Magnificent kelp forests, flowing beds of vibrant green seagrass, and enigmatic deep-sea corals are interwoven by a vibrant array of inhabitants both familiar and alien. Rich habitats that support life from the smallest microorganisms to the colossal blue whale. More than just a scenic backdrop for our coastal lives, the ocean provides over $44 billion to California’s economy—enough to fund the entire annual budget of NASA. Twice. In order to maintain the great value this system provides, a statewide network of marine protected areas (MPAs) was completed in 2012 to protect key regions of important habitat and biodiversity.

“California is so well known for all its diverse underwater ecosystems,” says Flo La Valle, postdoctoral researcher with California Sea Grant and the Southern California Coastal Ocean Observing System (SCCOOS). “The whole point of creating the MPA network was to safeguard all these important ecosystems. Now our job is to create products that will help inform how the network is working in protecting biodiversity in the context of a changing environment.”

As time progresses, regular assessment and management is crucial in order to ensure that MPAs are meeting their stated goals. Their effectiveness has often been determined by measuring the observable changes that occur after an MPA is established. Have fish stocks grown? Has biodiversity increased? The underlying assumption has been that these changes could be a sign of whether or not the MPA is meeting its goals.

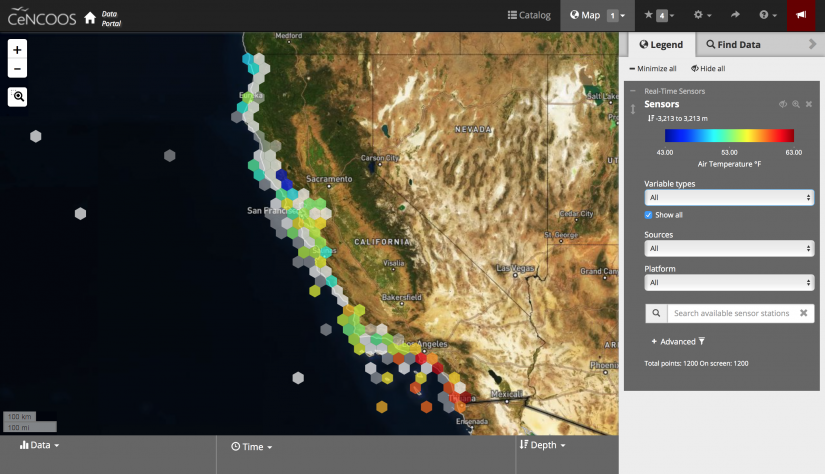

“Why does change occur in an MPA? Can you attribute a certain change specifically to MPA management, or is it due to things like El Niño or warm water conditions?” asks Henry Ruhl, director of the Central and Northern California Ocean Observing System (CeNCOOS). Whether it’s massive oceanographic shifts related to climate change or the day-to-day fluctuations in wind speed, ocean ecosystems are constantly changing. In order to determine the effectiveness of the MPA system, it’s important to weed out the changes that are due to the MPA from those which result from other environmental factors.

That’s where data science may come to the rescue. An integrative new project led by Ruhl, as part of the MPA Monitoring Program funded by the California Ocean Protection Council and California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and administered by California Sea Grant, combines a variety of biological and oceanographic data to look at these MPAs more comprehensively as part of a decadal review.

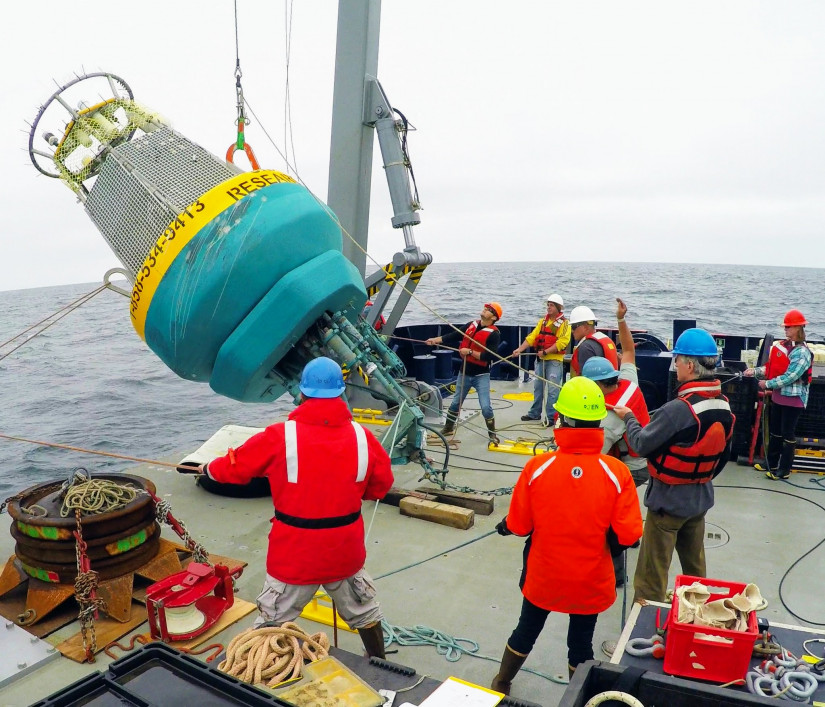

CeNCOOS and SCCOOS work as part of a collaborative partnership across the nation, utilizing a host of different tools and technologies, including buoys, sensors, animal tags, and more to collect a wealth of data about our California current ecosystems. For the first time, this project brings together a number of those datasets with ecological and economic data collected by a half-dozen other research groups to help separate the impacts of MPAs from other changes occurring in the environment—a task which is certain to prove no small endeavor.

“The MPAs were chosen because they protect very different ecosystems—a patchwork of habitats,” says La Valle. But that diversity means that each individual MPA is affected differently by certain factors, so there isn’t one simple metric that can just be applied across the state. Each MPA will need to be individually assessed, based on its own goals and local conditions, and compared with oceanographic models. After that, researchers can integrate the individual assessments to create a statewide analysis of how the whole network is performing.

“One thing we would like to do is to be able to say something more integrative across all these different ecosystems,” says Natalie Low, a postdoctoral researcher on the project at CeNCOOS.

“The integration is a really challenging and important piece. It’s really ambitious—the scale of it—with dozens of senior researchers and different datasets,” says Ruhl. “The idea here is to make a framework that is more streamlined and more robust in the longer term. By streamlining it, we are reducing the amount of human intervention we need to do every time we look at this.”

When the project is complete, the team will make this integrated dataset publicly accessible. Managers and experts in the field will be able to access the information to assess the effectiveness of current management practices and continue to improve the way our MPA network is managed throughout the state. Anyone will be able to find the information through an online portal, and the team hopes to make the knowledge more accessible and user friendly to wider audiences. Better management and more involvement in the process will help ensure the protection of these important ecosystems and the health of our oceans.

“What I find really exciting is that CeNCOOS and SCCOOS have this wealth of data,” says Low. “But being able to link that to ecological and biological responses is key to understanding how things are doing, especially under climate change. And so that is really exciting to me—we’re tapping into all these data sets that have years of investment in them, but right now are living in very separate spheres, and then putting that together to say something on a larger scale.”

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.