Good news: The oysters in Elkhorn Slough are having babies again. For the first time in over a decade, researchers last fall found wild juvenile oysters in the tidal estuary 100 miles south of San Francisco. The discovery came after conservationists outplanted close to 200,000 oysters grown in a pioneering conservation aquaculture project.

Elkhorn Slough, which extends inland for seven miles in the middle of Monterey Bay, used to host plentiful Olympia oysters (Ostrea lurida) or “Olys”, the West Coast’s only native oyster species. “Indigenous people harvested them here sustainably for millennia,” says Kerstin Wasson, Research Coordinator at the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve. Wasson’s Olympia oyster restoration project was funded by the California Ocean Protection Council, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and received support from California Sea Grant.

Vanishing oysters

Pollution, a lack of tidal exchange due to human-built levees and overharvesting as California’s population grew have ravaged Olympia oyster populations. It’s a fate they share with other oyster species. Globally, an estimated 85% of natural oyster reefs have vanished over the past century, surpassing the decline in coral reefs.

And while some aquaculturists grow oysters along California’s coast, they cultivate non-native species such as the Pacificoyster (Crassostrea gigas), which was introduced from Asia, due to its faster growth and bigger size.

By 2018, Elkhorn Slough’s Oly population had plummeted to fewer than a thousand, distributed along the seven miles of this backwater. Reproduction ceased. Oysters spawn into the water, and at such low densities, their sperm becomes too diluted before it reaches another oyster, says Jacob Harris, who participated in the project as a master’s degree candidate at the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories of San Jose State University (MLML) in Monterey Bay. “Because oysters can’t move they must rely on oysters nearby to fertilize their eggs.”

Starting in 2012, researchers surveying the slough had become unable to find juvenile oysters. And those mollusks they did encounter were growing old. “Most oysters probably don't even live six years, so local extinction was becoming a real danger,” says Wasson.

Using aquaculture to aid conservation

Deciding that the slough’s Olys should not disappear on her watch, Wasson reached out to California Sea Grant Extension Specialist Luke Gardner, who is based at MLML, with an ambitious proposal: to establish the first conservation aquaculture project for oysters in California.

Conservation aquaculture uses the same basic techniques as commercial aquaculture, which today grows about half of the globally consumed seafood. This makes some conservationists uneasy.

Opponents fear that rearing wild species in captivity, even for restoration, can reduce genetic diversity since often only a small portion of a population is propagated. Such reduced genetic diversity can make a population more vulnerable to changes in the environment or climate.

However, proponents argue that, if done well, the approach can help endangered fish and mollusks recover. White sturgeons and white abalone are among the species that have gotten a boost from restoration aquaculture in recent years. “The metaphor we use is greenhouses, in which you grow native plants,” says Wasson. “We collect seeds from wild plants, we grow them in the greenhouse, then we plant them out.”

"We turned the lights down low, maybe added some music, and the oysters spawned."

In 2018, Moss Landing researchers started going to Elkhorn Slough once a year to “borrow” several hundred mature oysters on average from different locations and take them to the hatchery facility.

“We turned the lights down low, maybe added some music, and the oysters spawned,” jokes Harris. Once baby oysters had hatched, they were pampered in tanks until they had grown to about the size of a dime, then returned to the slough, alongside their oyster parents. “We get different broodstock every year to diversify the cohorts as much as possible,” says Ava Salmi, California Sea Grant staff research associate and MLML’s lead technician for the project.

In the first year, the team outplanted around 10,000 baby oysters. By last year, that number had grown to 162,500. “More than in all previous years combined,” says Gardner.

Giving baby oysters a perch above the mud

Partly this became possible because the team recently bought two new bioreactors from Industrial Plankton, in which to grow the microalgae that baby oysters eat several times a day. “Oysters require a bunch of different algae to get everything they need. It’s the hardest part about running a hatchery for them,” says Gardner. The complicated set-up relies on filtered water, LED grow lights and ultraviolet sterilizers to fight ever-present bacterial diseases. The two new bioreactors automate the process.

The outplanting, too, required strategizing. Oysters grow in rocklike reefs that provide habitats for other invertebrates and young fish. But after decades with few oysters, Elkhorn Slough’s bottom has turned into a soft, “organic goop,” as Wasson calls it. What causes the goop are massive algal mats that — fertilized by farm runoffs — now grow in the estuary, then die. “There’s two feet of chocolate mousse mud on the bottom. That's not how it would have been 200 years ago,” says Wasson.

To keep the young oysters from being smothered, the community volunteers, Reserve employees and MLML students and staff pushed long PVC pipes into the soft ground. To these, they attached mesh nets or clam shells, on which the tank-grown baby oysters had settled.

Rekindling relationships

Wasson has held several oyster restoration and one oyster tasting event in partnership with the local Amah Mutsun Tribal Band to help Native American communities reconnect with the mollusk species they stewarded sustainably for so long. “It makes the project even more meaningful to me,” says the ecologist. Additionally, Olympia oyster restoration team member Harris, who recently graduated, took on a position as ocean program manager with the Amah Mutsun Land Trust to support the Tribe in rekindling its relationships with oysters and other coastal species and habitats. The lessons learned from his experiments with Olympia oyster conservation aquaculture and outplanting will be published in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series.

So far, about half of the outplanted aquacultured baby oysters have grown to adulthood — an impressive survival rate. The researchers plan to keep going until they’ve added a million new oysters to the slough. At that point, the population should be big enough to sustain itself again and maybe even firm up the muddy ground with new reefs, Wasson hopes.

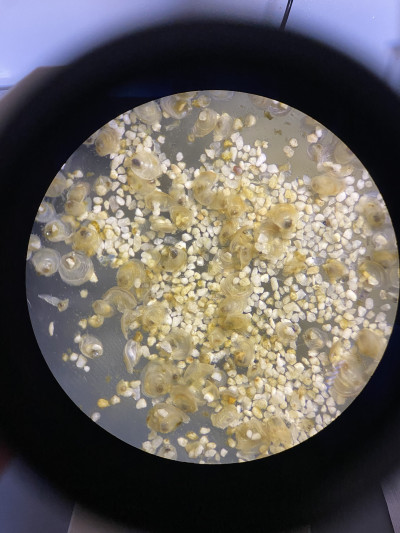

Naturally born baby oysters for the first time since 2012

Last fall’s discovery that thousands of baby oysters were growing in places where none had been outplanted makes her optimistic. It indicates that the Olys might have reproduced naturally in the slough “for the first time since 2012,” says Wasson. “So maybe the oysters we’ve put out there so far are already enough.” MLML’s Gardner will run genetic tests to ensure that new juveniles have enough diversity to avoid bottlenecks.

The conservationists hope to persuade commercial oyster growers to include Olympic oysters at their farms. Although smaller than Pacific Oysters, Olys are said to be particularly flavorful. And because they take at least two years to reach market size but start spawning after one, farmed Olys could reproduce before being harvested, boosting wild populations. “It could be a win-win,” says Wasson. “We could have our Olympia oysters and eat them, too.”

Learn more about Olympia oysters.