“We’re getting hit from all sides,” says a fisherman from Crescent City during a virtual focus group discussion. “If it isn’t the environment, it’s management.”

Over the last decade, California established an extensive network of marine protected areas (MPAs) along the coast. In hopes of providing respites where ecosystems can grow undisturbed, these MPAs set limits on activities such as fishing around the state. Researchers are now assessing how the restrictions impact marine life as well as fishing communities in seven large-scale monitoring projects funded by the California Ocean Protection Council in partnership with California Department of Fish and Wildlife and California Sea Grant.

For one team, this monitoring focuses on humans rather than fish. The project includes virtual focus groups with commercial and charter fishermen. Researchers want to know how the MPAs affect the economic and social aspects of life for fishing communities up and down the coast.

“In MPAs, what you’re managing are people — not fish or what’s on the floor of the ocean,” says Jon Bonkoski, knowledge systems program director with Ecotrust and a co-director of the team leading the human dimensions project. Bonkoski works alongside three other organizers and a larger team to gather, analyze and communicate information about the health and wellbeing of fishing communities and ports around the state.

Cheryl Chen, another co-director who works primarily on data analysis, says the project has two modes: first, pioneering a way to monitor how MPAs impact fishing communities in the long-term, and second, using existing historical data to understand research priorities and determine the most useful data to collect in the future.

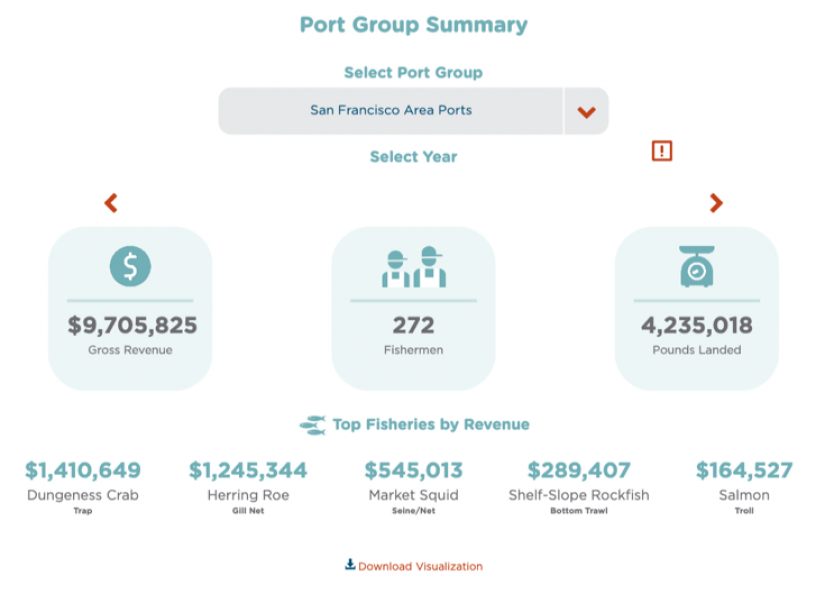

So far, the team has compiled information such as catch records, number of fishers and revenue dating back to 1992 in an interactive data explorer on the project’s website.

Chen works with Bonkoski to analyze landings data about where commercial fishing vessels operate, but she says without fine-scale digital logbooks the current data is limited. “Fish and Wildlife collects spatial fishing data, but it’s a 10 by 10 nautical mile resolution, which is too large,” she says. “A lot of these MPAs are much smaller than that.”

From figures to fishers

The team points out that catch numbers and fishing location data, while useful for statistical analyses, become more meaningful and powerful when put into the context of human stories. In order to hear voices from commercial and CPFV fisheries, Laurie Richmond, an associate professor at Humboldt State University, and her grad student, Samantha Cook, designed a series of questions and discussion points for focus groups within 24 fishing communities.

“We have around 15 questions asking fishermen to rank things about the health and well-being of their ports in relation to MPAs on a scale of one to five,” she says. “Then we ask them to rank them again after the conversation, because their views may have shifted based on the conversations they have with their peers.”

The discussions center around the sustainability, infrastructure, community and management of the ports and MPAs. The group hoped to conduct conversations in person but switched to video calls because of COVID-19.

“I was worried the technology would feel really clunky,” says Richmond. “But it’s worked really well.” She credits Kelly Sayce, another project co-director and co-founder of Strategic Earth Consulting, and colleagues Jocelyn Enevoldsen and Rachelle Fisher with getting communities involved.

“The Strategic Earth team has worked with fishermen in ports up and down the state for over a decade and built a lot of trust,” she says. “It seems that this trust has played a huge role in enabling vulnerable discussions, and I get the sense that fishermen feel that their perspectives are honored by the project team.”

The team also offers interviewees monetary compensation. “We’re not asking them to just donate their time while we’re getting paid for the project,” Richmond says. The researchers post results of focus group meetings along with key quotes and summaries for specific ports on the project website.

Reimagining management

The monitoring project’s leaders expect a wide range of responses to the wellbeing surveys. They say it’s still too early to see how MPAs affect fishing communities across the state, but one common theme has already emerged: the need for greater transparency in management. Fishing communities are typically the most impacted by the implementation of MPAs, but they consistently feel left out of the planning, monitoring and research processes.

“For the most part, fishermen are very interested in what is happening within MPAs, and there is an expressed need for clear communications on what the key findings are and how MPAs impact respective fisheries in the short and long term,” says Kelly Sayce. “Fishermen do not feel they are included in that whole conversation, and that can perpetuate a lack of trust for how resources are managed.”

The idea has persisted since the first focus group in Crescent City, where one fisherman said, “[managers] need to do a much better job of making especially fishermen, but entire communities, aware of what they’re doing.” The project team hopes that highlighting the voices of fishing communities and the challenges they face will lead to more integrative leadership at the state level.

“Ten years from now, we don’t want to come back to them and have the same conversation,” says Bonkoski. “We’re collecting this information to organize and do something proactive.”

Laurie Richmond agrees. “Fisheries management, especially at the state scale, uses lots of ecological data to guide decision-making,” she says. “It would be exciting to see this information about wellbeing guide decision-making too.”

The team believes this adaptive management is possible if fishing communities are given a seat at the table. “How amazing might it look to have fishermen together with academic scientists, managers, Tribal leaders and conservation organizations talking in a more equitable way about how resources are managed,” muses Sayce. “If ever there was a time to reimagine what engagement looks like, I just have to believe it’s now.”

Written by Erin Malsbury, California Sea Grant/UC Santa Cruz Science Writing Intern 2020

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.