I have about 15,000 takeaways from my science communication-focused California Sea Grant State fellowship at the Delta Science Program. Here are just three things I’ve learned.

- The building block for positive change is not more knowledge. It is community, and community can be found anywhere. Yes, even Twitter.

I am embarrassed to admit that in my master’s program, I was a bit of a loner. I was focused on my mission to learn about bridging the science-policy divide, so I worked during class breaks and traded in potential trips down the coast to Big Sur to write my papers through the weekend. I didn’t realize that in putting blinders on, I wasn’t finding the solution. I was isolating myself and creating the type of division I was striving to remove. Now I know getting science into policy decisions isn’t about transferring information from scientists (the “experts”) to policymakers (the “non-experts”). It is about fostering an environment where people truly listen to each other.

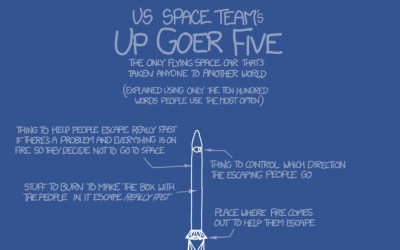

2. Scientists that want to communicate their work to a broader audience need to unlearn the writing they were taught in college.

When I first learned to write academic articles, points were deducted for using ‘I’ or ‘we’. Maybe it was the same for you. The format promoted objective science and put the research on center stage. To speak to a non-science audience, I had to learn to bite this habit.

Successful science communication isn’t adjusting words to plain English. It must transform something that was suitable in a culture with one value system (objectivity, logic, consistency) to be accepted in another culture with a different value system. That’s the ‘know your audience’ bit that you might have heard before.

- There is a science to why literally just being nice to people is a key communication strategy.

Earlier this year, I went to a conference where the keynote speaker, Emily Calandrelli, spoke on kindness and empathy. It was an ‘aha’ moment for me! Kindness has always been important to me, so it was exciting to learn it’s also scientifically more effective. TV recycles the narrative of the jerky smart scientist (Rick on Rick and Morty, Sheldon Cooper on Big Bang Theory). There is this belief that the smarter you are, the more entitled to unkindness you are. But when you are condescending, you affect the part of a person’s brain that makes rational decisions and thinks critically, inhibiting their ability to receive and accept new information.

I’m applying these lessons daily as I write web content, attend Council meetings, plan conferences, write fact sheets and infographics, and think up new ways to connect Delta science to broader audiences. I’ll take these lessons with me on my next steps, too.

Written by Heidi Williams (@heibernator)