After a long period of decline, nuclear power is having a moment. Here in California, Pacific Gas & Electric is seeking to extend its license to keep Diablo Canyon, the state's last nuclear plant, operating. The rationale is climate change: nuclear reactors offer a reliable supply of energy, and they do not directly emit any greenhouse gasses.

But Jennifer Marlow, an environmental law professor at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, points out that climate change will also exacerbate one of the unanswered questions about nuclear facilities. This is particularly true at Humboldt Bay. Here, on the edge of a bluff, little more than a hundred feet from the water, six casks are set below the ground, embedded within a concrete vault. These casks are filled with nuclear waste — “spent nuclear fuel,” as it’s known in the industry — that’s leftover from a now-decommissioned nuclear plant.

The water in Humboldt Bay is projected to rise three feet over the next four decades, Marlow notes. That’s enough so that during King Tides, low-lying areas around the spent nuclear fuel site will flood, leaving the site completely surrounded by water.

The officials who oversee the facility do not seem worried. Some locals, though, are concerned — and not just about climate change. The shoreline at the base of the bluff has eroded more than a thousand feet since 1870. Tectonic activity in the region is extraordinarily high. Humboldt Bay, meanwhile, is a precious and beloved ecosystem, and the sacred ancestral homeland of the Wiyot people. In addition to a national wildlife refuge and the largest contiguous old-growth coastal redwood forest in the world, the Bay supports economically valuable marine fisheries and oyster aquaculture, with offshore wind soon to be added to the list of assets.

Spent nuclear fuel is, for good reason, highly secured — but this means it’s engineers and scientists who make most decisions. And whether it will be safe for decades at Humboldt Bay in light of increased coastal hazards is an open question.

“I think people feel like there’s no solution,” Nate Faith, a former environmental science instructor who lives near the site, said during a series of workshops that Marlow convened last year. “We feel like we’ve been abandoned by government.”

Marlow’s goal with the “44 Feet” project — which was developed with funding from California Sea Grant and the Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology — was to elevate voices like Faith’s. The workshops brought together a varied group of locals who considered the diverse views on the site and the different kinds of futures it might face.

A brief burst of power

Almost all of the nuclear plants in the United States were built between 1970 and 1990. Since then, though, the industry has stagnated. This spring, when a new nuclear plant began supplying power in Georgia, it was just the second reactor to come online in the U.S. since 1996.

The big challenge for the nuclear industry is the massive expense of building reactors, costs that are driven in part by safety regulations. Fans of nuclear power suggest we need to find a way to up investment and streamline regulations. After all, the nation’s nuclear plants provide more power than our wind and solar farms combined. Even better, while the wind sometimes slows and clouds can block the sun, nuclear runs consistently, offering a way to fill the gaps.

On paper, then, nuclear has a lot going for it. Even factoring in the rare but famous disasters like Chornobyl and Fukushima, nuclear power has been far less deadly than coal or natural gas when measured per unit of energy produced. Indeed, wind farms are slightly more deadly than nuclear plants, according to some calculations.

But nuclear plants aren’t built on paper. They are built in places like Buhne Point.

A plant on a hill

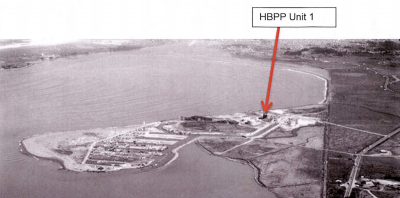

Buhne Point is an old upland bluff that sits just across from the mouth of Humboldt Bay. The plant built here, the seventh to come online in the U.S., began operating in 1963. At first, no one understood the implications of three tectonic plates meeting just off the local coastline. Now, though, the region is known for the highest concentration of earthquake events anywhere in the United States.

That geology became a problem after the Humboldt nuclear plant was temporarily shuttered for refueling in 1976. The plant’s owners, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) discovered what it called “new seismic information” while the plant was sitting idle. Before they could restart the reactor, they’d need to complete a retrofit.

Then, in the wake of a headlines-grabbing nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island, in Pennsylvania — which prompted new national safety regulations — PG&E determined that the increased expenses required to reopen were too high. The company decided to close this plant. But you can’t simply lock the doors of a nuclear plant and walk away. Even after it’s been “spent,” nuclear fuel remains radioactive for thousands of years.

When national regulators approved PG&E’s plan to decommission the Humboldt plant in 1988, current laws charged the federal government with taking possession of all spent fuels across the nation within ten years. The idea at the time was to put this waste underground at a remote site in Nevada.

As it turned out, though, Nevadans were not eager to have a nuclear dumping ground in their backyard; the local geology was also less accommodating than scientists first believed. We’re now nearing 40 years since the Yucca Mountain site was first proposed as a nuclear repository. Funding for the project was halted in 2010 and despite $12 billion in expenditures, all that exists is a five-mile-long tunnel. It’s unclear whether the project will ever be finished.

In the meantime, most spent fuel has been stored on the site of retired plants, in storage systems that are meant to be temporary. This is the case at Humboldt Bay.

In 2005, federal regulators granted PG&E a license to conduct on-site storage for twenty years at the Humboldt Bay Independent Spent Fuel Storage Installation (ISFSI). In 2020, with no progress on a national storage facility, the license was extended through 2065, though PG&E’s current plans assume that the federal government will pick up the waste in the early 2030s. As the company itself notes, this date is entirely speculative.

Jana Ganion, the sustainability and government affairs director of Blue Lake Rancheria, a local tribe, and one of the participants in the 44 Feet Project, suggests that the waste should be treated as if it would be there forever. “That’s the paradigm we should plan for,” she said at one of the workshops.

And the presumption that the fuel will be gone within ten years is only one of several places where locals are worried that the paperwork does not match the reality.

A precarious place

The “44 Feet Project” is named for the distance that the spent fuel at the top of the Buhne Point, sits above mean sea level. The site is located along one of the most dynamic and erosive sections of Humboldt Bay, home to the highest rates of relative sea-level rise on the west coast.

Marlow, along with Cal Poly Humboldt master’s student Alec Brown, has looked through hundreds of pages of paperwork in their efforts to understand the site. They found that in a 2005 report, a PG&E geoscientist suggested that local uplift would offset the rise in sea levels, at least barring a major earthquake. But in a 2017 analysis, academic geologists noted that the land along Humboldt Bay is subsiding. A tide gauge near Buhne Point showed particularly high rates of vertical displacement.

As for the local tectonic activity, a 2021 PG&E report described the “maximum credible” event as having a magnitude of 8.8. That figure is based on a study from 1993. Since then, scientists have begun to investigate the possibility of even larger quakes in the region. State paperwork, meanwhile, shows that officials believe the site has been designed to withstand a magnitude 9.1 quake. (Due to the logarithmic nature of the scale, would release nearly three times as much energy as a magnitude 8.8 event.) Understandably, many locals want these discrepancies to be analyzed.

Marlow believes a more holistic examination of the factors at play is necessary: the local geological context; the political situation, at federal, state, local, and tribal levels; the safety risk factors from increased coastal hazards; and the cultural, ecological, and racial make-up of the region. Perhaps most importantly, she wants to ensure a wide group of locals get to weigh in, rather than just a few scientists selected by PG&E.

Collaborative thinking

The “44 Feet” project began its local engagement with 24 interviews, each roughly an hour long, with various people who had a professional or personal interest in the site. Marlow and Brown wanted to map out areas of agreement and disagreement before beginning to bring a group together.

The researchers asked each interviewee to nominate potential participants in the subsequent workshop. The resulting group, which consisted of 29 participants in total, included representatives from local tribes, state and local governmental agencies, elected officials, members of Congress, non-profit organizations, advocacy groups, academics, and PG&E itself. The group first gathered in June for a curated walk to the ISFSI site.

The walk began at a beach just south, where an elder from the Wiyot Tribe explained the importance of this place to her people. Then everyone climbed to the top of a wall of rocks where a local sea level rise expert and a local geologist explained the risks that stem from climate-driven sea-level rise and tectonic shocks. They highlighted the history of erosion here: the jetties that federal engineers built at the bay’s narrow opening in the 1890s directed waves toward Buhne Point, washing away nearly 1,500 feet of soils. The wall the group stood atop was built in the 1950s, to prevent any further land loss.

As they finished the walk atop Buhne Point, outside the fence that secures the ISFSI, the group discussed the effects of increased King Tides, or high water levels that occur doing a new or full moon, and how climate change is already altering the ecosystem here, a reminder that at this site “the only reliable constant is change,” as Brown and Marlow wrote in a summary report.

The next day, participants reconvened for the first of two workshops focusing on a simple central question: whether the spent nuclear refuel on Humboldt Bay should be relocated before the end of the ISFSI license in 2065 — and before three feet of sea level rise islands the site.

To deal with the range of uncertainties, the group used a “scenario-planning method” — an approach that PG&E has used itself, as Marlow notes. This meant developing a map of potential futures that fork apart at several decision points. In August, the workshop participants reconvened to develop recommendations.

Unsurprisingly, the group did not come to consensus on whether the spent fuel needed to be relocated or whether it could be protected on site, and if so, for how long. Everyone agreed, though, that the complications at Buhne Point are only going to grow as time goes on. And everyone was clear that more information is needed, especially about sea level rise and future climate impacts.

“In order to design a project to protect the hill, you have to figure out what you’re protecting from, and how much,” Kate Huckelbridge, the current executive director of the California Coastal Commission, noted at one of the workshops.

Marlow believes there should be an independent, third-party review of the science, rather than the current process, in which PG&E hires experts to review the risks. Humboldt Bay, she notes, is not the only site in California facing potential risks from spent fuel. Earlier this month, two California representatives, Mike Levin, D-49th District, and Darrell Issa, R-48th District, reintroduced legislation in Congress meant to prioritize the removal of spent fuel from sites with high population centers and high seismic risk. Humboldt may be too small to qualify, but Marlow and Brown hope that 44 Feet can support amendments that weigh risk factors such as coastal hazard risk more heavily and that locals can join with other communities, like San Onofre and Diablo Canyon, to advocate together for increased oversight at the state and local levels

Marlow emphasizes that she is not anti-nuclear. “We’re just trying to understand multiple futures,” she says. “We want more information to support a better and more informed choices.”

The 44 Feet Project is seeking a graduate research assistant to join the project this fall. Details can be found here.