Droughts and sinking groundwater levels due to climate change and water consumption have become a familiar worry in many parts of the world. But coastal California is poised to soon encounter a very different kind of problem: Levels of groundwater may rise.

“It’s a concern,” said Ben Hagedorn, Associate Professor of Geological Sciences at California State University Long Beach.

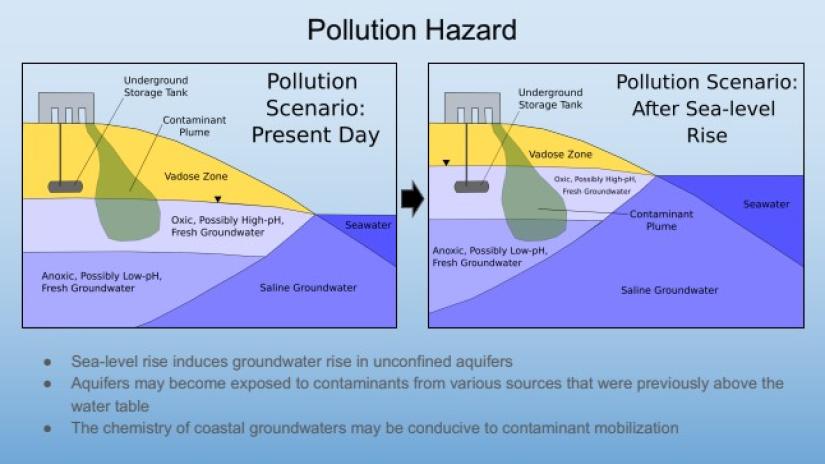

“What we see near the coast is that the rising sea level pushes up the saline groundwater,” he said.

In the process, the fresh groundwater used for drinking gets pressed toward the surface as well since it usually floats on top of the heavier salty groundwater. This could make coastal regions more prone to flooding, but there are also more insidious consequences.

As the rising fresh water seeps into surface soils, toxins such as cadmium and lead from hazardous waste sites, landfills and other contaminated areas could get flushed into drinking supplies, Hagedorn said.

With funding from California Sea Grant and the California State University Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology (COAST), Hagedorn and fellow scientists have started to map out areas in the state that are most likely to be affected.

Many municipalities along the California coast already struggle to provide safe and reliable access to drinking water for their growing populations. Often, the problem is made worse because water suppliers have to avoid the most shallow and easiest-to-reach aquifers because, even now, those aquifers tend to be contaminated by agricultural chemicals or industry and urban surface runoff.

Rising levels of fresh groundwater could make this problem more widespread and also wash toxins from shallow aquifers into the deeper reservoirs that currently provide drinking water. And soluble pollutants aren’t the only concern.

“When you have plumes of contaminants in aquifers, they can degas and generate toxic vapors,” Hagedorn said. These vapors can then push into buildings through cracks in the construction material or via utility lines and low-elevation windows.

In some areas, scientists are already noticing that levels of fresh groundwater are inching higher, and it’s going to get worse, Hagedorn said. Even parts of the state where the soil is free of man-made chemicals could see problems since many rocks in Southern California naturally contain high concentrations of toxic substances such as arsenic.

“Right now, they’re trapped in the ground,” he said. “But as the groundwater rises and inundates the rocks, they could become mobilized.”

Existing maps are not detailed enough to predict with confidence where fresh groundwater might become contaminated. Hagedorn and other scientists are building models by combining sea level rise data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) with information from the California Department of Public Health and the California Environmental Protection Agency about sites that have leaked contaminants in the past.

“Obviously, areas affected by sea level rise that have a lot of contaminants in the soil are high-risk,” Hagedorn said.

The $211,000 project was selected along with two others on sea-level rise through COAST’s State Science Information Needs Program. COAST provided $800,000 and California Sea Grant provided an additional $300,000 for a total of $1.1M in research funding.

As the team zeroed in on two pilot regions – the Oxnard area and around coastal San Diego – one thing became apparent. Sea level rise-induced drinking water contamination will disproportionately affect economically disadvantaged populations.

“For various reasons, many of these populations in Ventura County live close to the coast, in areas that have historically seen a lot of agricultural applications, such as pesticide and fertilizer-related contamination,” Hagedorn said.

Some coastal communities are already working at keeping the rising seawater out of the ground, particularly in South Bay areas like Hermosa Beach, Redondo Beach, Torrance, Long Beach, and Seal Beach. In these regions, municipalities have pumped so much fresh groundwater from the subsurface that this in itself has caused seawater to seep in.

In response, some water agencies have started to inject clean water into the ground, effectively creating a barrier against the encroaching salt water. While this does work, it’s unlikely to provide a solution against sea-level-driven groundwater rise on a broad scale.

Hagedorn suggested water authorities should instead take a new look at hazardous waste sites that are currently considered remediated.

“There are a lot of older locations, some dating back to the 1970s or even the 1950s when remediation technologies were not what they are now, that may still contain a lot of contaminants,” he said.

Additional remediation may be necessary to prevent these toxins from becoming mobilized as the water tables rise in the soil.

In the coming months, Hagedorn plans to develop risk indexes for all coastal watersheds in California – ideally supplemented by real-life wells in which the rise of the seawater in the ground can be monitored. Being proactive is likely to be the best defense, he said.

“We want to raise awareness before contaminants become mobilized – not after the toothpaste is already out of the tube,” Hagedorn said.

About the CSU and the Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology

The California State University is the largest system of four-year higher education in the country, with 23 campuses, nearly 56,000 faculty and staff members, and over 485,000 students. Created in 1960, the mission of the CSU is to provide high-quality, affordable education to meet the ever-changing needs of California. One in every 20 Americans holding a college degree is a graduate of the CSU and our alumni are 3.9 million strong.

The CSU Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology (COAST) promotes research and education that advance our knowledge of marine and coastal systems. COAST has over 500 members from throughout the CSU working to inform solutions for ocean and coastal issues at multiple scales.

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.