New research from California Sea Grant explores people’s motivations for fishing and eating catch from San Diego Bay, despite well-known health risks. Understanding these underlying meanings could help to craft more effective and socially-tailored consumption and health guidelines.

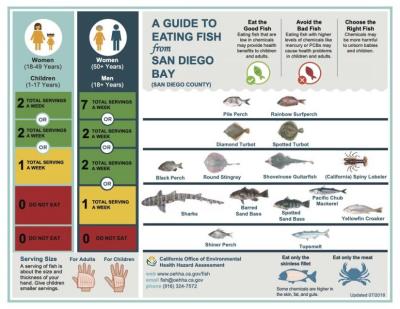

A recently published study by Pedersen and his colleagues found that contaminants in San Diego Bay are being circulated throughout the food web, posing health threats to people fishing recreationally in the area. But in order for waters to be properly managed for this health risk, it’s important to understand why people are fishing in the first place — what is the significant social meaning of that practice?

David Pedersen, an anthropologist at the University of California San Diego, took the lead on this inquiry, which he titled “Fishing for Meaning.” What he found was that even though some of these fish may pose a health risk, the practice of fishing for and eating seafood out of San Diego Bay is a life-enriching activity.

Previous research into recreational fishing in San Diego Bay included limited exploration of why people were fishing, but did state that very little of it was “subsistence fishing” — fishing for food to help meet nutritional needs. Pedersen also had a suspicion that nutritional value was only part of the bigger picture.

“Fish mean much more than just calories or protein,” Pedersen says.

To collect data over the course of eight months between two popular fishing piers in San Diego Bay, Pedersen used a “practices of meaning” approach, something that was developed at the intersection of history and anthropology. This approach posits that “meaning-making is a practical activity.”

“There's a code or system that everyone works within,” Pedersen says. “The code only exists because we constantly reproduce it — which also means we can change it — even as it also reacts upon us in real ways.”

In other words, the practice of fishing may culturally signify important things about who we are as people, what we believe and how those things come to be.

Pedersen’s anthropological data collection went beyond the practice of surveying with a clipboard. He used a method called “participant observation,” which is when a researcher not only collects responses from individuals engaging in an activity but engages in that activity themselves. Pedersen was always open and forthright about who he was and why he was asking questions, but by participating in fishing himself, he was able to enter into the world of his responders.

“By being there fishing, it also shows that part of me is committed to the same activity that everyone is involved in,” Pedersen says.

Doing both the observation and the participation is a bit of a juggling act. For some people Pedersen met, it sparked their curiosity, and for others, it made them shy away from further questions.

“For me, it's a constant balancing act between the participation part and the listening and looking and the questioning — the observation part.”

During analysis of the responses, Pedersen noticed five main through-lines or themes regarding the social and cultural motivations of pier anglers. First, is what he calls the practice of provisioning — recreationally fishing in San Diego Bay to augment one’s diet.

Just as important was family formation and maintenance. While spending time on the piers, Pedersen encountered various family assemblies that spanned generations. The primary drivers were youth socialization or elderly care. Many guardians wanted to make sure their kids had the experience of fishing or spending time with their elders. In many cases, fishing from the pier was something the whole family could enjoy doing together and was more affordable than other group activities such as going out to a movie.

“Regularly, these were very caring adults who wanted to provide a certain kind of experience for the children that they were looking out for,” Pedersen says.

Another theme Pedersen identified was work-capacity replenishment. Many people he encountered on the piers seemed to tie their ability to work throughout the week directly to this kind of outlet. This leisure activity that allowed people the opportunity to be out in what they regularly referred to as “nature” gave them the energy to keep working.

“You need to have time to rest and recuperate from work,” Pedersen says. “And we know that if this is not adequately allowed, crisis erupts.”

In this way, recreational fishing significantly complements the economy.

Another theme, human subject formation, involves the way in which people interact with the fish, and how it may be similar or different from the ways people interact with other humans.

“It's setting up boundaries that you cross and boundaries that you uphold between human and non-human,” Pedersen says.

Pedersen's last theme was related — affective dispositions was the discussion people had regarding the proper way to feel and act with respect to fish. In this way, the simple act of fishing contributed to shaping emotional habits among the people present. People were practicing how, when and why to feel in particular ways.

All five of these themes identified by Pedersen fall within the general process that scholars call socialization or “social reproduction” — how social groups organize and maintain themselves.

When it comes to contaminants and health risks, some people just didn’t want to hear about it. It seemed that they already knew there was some risk associated with consuming local bay seafood, but individuals had deemed that risk acceptable in exchange for the social benefits they got from harvesting and eating those fish.

What this tells researchers is that when people fish for seafood in the San Diego Bay despite potential health risks, it often isn’t because of a knowledge gap. It’s likely because fishing and eating fish provide many social and emotional benefits that people find necessary and worthwhile. This information is key for effective management of contaminants and seafood moving forward.

“In a way, what we're talking about is two different meanings of the fish,” Pedersen says. “One meaning of seafood is that it's dangerous. And another meaning is that it is life-affirming.”

Furthermore, these two meanings are impossible to separate from each other. Because of the interwoven, multifaceted characteristics of the issue, a comprehensive approach to management is necessary. To do this right, says Pedersen, a multidisciplinary course of action is important. It’s not only the health issues, it’s the social implications as well. In this way, the social significance of fish can help inform effective management.

“If we appreciate that these two meanings of seafood are co-produced within the overall system … that means that the solutions are difficult,” Pedersen says. “We can't choose one or the other. They're both products of the same sort of socio-natural system that is greater San Diego.”

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.