On my third day as a California Sea Grant State Fellow at Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary (CINMS), I was thrust into the first meeting of a community-based working group that was addressing some of the most complex marine issues in the region. I was stoked! This was, after all, one of the main reasons that I applied to be a fellow: so that I could better understand how communities are engaged in public processes, and so that I could see how creative environmental problem solving happens on the ground.

At the first meeting, I realized the Marine Shipping Working Group was really going to have to get creative to address their four goals:

- Reduce the risk of ship strikes on endangered whales;

- Decrease air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from ships;

- Improve navigational safety and promote efficient maritime shipping; and

- Reduce conflicts among ocean users.

Right off the bat, there was contentious discussion of the working group’s goals, deciding how they should be worded, and if they should be prioritized. There was tension in the room, and it’s not surprising when you really consider the challenges that this diverse group of stakeholders was facing. Imagine this: thousands of whales and thousands of ships visit the region around CINMS every year, becoming part of a dynamic marine environment that includes a national marine sanctuary, a national park, several major fisheries, a Navy missile testing range, some of the biggest commercial ports in the world, and thousands of recreational boaters, divers, and tourists.

All of this occurs in a major marine biodiversity hotspot, which is caused by the unique confluence of cool and warm currents at the Channel Islands. Neighboring this marine environment are the populous Santa Barbara, Ventura, and Los Angeles counties, where thousands of ocean users reside, and where air pollutants from large container ships are carried onshore by prevailing winds.

The region around Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary is heavily transited by large commercial vessels traveling into and out of the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles (two of the nation’s busiest ports). This region is also a hotspot for blue, fin, humpback, and gray whales. One of the working group’s goals is to reduce the risk of ship strikes on endangered whales.

Photo: John Calambokidis/Cascadia Research

Although the challenges on the table appeared colossal, the Marine Shipping Working Group process had been set up for success. Professional facilitators were there to guide productive discussions, an online collaborative mapping tool (SeaSketch) was loaded with the best available science, and all of the key players were at the table. The working group consisted of representatives from the U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Coast Guard, Channel Islands National Park, NOAA Fisheries, Marine Exchange of Southern California, shipping industry, air pollution control district, and the tourism, research and conservation communities. As you can imagine, all of these groups have very different perspectives and values, so the first step was to initiate conversations that would allow working group members to begin to understand each other’s worlds.

The Marine Shipping Working Group convened in person four times and had six webinars from February 2015 – January 2016.

The Marine Shipping Working Group convened in person four times and had six webinars from February 2015 – January 2016.

Photo: Grace Goldberg/UCSB

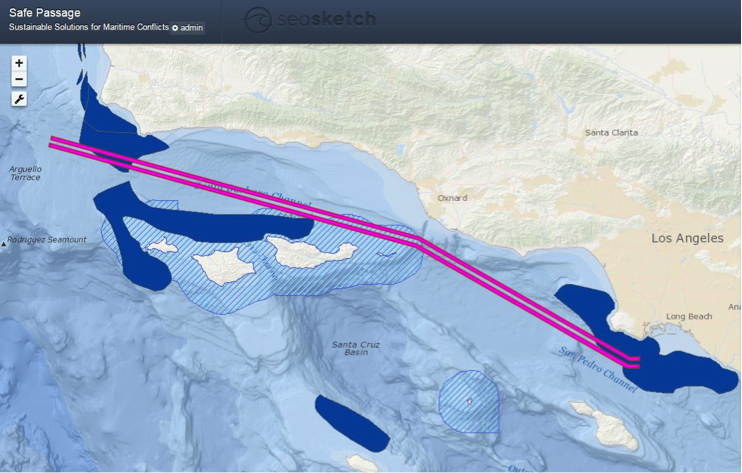

Over the course of ten months, an incredible amount of information was shared and discussed. The group debated the pros and cons of different management options, and designed some of their spatial ideas in SeaSketch. For example, working group members could go into SeaSketch and display whale habitat maps and then design new routing measures with the goal of moving ship traffic away from high density whale areas. The group considered a wide range of management, outreach, education, and research ideas; everything from whale detection with infrared cameras to vessel speed reduction zones. As these ideas were put on the table, it became clear that there were some options that some working group members would simply not support. For example, some working group members were proponents of vessel speed reduction zones, because ships produce fewer emissions and are less likely to cause a fatal ship strike when they transit at slower speeds. However, other working group members did not support vessel speed reduction, because it reduces maritime shipping efficiency. This was just one of the many sticking points that rose to the surface during the process.

Working group members used SeaSketch, a collaborative ocean planning platform, to bring the best available science into the conversation. Shown here are just a few layers available in SeaSketch: Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary boundaries (blue hatch), the existing shipping lanes in the Santa Barbara Channel (pink), and biologically important feeding areas for blue whales[1] (dark blue).

Morgan Visalli, 2015 Sea Grant Fellow at CINMS, displaying SeaSketch on the projector screen during the fourth Marine Shipping Working Group meeting in October 2015.

In January 2016, at the final meeting, the group had to decide what they would include in their final packet of recommendations that would be forwarded to the CINMS Advisory Council and then to the Sanctuary Superintendent. By this point, they had come to accept that they didn’t have a silver bullet; that there is no one solution for their problems. Rather, what they had produced was a menu of more than fifteen management, research, education, and outreach ideas. Each option had its own promise to achieve some of the group’s goals, as well as its own pros, cons, and level of support from the group.

At that last meeting, I looked around the room, and wondered if the group felt defeated by the lack of consensus. It’s tough to come to the end of a year of hard work and feel as though the issues are still partially unresolved. It was then that one of the co-chairs of the working group spoke up, and changed my outlook on the outcome of the process. She eloquently reminded us to not lose sight of what had been gained over the past year: new relationships and expanded understandings of each other’s perspectives, which are essential when working on complex, long-term challenges. She reminded us to consider the Marine Shipping Working Group within the context of a multinational shipping industry and a global ocean. People all over the world are struggling with similar problems, and many working group members will continue to work on these topics for years to come. And now they have a deeper understanding of the issues, can comprehend each other’s perspectives, and know how to communicate with stakeholders that have very different values from their own.

Written by Morgan Visalli

[1] Calambokidis, J., Steiger, G. H., Curtice, C., Harrison, J., Ferguson, M., Becker, E., DeAngelis, M., & Van Parijs, S. M. (2015). 4. Biologically important areas for selected cetaceans within U.S. waters –West coast region. In S. M. Van Parijs, C. Curtice, & M. C. Ferguson (Eds.), Biologically important areas for cetaceans within U.S. waters (pp. 39-53). Aquatic Mammals (Special Issue), 41(1). 128 pp.