Pacific Shortfin Mako

Isurus oxyrunchus

The Science

THE SCIENCE

With top speeds of 43 mph, the shortfin mako is one of the fastest sharks on the planet! [19]

Taxonomic description

- Highly migratory shark with a pointed snout, long gill slits and conical sharp teeth which protrude forward from the jaw, making it visible when its mouth is closed. [1]

- Mature individuals can reach four meters, although the average size is 1.5-1.7 m. [1]

- Has counter-shaded fusiform shapes and lunate tails, making it one of the fastest pelagic predators with a top speed of 43 mph (70 km/hr). [1,19]

Distribution

- Can be found worldwide from temperate to tropical waters. [6]

- In the United States, this shark can be found in temperate waters from southern Baja California to the southern Washington coast. [7]

- A small number have been caught across the Pacific in Japan and Taiwan. [7]

Life history

- Equipped with countercurrent exchangers that let the shark maintain internal temperatures several degrees above ambient water. [2]

- Regional endothermy enhances its muscle and digestive performance and lets the shark exploit cooler temperatures where ectothermic prey is sluggish. [3]

- Diet studies off the California coast show the sharks feed primarily on jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas), Pacific saury (Cololabis sara), Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax), Pacific chub mackerel (Scomber japonicas), tuna (Thunnus spp.), other sharks and marine mammals. [4]

- Has a slow growth rate, late age of maturity, low fecundity, and can live to 30 years old. [5]

- Males reach maturity at eight years old while females become reproductively active at twenty years of age. [5]

- Once it reaches maturity, their eggs are internally fertilized and develop within the mothers for 15-18 months. [5]

- Each female will give birth to 4-15 live pups once every three years. [5]

Habitat

- Genetic data suggest a single population across the North Pacific. [8]

- Electronic tagging data suggest horizontal movements are dependent on seasonal oceanographic factors that vary across maturity level. [6]

- In the summer months, this shark tends to concentrate in the California Current and moves offshore in the winter and spring months. [6]

- The Southern California Bight (SCB) appears to be a particularly important habitat for juveniles with a higher proportion of young sharks, suggesting the SCB could be a productive nursing area. [9]

- Vertical movements vary both within and among individuals. [9]

- Spends most of its time in the top 50 m of the water column but frequently dives below the thermocline to forage, navigate, and conserve energy. [9]

The Fishery

THE FISHERY

Despite its role in worldwide pelagic fisheries, key fishery information is lacking, including data on catch and finning on the high seas. [20]

Seasonal availability

- The U.S. West Coast recreational fishery is open year-round and allows the take of two fish per day with no size limit.

- Commercially, makos are caught as incidental take by the U.S. high-seas longline and California drift gillnet fisheries which operate year-round and mid-August through January, respectively.

- Drift gillnet fishing is prohibited in the Leatherback Conservation Area Closure from August 15 to November 15. [10]

Regulatory and managing authority

- Internationally overseen by the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). [11]

- Along the Pacific West Coast, the fishery is overseen by NOAA fisheries and, as established by the Magnuson-Stevens Act, the Pacific Fishery Management Council through the West Coast Highly Migratory Species Fisheries Management Plan. [10,11]

- As established by the Marine Life Management Act, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) collects data on this fishery through the Pelagic Fisheries and Ecosystems Program. [21,22]

- Protections created by the Shark Conservation Act inform regulations specific to this fishery. [11]

Gear type

- Mainly caught as incidental catch with drift gillnets and on hook-and-line in California. [12]

- Drift longline gear is used for the international fishery outside of Exclusive Economic Zone. [12]

Status of the fishery

- A 2018 integrated population model for mako sharks in the North Pacific indicated that mako sharks are not being overfished. [13]

- Information about current landings and revenue for mako sharks is available through the Pacific Fishery Management Council. [14]

Potential ecosystems impacts

- In the U.S., generally caught from interactions within the well-managed U.S. longline and California drift gillnet fisheries at low numbers. [13]

- There do not seem to be significant ecosystem impacts on the west coast population because there is no primary mako fishery and landings are low. [15]

- Other countries with less managed fisheries could have a greater risk of depleting the stock due to the mako's slow growth rate, late age of maturity, and low fecundity. [16]

- Domestic longline and drift gillnet fisheries have little impact on the ecosystems but under-regulated high seas counterparts could have significant bycatch of protected species. [16]

The Seafood

THE SEAFOOD

While targeted for its high quality meat, vitamin-rich oil, and edible fins, it is also valued for non-food uses of its hide, jaws, and teeth. [20]

Edible portions

- The meat and fins can be consumed. [20]

Description of meat

- The mako shark's energetic life history produces high-quality meat. [17]

- The meat is typically sold as boneless steaks resembling swordfish but it is illegal to possess the fins in the U.S.

- Mako shark steak has a slightly sweet, meaty taste.

- Both the taste and the texture of mako is similar to swordfish but the meat is moister.

- Raw mako is soft and ivory pink that turns white and firm when cooked.

- To ensure the meat is mako, look for sandpaper-like skin and flesh without the whorls characteristic of swordfish steak.

Culinary uses

- Mako's similar taste and texture profile to swordfish allows chefs to substitute one for the other.

- The versatile, hearty meat can be grilled, blackened, seared, or enjoyed in any way swordfish is prepared.

- For a recipe for grilled shark steaks, visit The Spruce Eats. [23]

- For a fried Mako shark recipe, visit cdkitchen. [24]

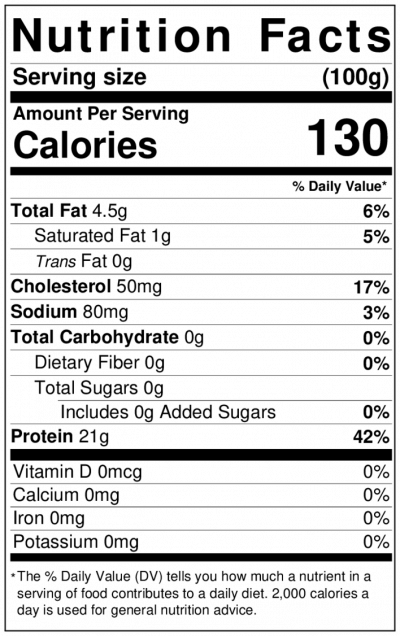

Nutritional information

- Nutrition facts for 100g of mako shark are on the table to the right. [15]

Toxicity report

- Has urea in its bloodstream and must be bled and iced immediately to prevent the urea in their tissues from turning into ammonia. [18]

- Other known toxins include mercury and PCBs, although studies so far have shown that juvenile sharks contain low amounts of mercury. [18]

Seasonal availability

- The U.S. longline fleet operates year-round but they land their fish in Hawaii during the spring and summer and in California during the fall and winter.

- California drift gillnet is most active in the fall.

References

[1] Vetter, R., Kohin, S., Preti, A. N. T. O. N. E. L. L. A., Mcclatchie, S. A. M., & Dewar, H. (2008). Predatory interactions and niche overlap between mako shark, Isurus oxyrinchus, and jumbo squid, Dosidicus gigas, in the California Current. CalCOFI Report, 49, 142-156.

[2] Sepulveda, C.A., Kohin, S., Chan, C. et al. Movement patterns, depth preferences, and stomach temperatures of free-swimming juvenile mako sharks, Isurus oxyrinchus, in the Southern California Bight. Marine Biology 145, 191–199 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-004-1356-0

[3] Watanabe, Y. Y., Goldman, K. J., Caselle, J. E., Chapman, D. D., & Papastamatiou, Y. P. (2015). Comparative analyses of animal-tracking data reveal ecological significance of endothermy in fishes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(19), 6104-6109. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1500316112

[4] Preti, A., Soykan, C.U., Dewar, H. et al. Comparative feeding ecology of shortfin mako, blue and thresher sharks in the California Current. Environ Biol Fish 95, 127–146 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-012-9980-x

[5] Ribot-Carballal, M. C., Galvan-Magaña, F., & Quiñonez-Velazquez, C. (2005). Age and growth of the shortfin mako shark, Isurus oxyrinchus, from the western coast of Baja California Sur, Mexico. Fisheries Research, 76(1), 14-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2005.05.004

[6] Nasby-Lucas, N., Dewar, H., Sosa-Nishizaki, O. et al. Movements of electronically tagged shortfin mako sharks (Isurus oxyrinchus) in the eastern North Pacific Ocean. Anim Biotelemetry 7, 12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-019-0174-6

[7] Wells, R. J., Smith, S. E., Kohin, S., Freund, E., Spear, N., & Ramon, D. A. (2013). Age validation of juvenile shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) tagged and marked with oxytetracycline off southern California. Fishery Bulletin, 111(2), 147-160. 10.7755/FB.111.2.3

[8] Michaud, A., Hyde, J., Kohin, S., & Vetter, R. (2011). Mitochondrial DNA sequence data reveals barriers to dispersal in the highly migratory shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus). In Report of the Shark Working Group Workshop. Annex (Vol. 4). Web. http://isc.fra.go.jp/reports/shark/shark_2011_2.html. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

[9] Peter Klimley, A., Beavers, S.C., Curtis, T.H. et al. Movements and Swimming Behavior of Three Species of Sharks in La Jolla Canyon, California. Environmental Biology of Fishes 63, 117–135 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014200301213

[10] Pacific Fisheries Management Council. n.d. Fishery management plan and amendments. Web. https://www.pcouncil.org/fishery-management-plan-and-amendments-4/. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

[11] Fishwatch. 2020. Pacific Shortfin Mako Shark. Web. https://www.fishwatch.gov/profiles/pacific-shortfin-mako-shark. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

[12] Taylor, V., Bedford, D. 2001. California’s Living Marine Resources: A Status Report: Shortfin Mako Shark. California Department of Fish and Game. California, USA. Web. https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=34347&inline. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

[13] ISC (2018). Stock Assessment of Shortfin Mako shark in The North Pacific Through 2016. Annex 15 in Plenary Report of the International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North Pacific Ocean. Web. http://isc.fra.go.jp/reports/isc/isc18_reports.html. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

[14] Pacific Fisheries Management Council. 2017. Summaries of Commerical Fishery Catch, Revenue, and Effort (Pacfin data). Web. https://www.pcouncil.org/summaries-of-commercial-fishery-catch-revenue-and-effort-pacfin-data/. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

[15] Campana, S. E., Joyce, W., Fowler, M., & Showell, M. (2015). Discards, hooking, and post-release mortality of porbeagle (Lamna nasus), shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus), and blue shark (Prionace glauca) in the Canadian pelagic longline fishery. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 73(2), 520-528. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsv234

[16] Northridge, S., Coram, A., Kingston, A., & Crawford, R. (2017). Disentangling the causes of protected‐species bycatch in gillnet fisheries. Conservation Biology, 31(3), 686-695. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12741

[17] Seafood Source. 2014. Shark, Mako. https://www.seafoodsource.com/seafood-handbook/finfish/shark-mako. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

[18] Biton-Porsmoguer S, Bǎnaru D, Boudouresque CF, et al. Mercury in blue shark (Prionace glauca) and shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) from north-eastern Atlantic: Implication for fishery management. Mar Pollut Bull. 2018;127:131-138. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.12.006

[19] Díez G, Soto M, Blanco JM. Biological characterization of the skin of shortfin mako shark Isurus oxyrinchus and preliminary study of the hydrodynamic behaviour through computational fluid dynamics. J Fish Biol. 2015;87(1):123-137. doi:10.1111/jfb.12705

[20] Rigby, C.L., Barreto, R., Carlson, J., Fernando, D., Fordham, S., Francis, M.P., Jabado, R.W., Liu, K.M., Marshall, A., Pacoureau, N., Romanov, E., Sherley, R.B. & Winker, H. 2019. Isurus oxyrinchus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T39341A2903170. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T39341A2903170.en. Accessed 9 Sept 2020.

[21] Marine Life Management Act. n.d. California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Web. https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Marine/MLMA. Accessed 24 August 2020.

[22] Overview of the Pelagic Fisheries and Ecosystems Program. n.d. California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Web. https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Marine/Pelagic#52132542-overview. Accessed 9 December 2020.

[23] Riches, D. The Spruce Eats. 2020. Grilled Shark Steaks. Web. https://www.thespruceeats.com/grilled-shark-steaks-334426. Accessed 19 January 2021.

[24] cdkitchen. n.d. Fried Mako Shark With Wild Rice and Wine. Web. https://www.cdkitchen.com/recipes/recs/811/FriedMakoSharkWithWildRic696…. Accessed 19 January 2021.

[25] Tuna Harbor Dockside Market. 2017. Digital image. Web. https://www.facebook.com/thdocksidemarket/photos/1918693708159903. Accessed 22 February 2021.

[26] Conlin, Mark. NOAA NMFS SWFSC Large Pelagics Program.

[27] Heim, Walter. NOAA/SWFSC