California’s kelp forests are currently facing a major threat: deforestation.

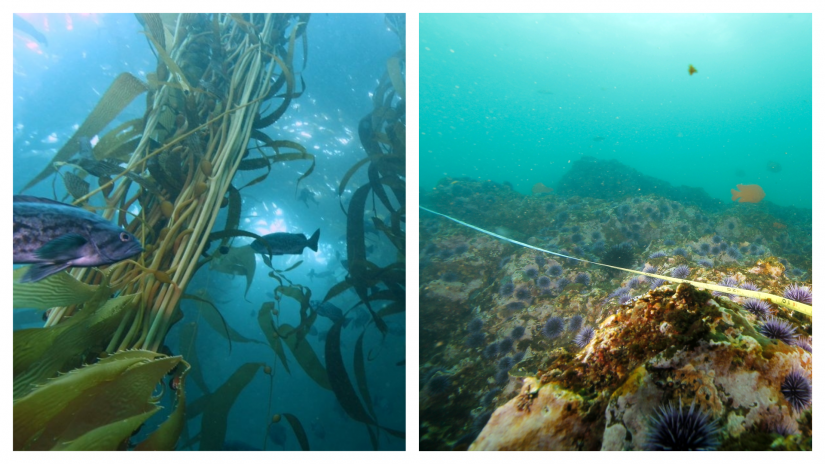

The root of this issue can be attributed to small, spiny invertebrates – purple sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus). When urchins do not face predation pressures, their populations multiply, and they devour the foundation of kelp forests. When too many urchins are present, they prevent growth of canopy forming kelp, turning a beautiful and diverse kelp forest into a wasteland – also known as an urchin barren. These barrens don’t provide any of the benefits of a kelp forest, such as harboring endangered or commercially important species, sequestering carbon, preventing shoreline erosion, and oxygen production.

It is possible for humans to reverse these barrens, by removing sea urchins and contributing to a thriving urchin fishery. While “gonad” is not a particularly appetizing word, sea urchin gonads (referred to as “roe” or “uni”) are highly desirable in the global seafood market. The problem is that urchins collected directly from the barrens are essentially worthless.

Sea urchin gonads serve as their nutrient storage, so when there is little food, gonad production decreases. One solution is roe enhancement, or the collection of wild, mature urchins of non-marketable quality and developing the roe via aquaculture. Researchers are interested in creating formulated food for the urchins specifically to enhance their roe to a market size within a few months. This framework would incentivize people to collect urchins from barrens and culture them, producing sustainable seafood and allowing kelp forests to recover.

The aquaculture class of 2019 at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories (MLML), led by California Sea Grant Extension Specialist Luke Gardner, aimed to study roe enhancement with a 10-week diet experiment on purple sea urchins. The class split the urchins that were collected from a barren, into different treatment tanks and fed them a variety of food types to better understand which diet increased gonad size the fastest.

The first step for the class was to build a culture system from the ground up. The small group of undergraduate and graduate students set up, and filled, the large tanks at the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories Aquaculture Center, then randomly assigned each tank a treatment. There were four diets available:

- an artificial diet obtained from the company Urchinomics,

- the blades of a brown algae – giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera),

- the red ogo seaweed (Gracilaria pacifica), and

- a control group that weren’t fed anything.

A dive team then collected 500 purple sea urchins from an urchin barren half a mile offshore of Pacific Grove, CA in the Monterey Bay.

The urchins were kept in their respective treatment for 10 weeks and fed every 2-5 days. Every other week, students sampled five urchins from each tank to track their growth. This involved measuring their test diameter and weighing them, then cutting them open and weighing the gonads.

Amazingly, the urchins fed the formulated Urchinomics diet grew to market size in 6 weeks! This is incredible development in a short amount of time, especially when compared to urchins that were fed red ogo seaweed (market size in 10 weeks) and giant kelp (17 weeks). In less than two months, a savvy aquaculturist could get thousands of urchins to market size and sell the roe fresh or frozen on the global market.

This class experiment gave a group of novice aquaculturists a chance to raise marine organisms and demonstrate how aquaculture can benefit nearshore ecosystems.