It’s 8:30am on a Tuesday morning at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory. Researchers Kristin Aquilino, Emily Hubbard and Kat Magaña have been here since 6:00, preparing for a long day of abalone spawning.

After the abalone are placed in buckets with a “love potion” of very dilute hydrogen peroxide, it can take hours until they release eggs or sperm—if they spawn at all.

Since white abalone are highly endangered, their reproductive strategy of spewing their sperm and eggs into the water is unlikely to lead to new young in the wild—too few are now left in the wild to successfully mate. This laboratory spawning is part of a statewide effort to rebuild the population. Even in the lab, spawning is difficult to predict. In the last attempt in February, only four of 21 animals spawned. They’re expecting a long wait.

But just a few minutes after 9am, Magaña spots a cloud of grey-green dust—like poorly filtered green tea—emerging from one of the females. The team rushes into action, carefully emptying the bucket and covering the snail with fresh seawater.

A few minutes later, a male spews out a white cloud of sperm. Soon after that, it’s a chaos of buckets as the abalone begin to spawn one after another. As more volunteers arrive, buckets are shuttled into a cold room and the team begins mixing up sperm and eggs from different individuals, making quick calculations to get the ratios right and maximize genetic diversity.

By the end of the day, seven female abalone had spawned over 25 million eggs, four males had produced sperm, and the team had mixed and matched to create eight mixes of embryos—a huge boost for the genetic diversity for the captive abalone population at BML.

Restoring an endangered species in a changing environment.

Aquilino’s white abalone facility is not only a fertility clinic and nursery for abalone, but also one of the leading abalone research labs on the West Coast. Spawning abalone is the first step in restoring the wild population, which was decimated by overfishing in the 1970’s to 1990’s. But for any hope of success, researchers will need to better understand how the animals will cope with changing ocean conditions related to climate change.

Aquilino says, “We have to contend with the fact that we are putting them into an ocean with conditions that their parents and grandparents might have never experienced.”

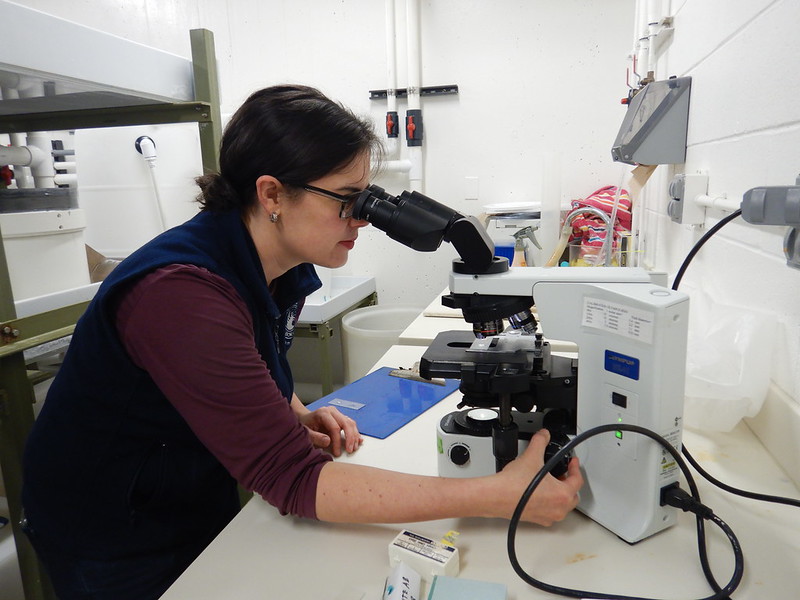

In one project funded by California Sea Grant, Aquilino is working with California Department of Fish and Wildlife biologist Jim Moore to understand a bacterium that infects both wild red and white abalone as well as farm-grown red abalone in California. Previous research has shown that persistent warm water temperatures (above 18 degrees C/64 degrees F), cause infected abalone to show symptoms of the disease, while in colder water the animals can continue to thrive.

The disease, known as withering syndrome, is difficult to manage because by the time abalone show symptoms—a lack of appetite and retraction, or withering, of the body—they are already too sick to survive.

To better understand the relationship between illness and water temperature, Aquilino and Moore have set up an experimental culture system where they can manipulate water temperature and study the sublethal effects of the disease, including on reproduction.

In another project funded by the California Ocean Protection Council, Aquilino, Moore, UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory researcher Eric Sanford, and Dan Swezey, lead scientist with the Cultured Abalone Farm, a commercial aquaculture facility based in Santa Barbara CA, are exploring how the impacts of climate change in the ocean—ocean acidification and warming water— will impact captive breeding efforts, stocking, and eventual recovery of the species.

“To recover white abalone, we need to figure out what makes them tick both in the lab and in the wild. Understanding how factors like disease, temperature, and ocean acidification affect abalone health and reproduction will allow us to produce more captive-bred animals for stocking and optimize their ability to reproduce on their own in the wild,” says Aquilino.

Bringing back wild abalone?

The ultimate goal of the white abalone research program is to restore the wild population. At the same time, research conducted at the laboratory could prove useful to aquaculture growers raising the related red abalone and struggling with the same challenges of disease and unpredictable spawning efforts.

“Ultimately, we’re studying how changing ocean conditions will affect all species of abalone, both the wild populations we’re trying to conserve and farm-raised populations that we raise for food in California” says Swezey. “Abalone are still a very popular seafood in the state and on the minds of many Californians.”

With the successful spawning attempt this spring, Aquilino’s current focus is on finding enough space to house the young abalone until they grow large enough to be released into the wild—one to three years. Some of the young abalone have already been transferred to facilities at Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, Aquarium of the Pacific, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

A collaborative consortium of white abalone researchers, including NOAA and California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), are planning to release the first batch of white abalone into the wild soon, which will be the first such attempt with endangered white abalone.

“CDFW and NOAA have been working hard to test the best strategies for outplanting, in terms of time of year, location, and animal size,” says Aquilino. “We are learning so much about these animals, but there is still so much more to discover.”

Read more:

UC Davis: Endangered white abalone program yields biggest spawning success yet

California Sea Grant: Study of mollusk epidemic could help save endangered sea snail

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.