Plastic is ubiquitous in our lives now — appearing in the clothes we wear, the contact lenses we place in our eyes, even in tea bags and chewing gum. On farms, too, plastic has become essential, as netting that provides shade and pipes that deliver water, among other tools.

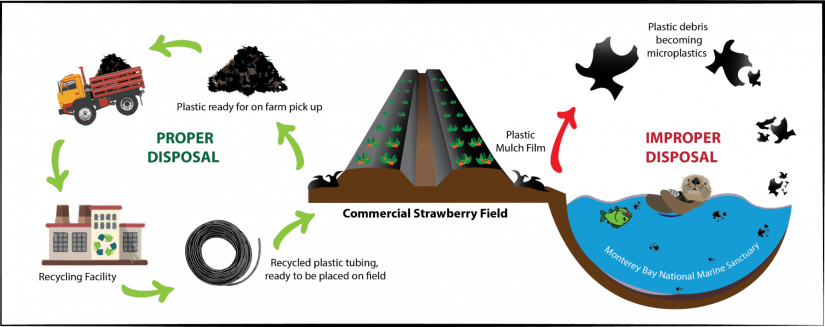

For California’s strawberry growers, for example, a thin plastic film made of polyethylene known as “plastic mulch” controls the temperature of the soil, which can extend the length of the growing season. By blocking sunlight, the mulch keeps weeds from growing, reducing the need for pesticides. By holding in water, it reduces the need for irrigation. As the agriculture community moves towards a more sustainable future, strawberry farmers have identified an opportunity: Ensure this mulch is recycled, keeping environments, and oceans especially, clean.

The result is a partnership that has brought together industry partners seeking to collaborate, rather than compete to solve this problem. Using funding from California Sea Grant, California Marine Sanctuary Foundation (CMSF) set up a partnership — including Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, Cal Poly, Andros Engineering, Flipping Iron Inc, Washington State University and strawberry growers themselves.

“We try to be solutions-oriented,” says Jazmine Mejia-Muñoz, CMSF’s water quality program coordinator. “So we wanted to work directly with the agricultural community, collaborating to find something that works.”

Strawberry farmers are eager to remove the film at the end of the growing season to prepare the field for other vegetables. Unlike the plastics used in water bottles and other consumer materials, which are often composites, the mulch is typically pure polyethylene. That homogeneity presents an opportunity: the material can be easily melted into a feedstock that can be used to create other plastics.

Even the sheer bulk of the material can be a plus. Removing it has “a really tangible, visceral impact,” says James duBois, the senior manager of environmental sustainability for Driscoll’s, a global leader in strawberry sales and a key agricultural partner on the project. “We’re pioneering a system that turns a significant waste challenge into an opportunity for circularity, proving that collaboration and creativity can tackle even the most entrenched issues in agriculture. By working with partners across industries, we’ve set a standard for what’s possible in ag plastics recycling, and we’re proud to lead the way in making a scalable impact.”

Still, there are inherent challenges to recycling this plastic: If it breaks apart during collection, that will still cause pollution. If the plastic retains too much dirt or other refuse, that will ruin its ability to serve as a feedstock. And if the mechanical collection process is too labor-intensive or expensive, the practice becomes cost-prohibitive. Thanks in part to the California Sea Grant, duBois says, a clean and functional process is now close to being cost-neutral — “close enough that we now have growers who recycle every ounce of plastic from their fields.”

One key has been finding partners who had bright ideas about how to fix the problem. Andros Engineering, for example, a specialized equipment manufacturer, had already developed a tool known as a “MEGA binder” that collects and compacts the plastic. “It creates giant rolls that weigh around 2,000 pounds,” Mejia-Muňoz explains. Flipping Iron Inc., an agricultural equipment company, is managing the collection process for interested growers.

The grant has been especially helpful in developing the next step, duBois says: “dry-washing” the rolled-up plastic. The bundles are cut apart and the pieces are passed through a rotating cylindrical sieve. As the plastic tumbles, as much as 80 percent of the dirt and other non-plastic contaminants fall out, helping clean the plastic for recycling. “Without those two processes — the collecting and the processing — we couldn’t be doing what we’re doing,” duBois says.

The funding also allowed CMSF to hold demonstrations of the process for growers in Ventura, Santa Barbara, Monterey and Santa Cruz counties. “That really helped extend awareness,” says duBois, who has been amazed by how quickly the process has caught on. Driscoll’s set internal goals for how much plastic would be recycled by 2025 — goals that felt like a stretch. “But because of these partnerships, and this funding stream, we’re now already close to meeting this goal that I thought would be just too ambitious. That’s really neat.”