Over two days during the 2024 beach season, six swimmers drowned in rip currents in the U.S., including the parents of six children. Annually, an estimated 100 U.S. residents lose their lives to rip currents — narrow channels of fast-moving water that can form near beaches. With $150,000 in funding from the U.S. Coastal Research Program and the National Sea Grant Office, a team of researchers from California Sea Grant, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the University of California, Santa Cruz, and California Polytechnic State University-San Luis Obispo has developed a new tool to address this hazard: a first-of-its-kind mobile app that helps beachgoers detect rip currents in real-time, even at remote coastal locations unprotected by lifeguards. Called RipFinder, the app recently entered beta testing.

On average, U.S. lifeguards rescue a swimmer from a rip current every five minutes during daylight hours. “Rip currents are by far the greatest public safety risk at the beach,” says Greg Dusek, senior scientist with the NOAA National Ocean Service. Despite warning signs and NOAA’s six-day rip current forecast, many beachgoers are unfamiliar with the deadly phenomenon and do not know how to avoid it.

Faster than an Olympic Swimmer

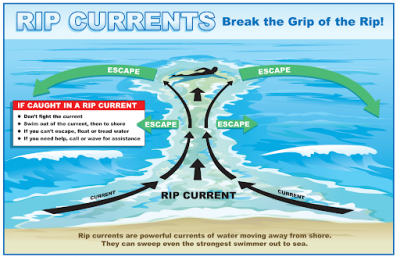

Rip currents pull swimmers into the open ocean at speeds of up to eight feet per second — making them faster than Michael Phelps during his world record performance at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. But these currents can take different forms, depending on the beach and local conditions. Some appear at predictable spots near jetties and gaps in sandbars while others emerge randomly, without warning. Rip currents occur along all U.S. coasts, including the shores of the Great Lakes. “Anywhere you have waves, you're going to have rip currents,” says Dusek.

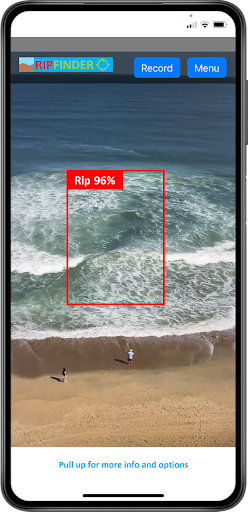

With RipFinder, beachgoers can check for rips using their phone’s camera. Fahim Hasan Khan, an assistant professor of computer science and software engineering at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, used machine learning to teach the app to recognize rip currents' characteristic signs, such as muddy-looking patches of water or darker water where waves are breaking less frequently. RipFinder shares the location of the rips it detects with NOAA, which will use this data to improve its rip forecasts.

Currently, lifeguards and surfers on the West and East Coast are testing the app. “Any rips the tool misses we’ll add to our training data so that the updated version will recognize more and more of these currents,” says Alex Pang, a professor of computer science and engineering at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Like lifeguards, many surfers are familiar with rips, in their case because they often use these currents to bypass the surf and to quickly get to the surf break with less effort. RipFinder will be released to the general public early next year.

Teaching Safety Through Technology

Swimmers caught in a rip current are advised to move parallel to the shoreline to escape its powerful pull. Such advice is easy to forget in the panic of the moment, as NOAA’s Dusek knows firsthand. The rip current researcher vividly remembers the time a lifeguard took him into the water so that he could experience the object of his studies firsthand. “Getting pulled from the shore is just one thing. There is also the feeling of chaos with waves breaking all around and sea spray hitting you in the face. It's hard to see where the coast is,” he recalls. “Even though I’m a pretty strong swimmer and had a lifeguard with me, it was disconcerting.”

RipFinder might be most useful to beachgoers on remote shorelines without lifeguards. But the tool’s developers warn against depending solely on the app. “It’s never going to be 100% accurate,” says Ashleigh Palinkas, a marine research associate with California Sea Grant. “All it takes is something on the camera lens.”

Ideally, though, RipFinder’s users might get to a point at which they won’t even need the tool anymore. The developers hope beachgoers will consult the app to learn how to recognize the visual signs of rips — so that one day they might be able to identify these currents without digital help.