As someone who grew up living through yearly cycles of winter ice storms and summer heat waves in eastern Washington state, I had always viewed California’s climate as mild and stable. But with the emerging drought the past 5 years, and my new appreciation of the unpredictable sources of California’s water resources through my fellowship, I have come to realize just how off-base my initial assessment was.

We all know the basic water cycle: following the accumulation of fall and winter snow in the mountains, the resultant runoff, if unimpaired, flows into streams and ultimately the ocean the next spring and summer. Although these processes occur every year in California, the magnitude and timing of each can be extremely variable. For example, California has the highest temporal variability in precipitation for the country, because most of the annual precipitation comes from only a few storms. These few storms can make the difference between a very wet and a very dry year.

We all know the basic water cycle: following the accumulation of fall and winter snow in the mountains, the resultant runoff, if unimpaired, flows into streams and ultimately the ocean the next spring and summer. Although these processes occur every year in California, the magnitude and timing of each can be extremely variable. For example, California has the highest temporal variability in precipitation for the country, because most of the annual precipitation comes from only a few storms. These few storms can make the difference between a very wet and a very dry year.

The "water year" is a hydrological designation, running from October 1st through the following September 30th that captures the total measured precipitation over the water cycle, which managers can use to make decisions about water releases and allocations.

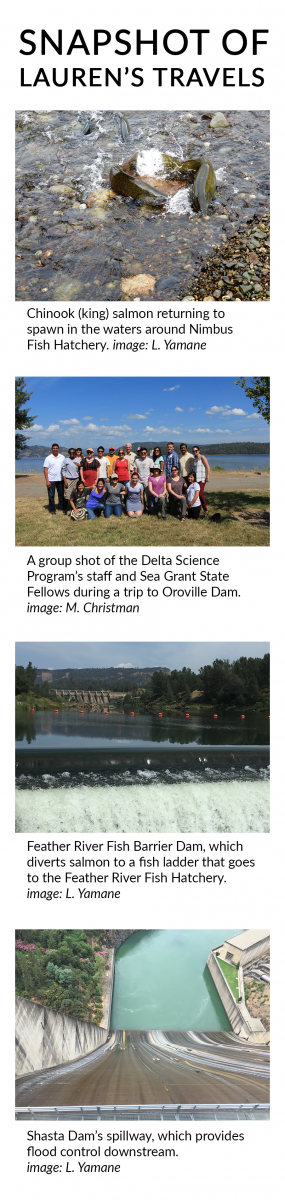

As a CA Sea Grant State Fellow in the Delta Science Program, my days are shaped by where we are within the water year, the amount of water resources available, and the timing of water flows among water users and ecosystems within the Central Valley. While not aligned with the California’s hydrologic water year, my personal “water year” experience as a Fellow has been equally dynamic and unpredictable. For example, since starting in April, I have:

- Reported on rapid rates of snowpack melt this past spring for “By the Numbers”, a monthly item to inform the Delta Stewardship Council about relevant water resource levels and wildlife survey estimates,

- Helped summarize efforts to model cold water availability for management of Winter-run Chinook salmon,

- Participated in interagency discussions with water operators and scientists regarding the movement of Delta Smelt through the Sacramento-San Joaquin watershed, and

- Gathered information related to hatchery effects on natural-origin salmon populations and their implications for recommendations in the Delta Plan (stay tuned for the white paper!).

Although I’ll be sad to leave, I am grateful to have had this opportunity. I have learned a lot about the very complex water management system in California. Thanks to the help of many great mentors at the Delta Stewardship Council, I have engaged in policy-relevant science, and I will use the perspective and communication skills I have gained throughout my career in science.

Written by Lauren Yamane