April 16, 2019

April 16, 2019

As a Berkeley native and ecologist, I love learning about historical Bay Area landscapes, which featured coastal prairie, oak woodlands, sand dunes, protected lagoons, and vast expanses of tidal marshes and mudflats. Just look at Laura Cunningham’s oil painting of the South Bay marsh landscape around 500 years ago.

From a land-based perspective it’s easy to appreciate the rich diversity of plants and animals (for example, ducks, shorebirds and tule elk pictured off in the distance) that were adapted to coastal life in and around the Bay Area.

San Francisco is also known for its prolific fisheries, such as Dungeness crab, anchovy, herring, salmon, and oysters. Yet, unless our local marine life is within view of shore—for example the annual spawn of Pacific herring in Marin—how fish and invertebrates make a living underwater can be as mysterious and awe-inspiring as construction of the Transbay Tube. One of the many notable things that distinguishes the estuary is the active concern for effects of sea level rise and other threats to the bay’s shorelines. We have the interest and resources available to take significant action to counter these threats, perhaps leading the world in this regard.

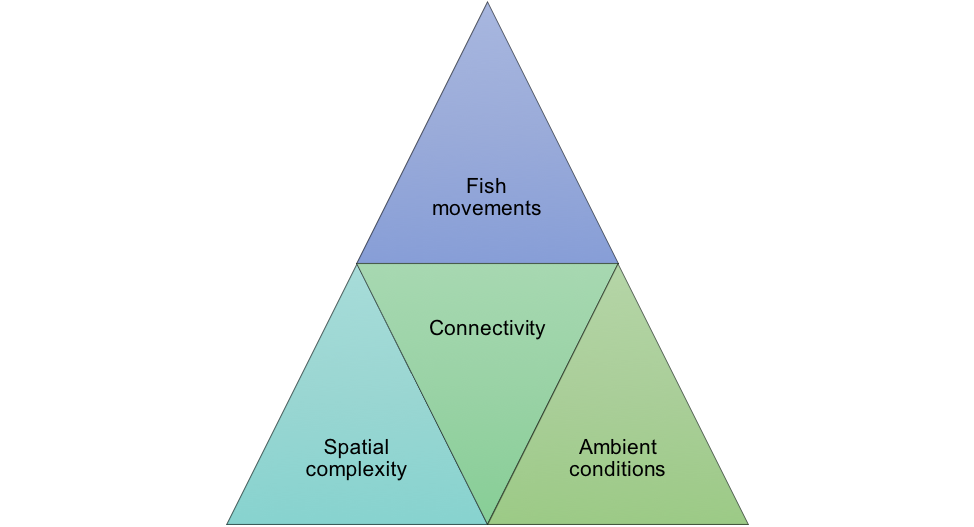

Seascape ecology can help us understand the estuary and how to manage its many habitats, which includes bays, deep and shallow channels, marshes, ponds, creeks, oyster reefs, seagrass meadows, and beaches, not to mention extensive urban development and infrastructure. It is an emerging field that applies the principles of landscape ecology to marine and estuarine environments. A researcher might ask, “How does the spatial composition, configuration and complexity of the estuary affect the way fish find food and avoid predators?”. This is the point of seascape ecology – it’s a unified framework to link spatial patterns to ecological processes.

When I first heard the term “seascape,” I dismissed its relevance to my research in the San Francisco Estuary because “sea” is equivalent to “ocean” and I don’t study the ocean. However, as I learned more about seascape ecology, I warmed up to it. I study spatial patterns of marine, estuarine and freshwater fish and invertebrates in the San Francisco Estuary, and the term “landscape” doesn’t quite capture the fact that my study species respond to changes in water depth, currents, substrate, salinity, etc., which are fundamentally different aspects of tidal environments compared to those on land.

Seascape ecology may also provide a useful way to frame some newly published research. For example, scientists recently discovered some curious things about Delta smelt, a small, critically endangered fish that typically lives in open water habitats in the upper estuary. One recent study showed that lots of larval Pacific herring showed up in the stomachs of Delta smelt that were collected near freshwater and brackish tidal marshes. Pacific herring is a forage fish that spawns in marine grasses along the bay’s shorelines and is an important part of the marine food web. A second study documented a refuge population of Delta smelt in a freshwater tidal slough next to the Sacramento River’s Yolo Bypass. These two studies link Delta smelt to diverse food and habitat resources in marine and freshwater environments, which are two seemingly disparate areas. When I read them, I started wondering to myself, what are the effects of freshwater flows and tides, and how do they interact with nearshore habitats like seagrasses, marshes, and floodplains to create food and refuge for Delta smelt? Can an integrated seascape ecology approach teach us something new about Delta smelt or other species that we don’t already know?

I propose that we use both terms—landscape and seascape—and that we embrace the spatially explicit framework to refocus our efforts on studying connectivity of habitats and populations in tidal environments that occur at the seascape-landscape boundary. Regardless of whether seascape ecology prevails as the preferred academic term, these types of questions are going to be central for studying estuaries as integrated mosaic of habitats that are connected to oceans and rivers. We clearly still have much to learn about the San Francisco Estuary and all of its marvelous underwater habitats. In this light, seascape ecology can help us develop better marine spatial planning practices – for our shorelines, for our fisheries, and for our millions of Bay Area residents.

If you’re interested in further reading, see Seascape Ecology edited by Simon Pittman, or a synopsis in this thoughtful book review.