With 3,427 miles of tidal coastline, California is one of the states expected to be most affected by sea-level rise. California coastal communities are in the midst of planning for a future where high tides lap up against coastal homes, and storms block roads and damage businesses. According to the state’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment, released in 2018, rising seas could cause over $17 billion in damage to residential and commercial buildings by 2100. That doesn’t include damage to rail lines, roads and bridges that lie in the path of rising waters.

“It’s not just individual places that are at risk, it’s the risk of local and regional connectivity. How can you move your product from the port to the store if the road is flooded? How do you commute to your job? How to you get your kids to school if it’s unsafe? What happens if public transportation goes down and you don’t have a car?” says Brenna Mahoney, coordinator of the NOAA San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Sentinel Site Cooperative and part of the California Sea Grant Extension Program.

But while the statewide projections may be daunting, the solutions are inherently local. Each coastal community has its own unique geography, ecology, development patterns, and politics, which requires analysis and engagement at a local level, developed in concert with local policy makers.

“California is at the forefront of planning for sea-level rise and we have some really good guidance and leadership from the state. Coastal cities and counties have an amazing amount of resources available to identify where vulnerabilities are and where they will be in the future. There are major vulnerabilities to both urban areas as well as in natural and protected areas, and some important ecosystems and habitats are at risk. We need to be proactive about getting projects on the ground, that will allow natural systems to adapt as well as to protect our communities and built environment,” says Mahoney.

Two recent research projects funded by California Sea Grant help fill in the gaps, translating complex projections into local case studies and guides that policymakers are now using to plan for local impacts.

A murky future for San Mateo County marshlands

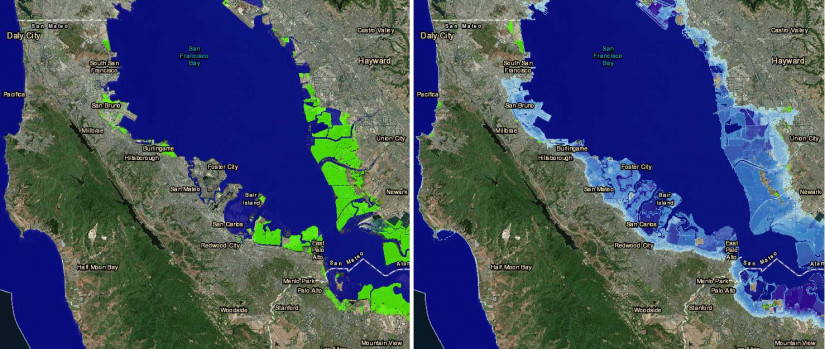

San Mateo County, south of San Francisco, is between a rock and a hard place when it comes to sea-level rise. Sandwiched between the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay, the county is home to over 700,000 people and major tech industry campuses including YouTube and Facebook.

“The bay side of San Mateo County is one of most vulnerable coastlines in the state in terms of potential impacts from sea-level rise, because of both topography—lots of low-lying areas along the shoreline—and patterns of development. The area is highly urbanized right up to the shoreline edge,” says Maya Hayden, senior ecologist at Point Blue Conservation Science, who led a recent project funded by California Sea Grant.

The county recently completed a vulnerability assessment which focused on the potential impacts of sea-level rise. Hayden’s study added to that assessment with an analysis of how sea-level rise will affect San Mateo’s marshlands. These tidal wetlands are important habitat for fish, birds, and other animals, and also provide societal benefits such as protecting shorelines from erosion, filtering pollution from water, and sequestering carbon.

Because they are constantly fed by sediment, marshes in the bay have been able to keep up with the steady, slow sea-level rise that has been taking place for centuries. But the increasing pace of sea-level rise resulting from climate change is likely to tip that balance. The question is, when?

Hayden explains, “There are two main pieces to the puzzle. The first is, how much sediment is available in different parts of the bay and how much will be available in the future? And second, how quickly are seas going to rise?”

Whether San Mateo’s marshes persist into the next century may largely depend on how quickly the world acts to address climate change, the study shows.

“Even with low sediment input, marshes will likely be able to keep pace with sea-level rise until about mid-century,” says Hayden, “But after that, the rate of sea-level rise is projected to diverge depending on which emissions pathway we are on.”

While marshes might be able to keep up with a lower rate of sea-level rise, “In the high-end ‘business as usual’ emissions pathway, which we looked at in our study, sea level is projected to rise much faster than marshes can keep pace in place. Unless we actively add sediment to marshes, or give them the space to move inland as seas rise, we are likely to lose them and all of the benefits that they provide.” More information about the project, including a detailed technical report, can be found at www.pointblue.org/SanMateoWetlands.

Planning for uncertainty in Monterey

The most recent sea-level rise projections for California use a new probability-based approach, showing not only one number for projected sea-level rise in a given emissions scenario, but a range showing the likelihood of different possible rates of sea-level rise and thus of impacts.

Another recent study funded by California Sea Grant helps make this uncertainty accessible, to provide local policy makers with an understanding of risks and a framework to analyze costs and benefits of adaptation actions given an uncertain future.

Charles Colgan and colleagues at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey developed a new model that allows planners to view possible futures, understand how likely different cases are and plan for them by providing a more complete understanding of the costs and benefits of different options. The tool can give policymakers a better understanding of costs of action—and of inaction.

“From the scenarios and probabilities, we’ve developed a simulation that can forecast thousands of possible futures in the computer and estimate the probable effects of sea-level rise and responses to it over many different iterations of the future. We come away with not what will happen but probabilities. We’re trying to help California planners get directly to the science that underlies the Coastal Commission and Ocean Protection Council recommendations.”

Because the model integrates sea-level rise projections, potential solutions, and cost-benefit analysis, it allows policymakers to ask “what if” questions about the future. In Monterey, Colgan says, they asked questions like, “What if we do things sooner rather than later? What if economic growth or population growth in region isn’t what we expect?”

For the City of Monterey, the researchers found that while most projections show the biggest impacts of sea-level rise will come after the year 2050, there is no economic benefit in waiting to take adaptation measures.

Colgan says, “In the Monterey case, our analysis showed that it is better to start sooner rather than later. If you wait until 2050 to take adaptation measures, there’s almost zero probability that you’ll get an economic benefit from waiting.”

Plan for the worst, hope for the best

While planning for sea-level rise is a daunting task, projects like these can help show the way for other communities facing the same issues. Mahoney, whose role as Sentinel Site Coordinator is to help coordinate projects, from research to education and outreach materials on sea level rise efforts for the Bay Area, says that projects like these could prove useful for other communities working to plan for sea-level rise, but that more coordination is needed.

She says, “Cities and counties are working together, but they need more capacity – there are gaps and information needs and a need to coordinate lessons learned from project successes and challenges at all levels to ensure a more resilient, regional Bay Area.”

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.