Before her John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship, Tricia Light had spent five years completing a Ph.D. at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. Her days were spent in scientific laboratories, then, or aboard research vessels. So the marble hallways of a Washington, D.C., executive office were a starkly new setting.

“It was the polar opposite of the places I’d grown used to,” Light says, reflecting on her recently completed Knauss Fellowship. But she quickly realized that the skills she’d developed as a scientist — “creativity and communication and strategic thinking,” she says, among others — were abilities that could help her thrive in this new world of policy.

The one-year Knauss Fellowship places early career professionals in federal government offices in Washington, D.C., as an opportunity to see how the kind of marine and ocean science studied in graduate school can influence law and policy. Light was one of two 2024 fellows who, having received graduate degrees from California universities, represented California Sea Grant.

Light was placed in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), which, she says, “steps in on those really complicated questions, the issues too big for any one department or agency to work on on their own.” That meant her portfolio ranged from fisheries to sea-level rise to ocean acidification to offshore energy; after years in the nit and grit of science, she was suddenly at the 30,000-foot level, seeing how policy got made. Light came to think of the year as a “sampling platter” that introduced her to all the federal agencies that work on ocean-related policy.

One of Light's major accomplishments was her work on the National Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal Research Strategy. “I was doing a lot of the coordination, bringing folks together and planning meetings, but I was also using my expertise as a scientist to think about what questions are important,” she notes. The strategy, published in November, highlighted her ability to bridge scientific expertise with policy coordination.

“There was no boring day,” Light says. “I got to talk to the smartest people about the most important and most interesting issues daily.” The year was a major confidence boost: Again and again, Light was thrust into new and challenging situations, and she always found her way through.

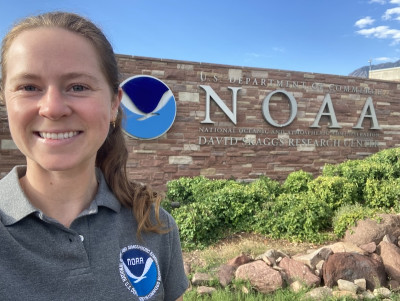

California’s other 2024 Knauss Fellow, Karlee Liddy, completed a master’s degree in coastal science and policy at the University of California, Santa Cruz. When she applied for the fellowship, Liddy was torn between serving with the executive or the legislative branch of the government. In the end, she got a bit of both: She was placed with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Congressional Affairs Team. The office works with scientists to respond to inquiries from legislators and their staff.

A major part of Liddy’s experience was visiting over 16 different congressional offices to advocate for maintaining ocean-observing instrumentation. “Continued funding for this equipment is not that flashy — it’s not the kind of thing that Congress can easily tout to constituents — but the instruments help inform the forecasts that farmers and fishers alike rely on, and we wanted to make sure that representatives understood that,” Liddy says.

The fellowship experience reshaped Liddy's career aspirations in unexpected ways. “Before the fellowship, I probably wouldn't have considered government affairs positions, but now that’s my plan,” she says. Light, too, now hopes to stay in policy work — though what that work will look like is in flux alongside the size and shape of the government.

New administrative policies are leading to job and budget cuts. But that, as Liddy notes, makes the skill of translating science and its importance to a wider audience all the more critical: We need a bridge between these worlds.

“I am a firm believer that scientists should take every and any opportunity they get to go to city council meetings, to engage as much as they can in local politics,” Liddy says. “But the flip side is true, too: we need more politicians and decision makers to work closely with experts in STEM. That way, we know our policies can be grounded in the best available science.”