay, and eelgrass is now only found close to the mouth of the bay and sporadically in other regions.

As a California Sea Grant extension specialist, O’Leary connected local, state, and federal partners, including the Morro Bay National Estuary Program (MBNEP), with an interdisciplinary team of scientists at Cal Poly to explore the problem. The MBNEP has tracked eelgrass health since the early 2000s and serves as a nexus in the community for the monitoring, restoration, and research surrounding eelgrass.

Led by Ryan Walter, physical oceanographer and physics professor at Cal Poly, along with his undergraduate student Edwin Rainville and O’Leary, the current study set out to analyze the hydrodynamics—the movement and characteristics of water in the bay, to understand how existing water quality conditions in different parts of the bay affect eelgrass survival. They set up oceanographic mooring stations underwater to measure a variety of water quality indicators at different sites in the bay in the summer of 2016. They also tracked down and analyzed hydrology, weather, dredging activity, and eelgrass data going back to the 1980s to gain a context of the eelgrass ecosystem.

The study shows that in areas where eelgrass disappeared and had not returned—particularly in the back part of the bay—water conditions were dominated by a combination of higher water temperatures and salinity, lower oxygen levels, high turbidity that limits light availability, and limited flushing—that is, water gets “trapped” for longer periods of time. Previous research has shown that all of these factors can be stressors for eelgrass, and together, they may be preventing eelgrass from bouncing back.

Close to the mouth of the bay, where ocean tides regularly refresh this region with relatively cool, clear, and more oxygenated water, the researchers found that eelgrass has persisted, and recent restoration efforts with the MBNEP were successful.

A canary on the coastline

Walter and O’Leary are still working to establish the cause of the initial decline. The study results support the idea that sediment changes in the bay—driven by some combination of dredging, heavy precipitation, and sediment loading events, followed by drought years—may have contributed to the decline, a hypothesis that they are now exploring as part of a California Sea Grant-funded research project with numerical modeling specialist Sean Vitousek from the University of Illinois at Chicago and the MBNEP.

“Eelgrass is a critical component of a healthy, functioning Morro Bay ecosystem. One of the Morro Bay National Estuary Program’s highest priorities is to address eelgrass loss through monitoring, restoration, and research. The efforts under the Sea Grant project will be invaluable in discerning reasons for the loss and helping determine the best way forward as we work to protect and restore this crucial habitat,” says MBNEP Executive Director Lexie Bell.

The new study also highlights the need for more research and monitoring of similar estuaries, both in California and beyond to establish baselines to better assess drivers of ecosystem collapse when they occur. While there were no comprehensive measurements prior to the decline, current monitoring in the bay is supported by Walter’s grant from the Central and Northern California Coastal Ocean Observing System (CeNCOOS) (for a near-real time view of measurements, visit the CenCOOS Morro Bay Shore Station webpage)

“Morro Bay is a relatively short estuary that, like many other estuaries in California and Mediterranean climates, receives very little freshwater input during large portions of the year,” explains Walter. This means that different parts of the bay rely on the tides to flush and exchange the water in different parts of the bay during the summer dry season. This is in contrast to other estuaries that have persistent freshwater input from rivers throughout most of the year that drive exchange of water throughout the estuary. Moreover, Morro Bay also has a long history of dredging, and has experienced eelgrass declines in the past, though never to this extent.

“Low inflow estuaries like Morro Bay may be more vulnerable to sudden ecosystem changes like the eelgrass collapse we observed here,” says Walter.