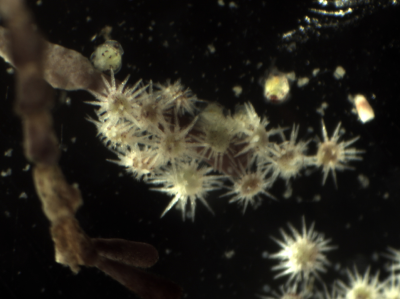

On an island in northern Washington, a scientist places a drop of seawater on a microscope slide. His ears no longer register the sounds of trickling seawater that fill the room, and his attention remains unbroken as he expertly brings the specimen into focus. What he finally sees utterly delights him. It is a larva of the biggest sea star species on the planet, the sunflower star, Pycnopodia helianthoides, whose ecological role at this tiny life stage may hold some of the answers to the most pressing questions surrounding northern California’s kelp forest crisis.

Starting in 2014, bull kelp forests in northern California’s Sonoma and Mendocino counties declined dramatically, and since then, estimates of kelp canopy area through 2021 have remained at least 90% below the historical average. Vast swaths of coastline once overflowing with bull kelp forests became overrun with purple sea urchins. The decline is thought largely to be the result of two main factors: a marine heatwave that directly reduced cold water loving kelp, and sea star wasting disease, which killed millions of sea stars along the west coast.

Among the most hard-hit was the sunflower star, historically one of the most abundant sea star species on the Pacific coast. Sunflower stars are the largest sea star species on the planet, having up to 24 arms and a diameter of four feet. They are predators that eat a variety of sea creatures including purple sea urchins. Due to this direct predation and the fear response they likely invoke in urchins, the loss of sunflower stars is cited as a major factor in the purple urchin explosion and bull kelp loss.

In response to this crisis, coastal managers, researchers, nonprofits, and community groups bounded into action, launching dozens of projects to characterize kelp losses, identify and fill information gaps, and begin restoration projects. In 2020, California Sea Grant and the California Ocean Protection Council, in partnership with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, funded six research projects as part of their $2.1 million Kelp Recovery Research Program.

One of these projects, A Multi-pronged Approach to Kelp Recovery Along California’s North Coast, is taking a broad ecological approach to understanding kelp forest degradation by considering the major organisms involved, including two important bull kelp forest players: purple urchins and sunflower stars. Dr. Jason Hodin, a Senior Research Scientist at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Labs, leads research on the interactions between the kelp-eating urchins and their sunflower star predators. Purple urchins and sunflower stars are often the focus of restoration practitioners, but the truth is that very little is known about the details of their relationship, especially in their tiny juvenile stages.

Unlike sea otters, adult sunflower stars do not eat enough urchins to noticeably reduce the population.

“Otters eat urchins like they’re dipping into a candy bowl,” explained Hodin. “But [adult] sunflower stars eat one or two per day.”

However, while raising them in his lab, Hodin’s team found that juvenile sunflower stars can eat seven or eight juvenile purple urchins per day and seem to prefer them over other foods.

“Now we are getting up into numbers where sunflower stars could be having some direct top-down control,” said Hodin.

These results will be used to inform his team’s ecological models on kelp forest community dynamics.

Hodin, an invertebrate developmental biologist who delights in the little things in life, finds a freckle of hope amid the kelp crisis by recognizing that it has presented an opportunity.

“The catastrophic kelp loss revealed how little we understand about the individual components of a functioning kelp forest, and now scientists are finally revealing information we wish we knew 20 years ago. This ‘natural experiment’ in kelp removal is giving us the opportunity to answer some basic questions not previously explored,” said Hodin.

He smiles in excitement as he spots another spikey, larval sunflower star in the microscope. Hodin hopes his work and passion for echinoderm early life stages will help uncover the full life cycles of urchins and sunflower stars and how their interactions contribute to kelp forest stability and ultimately recovery.

About California Sea Grant

NOAA’s California Sea Grant College Program funds marine research, education and outreach throughout California. Headquartered at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, California Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Commerce.