Why do people harvest local seafood despite known health risks?

This project contributes to our knowledge of the risks associated with self-harvested seafood in San Diego Bay by looking closely at the bay's food resources (shellfish and finfish) and the people who harvest them. Our work leverages recent and continuing consumption and contamination studies, and focuses on the following objectives:

- What shellfish are available in the bay? Determine the types and abundances of publicly accessible shellfish and their biological and chemical contaminant risks.

- Who harvests seafood from the bay, and why? Determine who is harvesting seafood from the bay (including demographics and use patterns), and why (cultural, economic, and health-related factors).

- How can we better manage the bay's resources? Collaboratively develop ecologically- and culturally-based seafood consumption information to inform harvest and consumption decisions, and contribute to broadening stakeholder discussions about the future of San Diego Bay.

Cultural, economic, and public health determinants of social vulnerability to seafood contaminants in an urban embayment in Southern California

People from coastal urban centers around the world harvest and consume seafood from local embayments despite growing recognition that this seafood contains chemical and biological contaminants that pose human health risks. People who harvest despite known risks include those in extreme poverty who subsistence fish, but recent evidence also reveals that many fish consumers live above established poverty lines.

This project will contribute to a better understanding of the risks associated with self-harvested seafood in San Diego Bay and beyond. In particular, this project will: Establish a baseline assessment of shellfish availability, risk and consumption patterns for San Diego Bay that is similar to, but scaled-down from, the intensive finfish consumption assessments that exist for San Diego Bay; and second, improve our understanding of the cultural worlds of anglers who were identified in previous finfish consumption studies as continuing to fish despite known health risks and economic need.

The researchers will work with entities associated with the San Diego Bay and other interested parties to disseminate and translate the research for use with their public outreach, environmental management, and space planning efforts for the bay.

Results from recent investigations into shellfish resources in San Diego Bay

We already know a lot about the finfish that are commonly caught in San Diego Bay, including information about the types and amounts of bay fish that are safe to consume (see OEHHA advisories for San Diego Bay here; see a recent study on San Diego Bay anglers here). But, there is still a lot to learn about the bay's shellfish resources.

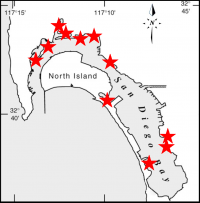

In July 2018 and January 2019, our team conducted rip rap surveys in 11 publicly-accessible locations throughout the bay (between -1 and 3 ft above MLLW) to determine what types of shellfish are available to potential harvesters along the waterfront. We also collected oysters from each of these sites that will be analyzed for contaminants, so we can better understand the potential risks of consuming shellfish from the bay.

Species richness (number of species) was highest at the two Shelter Island sites, Embarcadero, and Harbor Island (12-16 species per site), while the other seven sites were each populated by 3-8 species. Most of these species would likely not be of interest to harvesters for food, however some are of interest for other uses, such as bait (e.g., lined shore crabs).

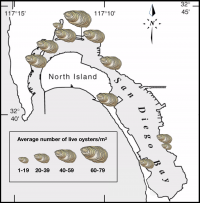

Of the species found in our sites, Pacific and Olympia oysters and Mediterranean mussels are the three species that would likely be of the most interest for food harvest. Oyster density ranged from an average of 10-63 oysters/m2 at each site (see figure below). Mussels were less abundant, with most sites featuring an average of <1 mussel/m2, and only 2 sites (the Shelter Island sites) with abundances close to (or surpassing) those of oysters (28/m2, 112/m2).

As we talk to people about their seafood harvesting habits on piers throughout the bay, we are also conducting pier trapping surveys with hoop nets, to understand what shellfish species are available to pier anglers. Stay tuned for further information on shellfish availability and contamination in the bay!

Results of recent interactions with recreational pier fishers in San Diego Bay

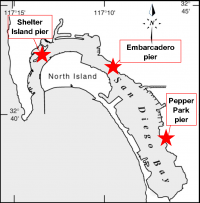

From the summer of 2018 through the spring of 2019, our team (photos at the bottom of this page) frequently visited three public fishing piers in San Diego Bay - Shelter Island, Embarcadero, and Pepper Park (see map) - to survey seafood harvesters in order to get a sense of the motivations behind seafood harvest in the bay.

Patterns of Fishing

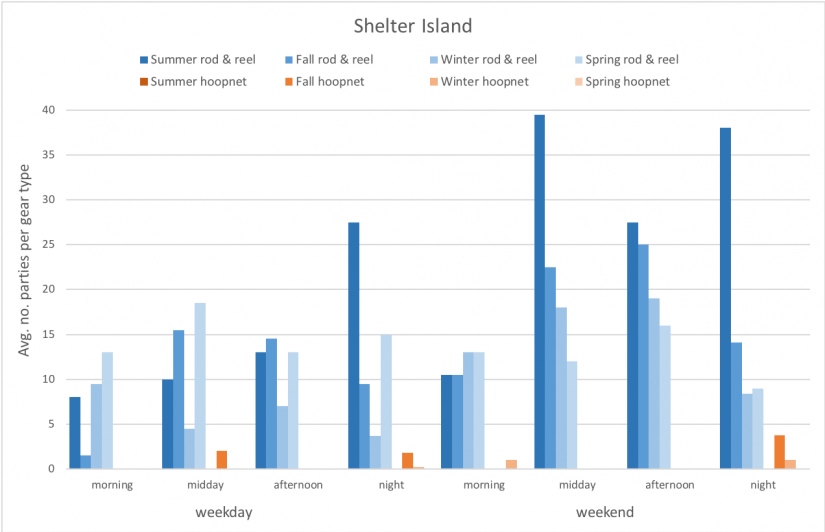

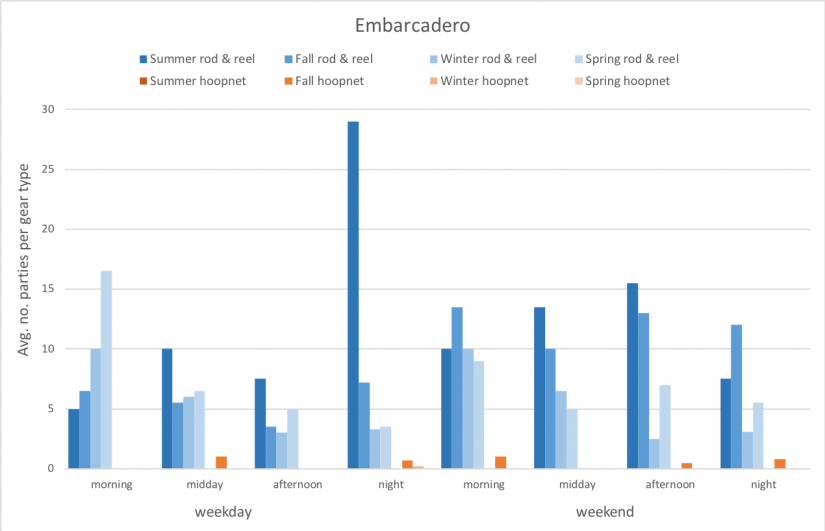

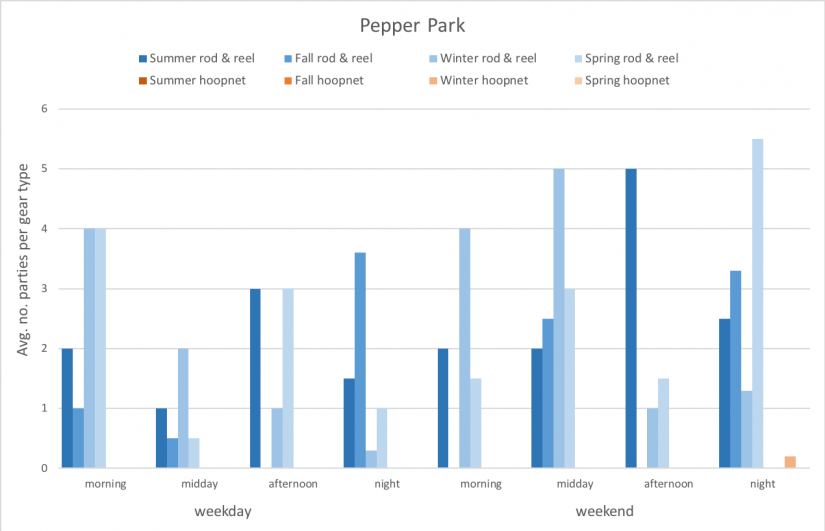

The majority of the fishers we encountered were using rod and reel to catch fish (see graphs below). Much less common, yet of interest to us, were shellfish harvesters, most of whom primarily targeted California spiny lobster using hoopnets. Of the 61 shellfish harvester interviews we conducted, 50 were from the Fall, during the first few months of recreational lobster season (September 29, 2018 - March 20, 2019).

Shelter Island Pier was the most popular for lobster hoopnetting, followed by Embarcadero and Pepper Park, where we only encountered one hoopnetter during our year of surveying (see graphs below). Hoopnetting usually occurred at night and was generally more popular in the Fall (vs. Winter), closer to the start of lobster season. On average, hoopnetting parties consisted of 1-2 people, with a total of 1-2 nets per party.

Hoopnetters were always outnumbered by rod and reel fishermen, who were most active in the Summer (least in Winter), and on weekends (vs. weekdays). On average, rod and reel fishing parties consisted of about 2 people, with a total of 2-3 rods per party.

Stay tuned for more information on the results of our surveys with shellfish harvesters!

Project partners:

Physis Environmental Lab

San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board

Ocean Discovery Institute

Dimitri Deheyn at UCSD Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Michael Baker at UCSD School of Medicine

David Pedersen

David Pedersen

Theresa Sinicrope Talley

Theresa Sinicrope Talley