If you visit the Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve (TRNERR) 15 miles south of San Diego, you might get lucky and spot a rare Coastal California gnatcatcher in flight or glimpse the long ears of a black-tailed jackrabbit. One of the largest and last remaining coastal wetlands in southern California, the preserve supports an impressive biodiversity, including several endangered species.

But you might also notice trash of every imaginable variety poking out between the plants and in the mudflats. “We see the typical debris like plastic bags, bottles, and food wrappers. But also tires, building materials, refrigerators and mattresses,” says Kristen Goodrich, Director of TRNERR’s Coastal Training Program. Particularly after Southern California has been pounded by one of its periodic rainstorms, a “tsunami of trash,” as some call it, washes down the Tijuana River. Some of the debris floats all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Other ends up burying parts of the wetland including nesting habitat at the reserve.

The trash stems from construction sites, clandestine dumps and discarded litter. It collects throughout the canyons and along the roads and residences surrounding the Tijuana River, which separates California and Mexico, only to find its way into the estuary during storms. “Both countries are contributing to the problem,” says Theresa Talley, an extension specialist with California Sea Grant.

Consequently, any meaningful solution will need to be jointly developed, too. Talley and Goodrich were recently granted $299,996 in federal funding to support a cross-border community action coalition that also plans to reach out to the Kumeyaay Nation, whose ancestral tribal lands straddle the border. The project, “Cultivating a trinational Marine Debris Leadership Coalition to find solutions to complex cross-border land-based marine debris” will run for three years.

Cross-Border Collaboration: The Marine Debris Leadership Academy

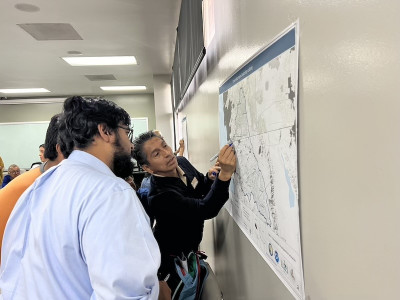

The initiative will build on a pioneering Marine Debris Leadership Academy (MDLA) that Goodrich and colleagues at TRNERR organized in 2023. Over eight weeks, more than 40 representatives from universities and colleges, NGOs and regional, federal, state and local agencies in the U.S. and Mexico met once a week for leadership training, technical presentations and field trips. They toured sedimentation basins and trash booms that were built to catch the trash that is carried during rain events. They visited upstream communities where urban sprawl has outpaced municipal waste pickup and litter accumulates like snow drifts in steep canyon landscapes. They looked at culverts, which “often become places where trash ends up because there is minimal, inconsistent or no collection services,” says Goodrich.

The issue is not just environmental but also humanitarian, she says. The trash can create hazards in the canyons themselves, for example. Goodrich once heard about a discarded mattress that blocked a culvert, causing head-high flooding in the vicinity. Later, this information was used to prepare collaborative flood modeling.

With the new funding, which comes out of a $27 million grant package to tackle marine debris as part of the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Goodrich and Talley want to foster and expand on the cross-border relationships that started blooming during the Leadership Academy. Although many of its participants had never met before, a group has stayed in touch after the program ended, organizing hikes and trash clean-ups and developing their own projects and campaigns through a communal WhatsApp chat.

Longer dry seasons, stronger storms

There’s a growing sense of urgency. “Climate change means that we have longer dry seasons, meaning longer time periods for trash to build up,” says Talley. “Then, when a storm hits it’s often bigger, with more torrential rain to flush even more debris downstream.”

Over the last ten years, community and volunteer groups have swarmed out repeatedly, trying to round up what trash they could during organized events. But “clean-ups serve more as Band-Aids than long-term solutions”, says Talley. “What is needed are solutions that prevent trash and debris from ending up in the environment in the first place.” Ideas include upcycling trash and coordinating with agencies in Mexico (where the larger part of the Tijuana River Watershed is located) to clear out culverts before storms are forecast to hit. “It's a complex issue,” says Goodrich. Both the U.S. and Mexico operate under their own sets of government regulations and can have different perspectives, priorities and concerns.

With the new grant offering funding for three years, the project team plans to kick off the coalition-building with a visioning summit in early 2025 to gather input from MDLA alumni and community leaders, to coincide with California’s rainy season, when the tsunami of trash tends to arrive. Goodrich in particular is hopeful. “The relationships that evolved from the first Marine Debris Leadership Academy speak forcefully to the power of connection and transcending boundaries, whether they are physical, disciplinary, or relational.”

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.