1. What we monitor doesn’t get you sick–but does identify the presence of pathogens.

The fecal indicator bacteria that we monitor are not pathogenic themselves, but they often coincide with disease causing pathogens such as Vibrio, Salmonella, and Staphylococcal (a.ka. staph). Such as in the famous case of the 71-year old surfer who contracted a staph infection after surfing in the rain. Pathogens themselves are not tested because it is often infeasible due to cost and/or a time-consuming laboratory procedure.

2. Sources of indicator bacteria and corresponding pathogens range from your toilet to your local seagull population.

Human waste is the most famous source of both indicator bacteria and pathogens of direct concern to human health. Waste gets to our waterways through runoff, overflow or seepage from septic systems, and, in the case of chlorine-resistant Cryptosporidum, treated wastewater. However, your pet’s waste, wildlife, and livestock operations are also causes of contamination.

3. The motion of the ocean and the motion of a person in the ocean affect the likelihood of illness.

Tides, currents, physical characteristics of the beach and other environmental conditions affect the levels of indicator bacteria and corresponding pathogens in the water. For example, if a stream runs directly into the ocean through an enclosed bay, it has a higher chance of raising contaminant levels above the health limits than a stream that passes through a sand berm and runs into an open ocean with fast moving currents. This is because the sand berm can help filter the microbes and the increased movement helps disperse bacteria.

Your own interaction with the water also affects the likelihood of getting sick. Exposure to pathogens can happen through ingestion, inhalation, or direct contact with contaminated water. Generally, you are more likely to get sick through activities like surfing, where you are likely to have your whole body immersed in water and swallow water, than through simply wading near the beach.

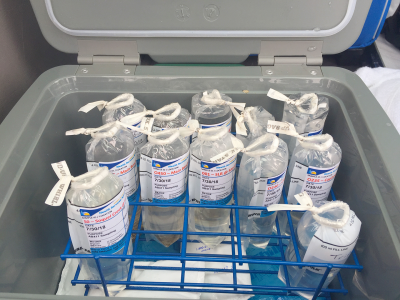

4. Fecal indicator bacteria testing isn’t perfect – but it’s a step in the right direction.

Testing for fecal indicator bacteria is a good surrogate for pathogens in waterways and can help determine if a waterbody is chronically polluted and if entities discharging bacteria into waterways are complying with regulations. But it is too slow to use for rapid response monitoring. Traditional testing methods take about 48 hours, and by the time the test result is available, the bacteria may be dead or dispersed and the threat to public health may already gone. New genetic testing methods can give results within the day, and computer models which aim to show water quality in real time are being developed. For full rundown on the strengths and weaknesses of FIB check out the U.S. EPA Technotes 9.

Thus, in this endless California summer as you don your wetsuits, bikinis, trunks, snorkels, and onesies, remember that the Water Board is taking active steps to update water quality regulations and protect the public that plays in the water. To find levels of bacteria in your play place, check out Heal the Bay’s Beach Report Card and Nowcast, the Water Board's E. coli monitoring map, or the Swim Guide.

Written by Lark Starkey