“This grant will fund a postdoc at the California Academy of Sciences,” I finally managed, hoping, but not optimistic, that I sounded like I knew what I was talking about. “Our goal is to figure out how observations made by citizen scientists, using an app called iNaturalist, can inform long-term marine protected area monitoring.”

“Cool!” the secretary interjected. I looked up. This was a cool project! I exhaled. One minute left. I could do this. This was awesome.

***

Other fellows have written, with more eloquence than I possess, about their transitions from wetsuits to business attire, about the abrupt shift from life in the field to life in a cubicle. Suffice it to say that this part of my fellowship was just as difficult for me as it was for everyone else. When I chose to pursue a career in marine science, I never expected to land in a windowless office 150 miles from the nearest kelp forest. (I also didn’t anticipate a deserved, but embarrassing email with the subject line “Appropriate office voice volume,” which arrived in my inbox a few days after I started work.) But when I was offered the opportunity to spend a year as a California Sea Grant State Fellow at the California Ocean Protection Council (OPC), I couldn’t turn it down.

OPC sits in a unique place in state government. We are the Governor’s advisor on ocean and coastal policy, and we are charged with advancing science-based solutions to complex ocean problems. In short, OPC’s mission is to bridge the gap between the scientists who study the ocean and the decisionmakers who are charged with protecting it. It is a very cool place to work.

I work in OPC’s marine protected area (MPA) program. California’s MPA network spans the state’s entire 1,200-mile coastline and consists of 124 individual MPAs with varying levels of protection. MPAs don’t look like much from shore. If it wasn’t for the “No Fishing” sign posted at the trailhead to Monastery Beach in Carmel, for example, you might never know you were in one. (Word to the wise: bring a map to the coast if you plan on going fishing.) But if you’ve dove Monastery, a state marine reserve, you know that inside those little red boxes on nautical charts, you will find some of the most lush, abundant, diverse marine communities in the world. My job is to assist in coordinating the management of California’s MPAs—a daunting task, given the size and scale of the network, not to mention the millions of Californians with a stake in our oceans.

What does MPA management look like? A stack of scientific literature from the last several decades shows that you need four things in order for MPAs to achieve conservation goals:

- sound policy,

- vigilant enforcement,

- well-designed scientific monitoring, and

- effective outreach.

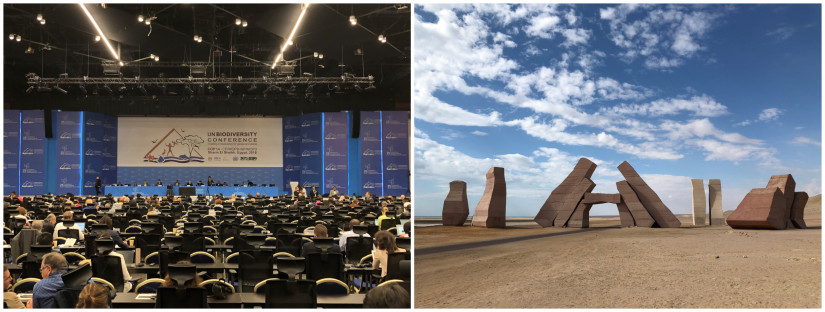

I work in each of these areas, and my day-to-day is dynamic and never boring. I manage several grants aimed at improving MPA-related outreach and education. I’m playing an integral role in developing an action plan that will guide long-term MPA monitoring and performance evaluation into the future. I’m spearheading an effort to add our MPA network to the IUCN Green List. Scientists whose papers I cited in grad school now call me directly to discuss potential collaborations. And all of this doesn’t even include the unexpected opportunities I have lucked into as a result of my fellowship work—attending the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Egypt, or sitting in the front row of the oceans plenary at the Global Climate Action Summit, just a few feet away from John Kerry, or jumping off the back of the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s research vessel to conduct wildlife surveys on scuba. Did I mention that OPC is a cool place to work?

But this year has been about more than bullet points on my resume. The most meaningful part of my California Sea Grant State Fellowship has been the fact that everyone I have interacted with in my capacity as a fellow has offered me the chance to make real contributions to important, collaborative projects. I have felt, since day one, that I have a seat at the proverbial table, and that the work I am doing means something for California’s oceans and the people who depend on them. In a world where the environment is increasingly threatened, I can’t think of a better marriage of my passions for the ocean and for scientific inquiry.

So, dear future fellow, if you are considering the California Sea Grant state fellowship, I full-throatedly offer the following advice: do it. Dive in and embrace this unique opportunity. Your fellowship year will be different from what you are used to. It will be hard. It will leave you exhausted at the end of long days. It will leave you frustrated as you navigate the byzantine system that is state government. If you are a man, you will need to learn how to tie a tie. But it will be worth it, because your work will produce tangible results for ocean conservation. Saving the planet is something that a lot of people talk about, but few actually get the chance to do. Take your seat at the table.

Written by Mike Esgro (@michaelesgro)