In 2018, the United States Lifesaving Association reported 29,125 rescues related to rip currents in California alone, and 68 deaths nationwide. Over the past decade, researchers estimate that nearly 85% of rescues on US West Coast beaches were due to rip currents.

While rip currents are one of the main beach hazards in California, with a little preparation you can easily avoid them. A 2017 study showed that while most beachgoers are aware that rip currents exist, many people cannot identify what they look like.

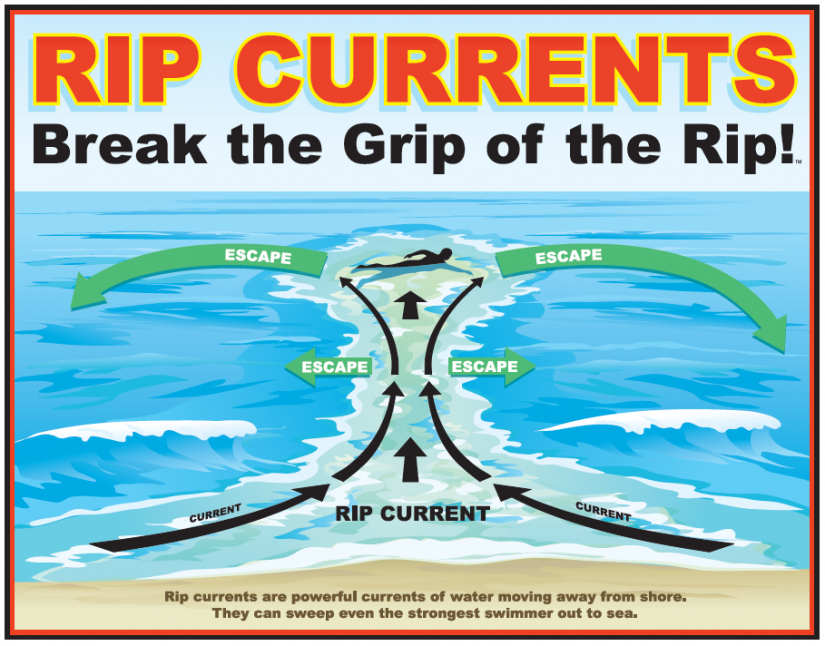

To spot a rip current, look for a break or flat spot in the waves, or as an area of white water that moves away from the shore. Rip currents are strong currents of water that flow from near the shoreline, outwards to sea. Surfers use them to help paddle out past breaking waves.

To avoid getting caught in a rip, check National Weather service surf zone forecasts before heading to the beach, and talk with a lifeguard before getting in the water to find out about current conditions. Always swim in view of a lifeguard. And if you do end up in a rip current, staying calm and knowing what to do can ensure you make it safely back to shore.

Read on to learn more about rip current myths, and find links to more resources on our website.

Myth: Rip currents pull you under water.

In fact, rip currents carry people away from the shore. Rip currents are surface currents, not undertows.

An undertow is a short-lived, sub-surface surge of water associated with wave action. It can drag you down, but it’s not truly treacherous because you won’t be held under for long. Just relax and hold your breath, and you’ll pop to the surface, often on the back side of the waves breaking near shore.

Rip currents are surface currents that can move as fast as five miles per hour, faster than even Olympic-level swimmers. But while rip currents can move fast, they won’t take you far off shore. If you find yourself floating away from shore, try to relax, float, and wave for help.

Myth: If you get caught in a powerful rip, you can be swept out to sea forever.

Even under the worst conditions, you won’t be swept to the middle of the ocean, though it could be a long swim back to shore.

Most rip currents are part of a closed circuit, says Robert Anthony Dalrymple, a coastal engineer and rip current scientist at Johns Hopkins University. If you ride a rip current long enough – float along with it – you will usually be taken back to shore by a diffuse, weaker return flow.

The exception to this occurs during fierce storms, when pounding surf sets up powerful longshore currents that shed turbulent eddies. The seaward-flowing arms of these swirling currents may look and feel like “rips,” but they are not part of a circulation cell that will slowly carry you toward shore. Instead you’ll be deposited outside of the surf-zone, sometimes a distance of multiple widths of it. When the surf is big, most people should stay out of the water.

Myth: If you don’t see a rip current, you don’t have to worry about one.

In some cases, rip currents can form spontaneously, in response to the interaction of a lot of waves coming together from many directions at once.

These wave-induced “flash” rips may last only a few minutes or they may pulse – wax and wane – over a longer period of time, says Bob Guza, a coastal oceanography professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego, who has studied transient rip current formation in North Carolina and had California Sea Grant support to study surf-zone dynamics, including rip currents. Flash rip currents are not as powerful or dangerous as other rips but they can nonetheless take people off guard and induce panic.

Written by Christina S. Johnson (2013). Updated May 2020.

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.