Damaged Gear

It was a Saturday morning in the early spring. Cars pulled up to the California Sea Grant Extension satellite office and dozens of people walked inside to sit down and talk. The meeting inside, the likes of which had never occurred in California before, took eight hours.

“That was April 9, 1983 — I will never forget that,” said John Richards, a former Area Marine Advisor for California Sea Grant who was present at this meeting.

This year, it has been forty years since that eight-hour union, but Richards still remembers this day clearly. The Mediation Institute had organized a meeting between a handful of representatives from the California coast’s commercial fishing industry and the rapidly expanding offshore oil industry to discuss ocean space use conflicts.

Over the course of eight hours, voices would be raised and emotions would flare, but the most groundbreaking thing of all was that both sides had agreed to be in the room together.

This meeting would turn out to be a threshold moment for both industries, and a jumping off point for improved integration of space use in California’s waters for decades to come.

The initial complaint was first brought to Richards’ attention seven years earlier, in 1976. Wellheads put in place by the oil industry were jutting from the ocean floor enough to tear the nets of trawlers that fished the area. Not only did the damage cost fishermen in gear replacement, it also was keeping them off the water while repairs were made, impacting their livelihoods.

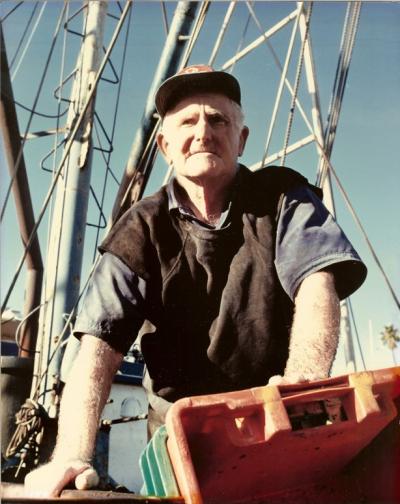

Richards had just taken a job at California Sea Grant as an area marine advisor. Years earlier, as an undergraduate studying marine science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he had worked for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (formerly, Fish and Game). In that role, he surveyed and monitored the trawl catch, spending early mornings cataloging the daily catch and talking to fishermen. This is how he met Ralph Hazard, a lifelong fisherman from Santa Barbara who was experienced in fishing traps for lobsters and crabs, trawling and more. The trust established between the two during trawl catch surveys years earlier would soon play a key role in Richards’ new position, when Hazard went to Richards and brought the wellheads issue to his attention.

Fishermen had already tried approaching members of the oil industry to voice their concerns, but their efforts had been largely dismissed.

One such fisherman was Gordon Cota. In the early 1970s, Cota was a young man who had just returned to California after finishing a political science degree from the University of Hawaii. He got to work on a couple of fishing boats, learning the ropes from more experienced fishermen, including Hazard. Eventually, Cota set up his own operation, a 19-foot skiff he christened “Topo.” Cota used Topo to navigate California’s inshore waters, fishing for lobsters and crabs. He remembers setting traps in the Elwood Beach area but losing them to what he assumed were oil vessels. His first attempt at broaching the subject with a member of the oil industry did not go well. He had approached a man operating an oil service crew boat and asked him to be careful around the traps. Cota remembers a few sharp words being exchanged before the crew boat backed up and left. But, his political science degree would come in handy. He began by talking to people in both industries about the issues he was experiencing.

“The oil company people, when I talked to them, I said, ‘Look, I want to catch fish — that's how I'm making a living. You want to get oil — that's what you want to do,’” Cota said. “So let's figure out how we can coexist here.”

In his new role at California Sea Grant, Richards too began looking into the issue and found that the oil industry had been using Lambert grid maps (conical projections) to chart their operations. This meant that wellheads and other oil company structures weren’t showing up on the navigational maps that the fishermen relied upon. When Richards layered the Lambert grids over the navigational maps showing where the fishermen were having issues, the problem became clear.

“Three trawlers had told me that they lost their gear on this one spot,” Richards said. “Sure enough, there were a couple out there that were definitely wellheads.”

With help from the office of the U.S. Geological Survey in Ventura, Richards then designed a system for helping fishermen avoid wellheads and identifying lost/damaged gear incidents when they did happen.

As a California Sea Grant area marine advisor, Richards knew the importance of remaining a neutral party.

“You're not taking sides with anybody,” Richards said. “You're trying to provide the best information and help solve these problems — but you're not taking sides.”

Being able to identify problem spots on both maps was a good first step, but the trouble wouldn’t end there. Conflicts between the oil and fishing industries accelerated as offshore oil leasing rapidly increased in the early 1980s. There were more survey vessels in the waters and oil companies were submitting dozens of new Plans of Exploration to the California Coastal Commission every month. Before long, conflicts between industries reached crisis proportions. It wasn’t just issues with gear — geophysical (seismic) surveys and support boat traffic were causing additional problems. The fishermen were beginning to float the idea of litigation.

Richards had a different idea.

Finding Common Ground

In the early 1980s, Doug Uchikura was part of the Chevron team based in Santa Barbara. A lawyer by trade, Uchikura’s job at the time was to help get permits for the onshore oil and gas processing facilities and the pipelines connecting offshore projects to those onshore facilities. It was around this time that he first became aware of the conflict with the fishing community.

“They were very adept at representing themselves,” Uchikura said. “They really did function as a pretty tight community in their business and they weren't shy about coming forward and letting us know some of their concerns.”

Captain Hazard, the same trawler who brought the issues to the attention of Richards, invited Uchikura out on his boat to see if they encountered any wellheads or pipeline obstructions. Uchikura accepted his invitation and saw it as an indicator that a joint approach to problem-solving between the two groups just might work.

“We weren't trying to take away their livelihoods,” Uchikura said. “And we didn't want them interfering with our livelihood, either — the production of energy. So we just felt like it made sense to work with them.”

Meanwhile, Alana Knaster happened to stop by Richards’ office to talk about an issue involving sea otters. Knaster was a professionally trained mediator from the Mediation Institute. Her job was to help conflicting parties navigate discussions and reach agreements that were mutually beneficial, and she was trained to focus on common ground, while navigating highly stressful situations and emotional topics. The serendipity was too much for Richards to ignore.

“I was thinking that we need somebody like a mediator, and then all of the sudden this mediator comes into my office,” Richards said.

Richards knew that a brewing legal battle between the fishing and oil industries would be both expensive and unproductive. But if both parties would consent to talk about the issue, perhaps they could find a path toward resolving the conflict. It was important as a California Sea Grant representative for Richards to remain impartial, and that’s also what made him the right person to get the ball rolling. But to succeed, he would need Knaster to take over.

Knaster jumped right in, rounding up representatives from the oil industry who were engaged in the topic and committed to finding solutions. Richards did the same on the fishery side. Together they were able to set a date for their first formal meeting—April 9, 1983.

“How do people get to trust you? You have to demonstrate that you're trying to solve a problem,” Knaster said.

There were representatives present from three different fishing ports as well as multiple oil companies including ARCO, Texaco and Chevron. Other attendees included representatives from the state and federal agencies in charge of regulating both industries. The first meeting was contentious, but it worked. By the end of the day, both sides had agreed to next steps.

“Our first meeting was a very big test of just, can we sit in a room together and not kill one another,” Knaster said.

What was apparent to both sides from the outset was that in order to reach a mutually beneficial solution, it was going to be essential to have a neutral, third-party guide through the process. “It was all about creating a process,” Knaster said. “A legitimate, fair process that facilitated communication. You had two interest groups who wanted to work together, and if that process worked, they didn’t need to go the legal route.”

It was out of these initial meetings that the Joint Oil/Fisheries Liaison Office was created.

JOFLO is Born

When John Richards wrote the job description for the oil/fisheries liaison, he may as well have had Craig Fusaro in mind.

Fusaro had a Ph.D. in Biology and was then doing marine science consulting for Ecomar, an applied ecology/oceanography consulting firm in Goleta. Ecomar harvested mussels for commercial sale from the substructures of offshore oil production rigs. Fusaro had also helped design and perform a number of applied oceanographic studies related to offshore oil exploration and production in the Gulf of Mexico, Alaska and off Baltimore Canyon, spending some time on the oil rigs during this process.

Fusaro was familiar with both the oil and fishing industries but exclusively allied to neither. That position of neutrality was key, but also not easy.

“It was not simple, and repetition was important in driving the role home,” Fusaro said.

The oil industry put up the funding for the liaison office, with the knowledge that the fishermen would be involved in oversight. After Fusaro was hired in October 1983, JOFLO was staffed and running. Over the next 35 years, Fusaro and the JOFLO would help the oil and fishing industries address many critical conflicts.

“Gaining trust in these relatively ‘closed’ communities wasn't instantaneous or simple,” Fusaro said. “Time was required, along with holding to neutrality principles.”

One of the next big issues to address was the debate over whether acoustic impacts from seismic testing were negatively affecting the fishery. Fishermen argued that they were seeing fish populations disperse due to seismic acoustic signals and oil company representatives pointed out that correlation does not equal causation. This issue led to the formation of a Seismic Subcommittee, and then a Science Panel, composed of researchers approved by both industries, to investigate whether a research effort was warranted. The panel convened and determined that it was possible that the seismic signals were impacting fish dispersal, so a research effort was needed.

Over the course of several years, studies revealed that: seismic survey airguns did indeed reduce the catch per unit effort of hook and line fishermen around Point Conception and Morro Bay; sardine larvae and juveniles were affected, though not enough to be statistically significant at the population level; and seismic survey airguns affected the ability of Dungeness Crab larvae to transition from one larval stage to another. A fisheries economics study illustrated that these effects on the fishery were economically impacting fishermen, which led to the Local Marine Fisheries Impact Program (LMFIP), a successful impact mitigation program that funded collaborative fisheries research and other types of fisheries enhancement projects.

Another big achievement of JOFLO during this time was the establishment of traffic corridors so that both industries would know where the other would be. The oil companies agreed that their vessels would use these transit lanes, and fishermen agreed to stay out of those corridors. The lanes were set out to the 30-fathom contour — about 2-3 miles offshore. Still in use today, the current map runs from Morro Bay down to Port Hueneme and has been established since 1995, giving both industries over a quarter century of use. These now-established corridors have nearly eliminated traffic-related fishing gear loss.

One noteworthy attribute of the traffic corridors, and nearly every agreement made in JOFLO, is that none of them are legally binding. To work, they require buy-in from both sides.

“JOFLO has no legal agreements,” said Mary Nishimoto, current JOFLO Liaison who took over after Fusaro’s retirement in 2017. “It's all cooperative agreements.”

Another important focus was finding ways to increase access to relevant information. In 1983, Richards received a $22,000 grant from the federal Coastal Energy Impact Program to create a monthly newsletter to help disseminate relevant information to interested recipients — particularly about upcoming and ongoing oil and fishing activities in the area. “The Oil and Gas Project Newsletter for Fishermen and Offshore Operators” was funded by the oil and fisheries industries, county agencies and the Sea Grant Extension Program once the grant funding ran out. The newsletter became an invaluable resource, says Richards, thanks to the hard work of his collaborators — Carolynn Culver, Laura Manning, Debbie Haberland, Karen Worcester and Fusaro. Today, the newsletter hardcopies are bound into nine volumes and stored at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

JOFLO also inspired new collaborative efforts. When international seafloor fiber optics cable companies came to the Santa Barbara Channel, they approached the JOFLO to become part of that ongoing process. While this didn’t happen, a “Central California Joint Cable/Fisheries Committee” and “Southern California Cable/Fisheries Committee” were also created, using the JOFLO model of joint factfinding, communication and cooperation offshore.

JOFLO is no longer an experiment, but is now considered a 40-year institution.

If JOFLO hadn’t emerged from the center of this conflict, says Cota, he doesn’t think things would have worked out at all.

“One side or the other would have thrown a wrench in the whole process,” Cota said. “But it was because of mutual cooperation and maybe some respect.”

Ongoing Potential

The track record of JOFLO — forty years of successful ocean space use negotiations between the oil and fisheries industries — speaks for itself. And it created a valuable platform upon which other ocean space use issues could be navigated.

“All the things that happened historically in JOFLO to set up this structure, have helped to keep the peace offshore and help fishermen feel that that they can work offshore with the oil industry out there too, without hard feelings if there ever should be conflicts,” Nishimoto said.

Continuing that threshold of trust still depends on transparency, good listening skills and clear communication, says Nishimoto. In many ways, JOFLO is a blueprint for addressing current and future ocean-sharing issues. Which is significant, since marine spatial planning issues continue to emerge.

“Having a liaison between industries for offshore issues is really important,” Nishimoto said. “And especially now, it's something to really think about because of offshore wind and the Aquaculture Opportunity Areas that are going to be established.”

Aquaculture enterprises take up mostly nearshore areas within state waters, and frequently receive pushback from fishermen, recreational boaters, residents and more. Similarly, offshore wind is a growing industry, and the expansion of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in California is another space factor. As California continues to negotiate space — as well as other factors such as environmental impact and resource management — it’s clear that it is possible to share the ocean, as long as involved industries are invested in solutions.

“It seems like a big ocean, but there’s a lot of conflict that can arise, and a lot of concern and anxiety,” Nishimoto said. “I'm really hopeful that there is going to be fair collaboration and cooperation allowed to develop as offshore planning continues in these different arenas.”

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.